Fat Matters

Fluid Interventions

in Anatomy

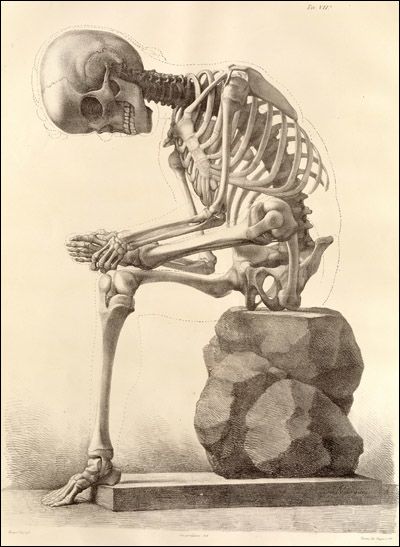

Nina Sellars

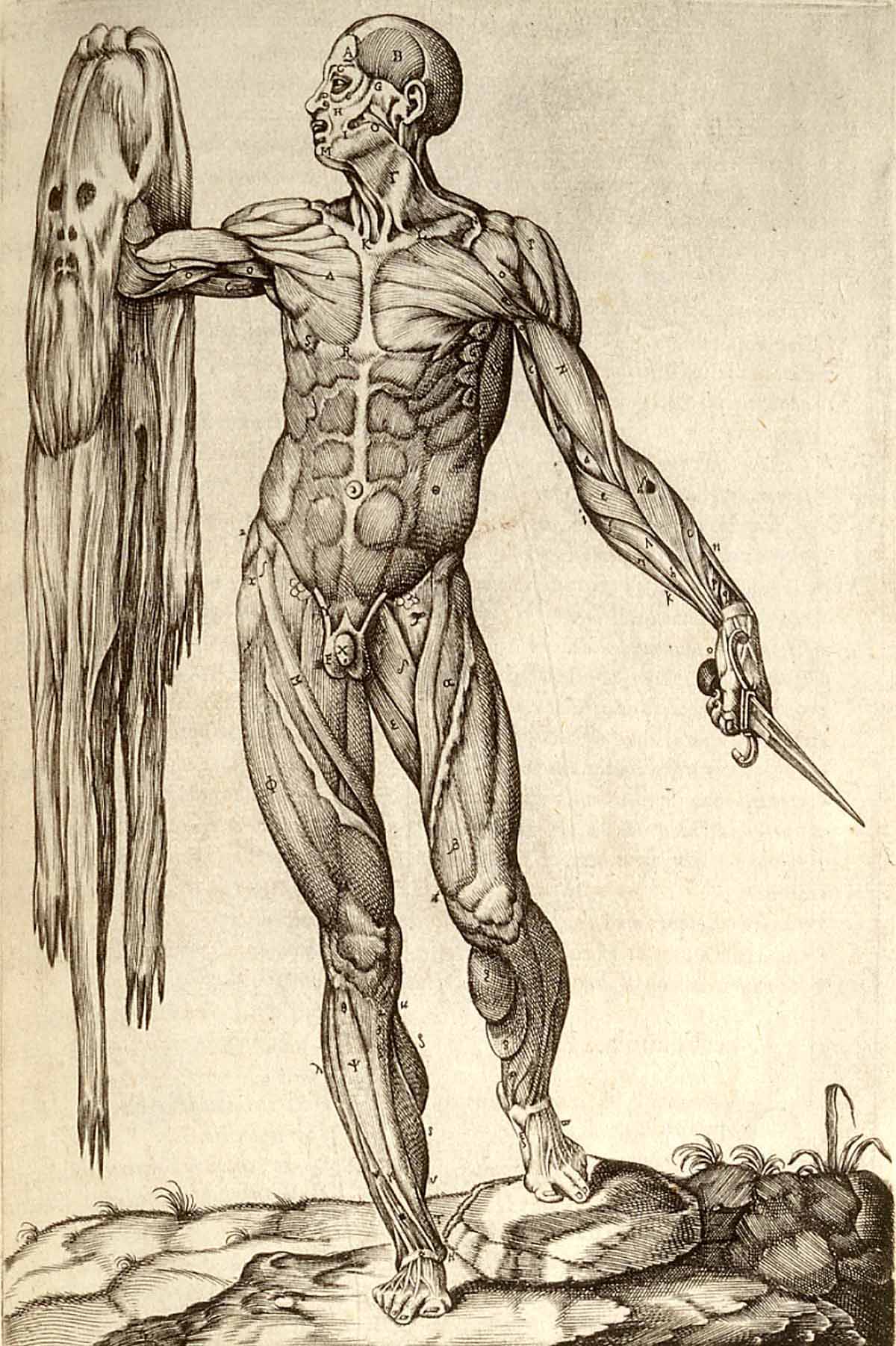

![Figure 1. Bernhard Siegfried Albinus [anatomist] Jan Wandelaar [artist]. Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani (Musculorum Tabula III), 1741. Copperplate engraving with etching. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).](./assets/organisations/pgc4dFSSO9/cRISyDWoMr/an_e-corche-_figure-_front_view-_with_left_arm_extended-_wellcome_v0008354-crop-3-1593x1035.jpeg)

Fluid Flows

Fat maintains a dynamic equilibrium.

A vital organ of homeostasis, fat regulates itself and all other tissues of the body in response to changes in the environment—both internal and external of the body. Essentially, each individual human life is enacted and maintained through body fat (aka adipose tissue) operating in constant communication with its surroundings.{{1}}{{{In this article I refer to ‘adipose tissue’ as ‘fat’ and use the terms interchangeably.}}}

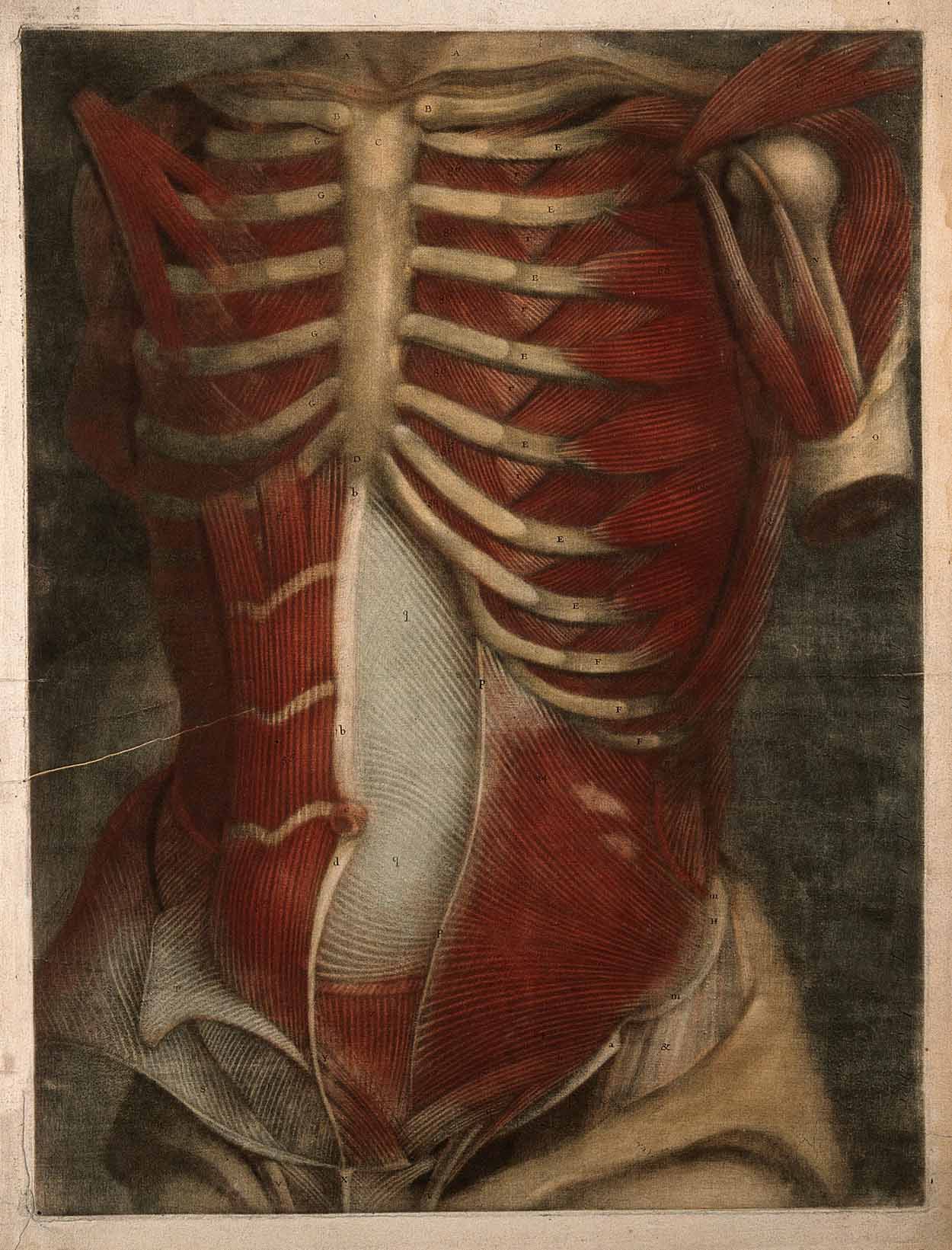

Figure 3. Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative Turin, 1837–39. Francesco Bertinatti [anatomist] and Mecco Leone [artist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Analogously, when contemplating life at a cellular level, we observe that each individual cell of the body is encapsulated in a lipid membrane—that is, a fatty acid bilayer, two molecules deep. These membranes are lively spaces of exchange, which are at once active and permeable, yet also protective, sustaining cell viability.{{2}}{{{2. Ole G. Mouritsen, Life as a Matter of Fat: The Emerging Science of Lipidomics (Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2005), 129–35.}}}

This understanding of fat as vital (i.e. both life preserving and lively, irrespective of scale) provides the broader context for the questions I raise about fat in relation to the discipline of anatomy.{{3}}{{{This point could lead into a discussion of vital materialism. Jane Bennett’s book, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, is of particular relevance here not only for her ideas on the agency of matter, but also the connections made to the theories of Deleuze and Guattari (‘assemblage’ and ‘operators’), Spinoza (‘affective bodies’), and Adorno (‘non-identity’). Moreover, Bennett’s Chapter 3, ‘Edible Matter’, includes a discussion on fat—human and non-human. See Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2010).}}}

Figure 4. Anatomie generale des visceres en situation ... Paris, 1752. Jacques Fabien Gautier D’Agoty [artist]. Wellcome Collection.

My aim is to explore the fluid nature of fat and the ways in which fat challenges, and subsequently may be seen to transform, our understanding of anatomy in the twenty-first century, taking as my entry point the relatively recent classification of adipose tissue as a complex distributed organ of the endocrine system (i.e. an organ of homeostasis).{{4}}{{{For a discussion of the classification in 1994 of adipose tissue as an organ, see Evan D. Rosen and Bruce M. Spiegelman, ‘What We Talk about When We Talk about Fat’, Cell 156, no. 1–2 (2014): 20–44. In regard to fat in traditional visions of anatomy, see Nina Sellars, ‘The Life and Death of Anatomy’, in Bridging Open Boundaries, as Part of the V&A Digital Design Weekend 2017, eds. Irini Papadimitriou, Andrew Prescott and Jon Rogers (London: Uniform Communications, 2017), 40–43. Archived online, DigiTranGlasgow, AHRC Digital Transformations, University of Glasgow.}}}

This change in status highlights that fat operates not only at the physical boundaries of our perceived internal and external worlds, but also as an outlier in our understanding of anatomy as a body of knowledge. Indeed, historically, fat rarely appears in the visual archives of anatomy (or at least rarely in a way that appears meaningful).{{5}}{{{In this text, I focus on traditional anatomy atlases and their illustrations. However, the erasure of fat can also be seen in diagnostic imaging, in which it often occurs incidentally. For example, X-ray and computerised tomography are adept at imaging denser bodily tissues, such as bone, but are relatively ineffective at recording fat. Magnetic resonance imaging provides a notable exception, as it is acutely sensitive to the detection of adipose tissue; yet, here fat is treated as an artefact of the process and removed algorithmically.}}}

A liminal matter, fat signals an opportunity to interrogate the certainty of anatomical vision and to prompt further questions not only in regard to fat and its problematic history in anatomy, but also the possible limitations of anatomy as a twenty first-century discipline.

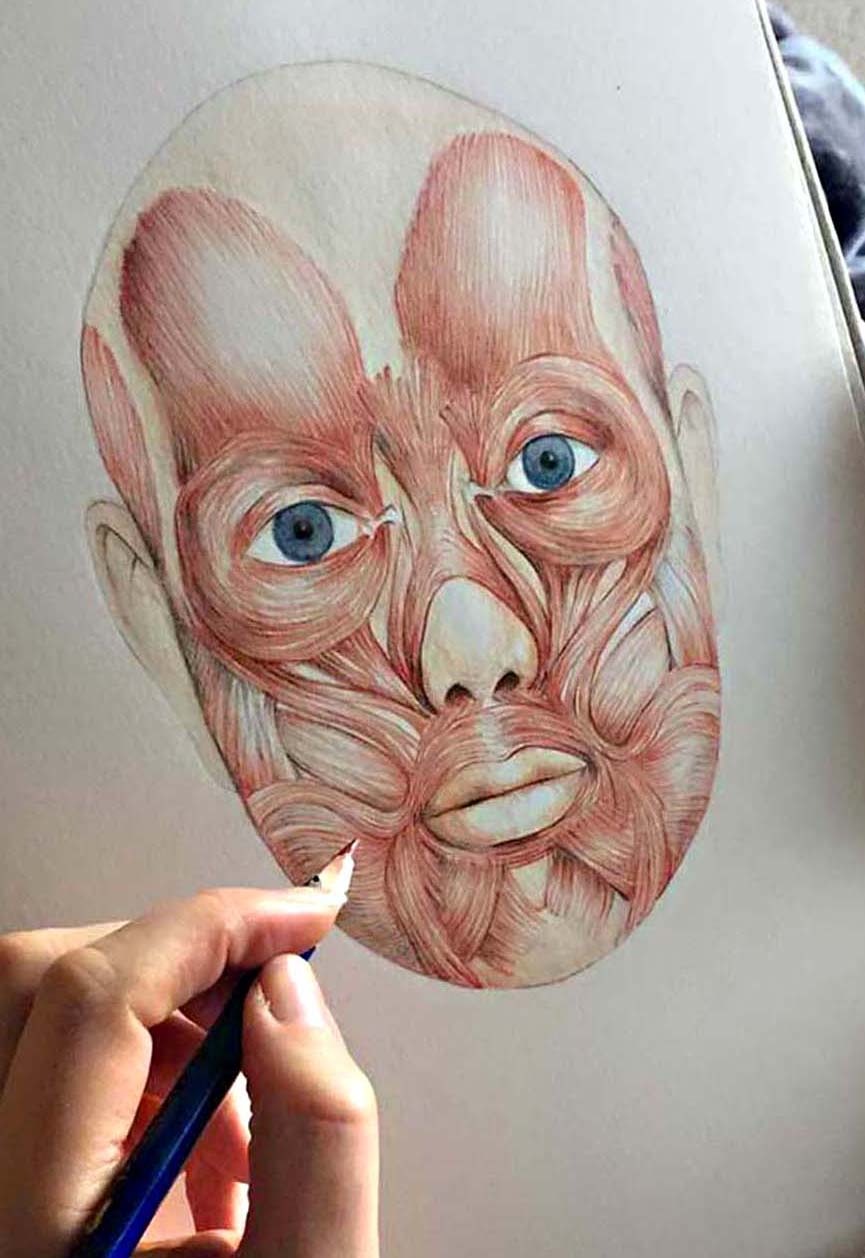

Figure 5. Superficial Muscles of the Face. Nina Sellars © 2015.

![Figure 3. Francesco Bertinatti [anatomist] Mecco Leone [artist]. Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative Turin, 1837-39. Lithograph. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Public Domain.](./assets/kS5iSBOk8G/iii-a-12-400x547.jpeg)

Figure 3. Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative Turin, 1837–39. Francesco Bertinatti [anatomist] and Mecco Leone [artist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Figure 3. Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative Turin, 1837–39. Francesco Bertinatti [anatomist] and Mecco Leone [artist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

![Figure 4. Jacques Fabien Gautier D’Agoty [artist]. Anatomie generale des visceres en situation... Paris, 1752. Plate 2, hand coloured mezzotint. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)..](./assets/1hqhpIJAoL/j-f-gautier-d-agoty-muscles-of-the-thorax-1250x1641.jpeg)

Figure 4. Anatomie generale des visceres en situation ... Paris, 1752. Jacques Fabien Gautier D’Agoty [artist]. Wellcome Collection.

Figure 4. Anatomie generale des visceres en situation ... Paris, 1752. Jacques Fabien Gautier D’Agoty [artist]. Wellcome Collection.

![Figure 5. Nina Sellars [artist]. Superficial muscles of the face, 2015. Pencil on paper. Nina Sellars © 2015.](./assets/HaKhYzRR2c/anatomical-head-2015-nsellars-h-865x1258.jpeg)

Figure 5. Superficial Muscles of the Face. Nina Sellars © 2015.

Figure 5. Superficial Muscles of the Face. Nina Sellars © 2015.

As a visual artist and former body dissector, my view of fat draws on my knowledge of anatomy and its history of visualisation, and on my practical hands-on experience of dissecting human bodies for medical display and as a maker of anatomical images.{{6}}{{{I was a dissector and anatomical illustrator at the University of Western Australia (UWA); a lecturer of anatomy for fine arts and medical and physiotherapy students at Monash University, Melbourne; and a research fellow at the Alternate Anatomies Lab (robotics and art research group), Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia.}}}

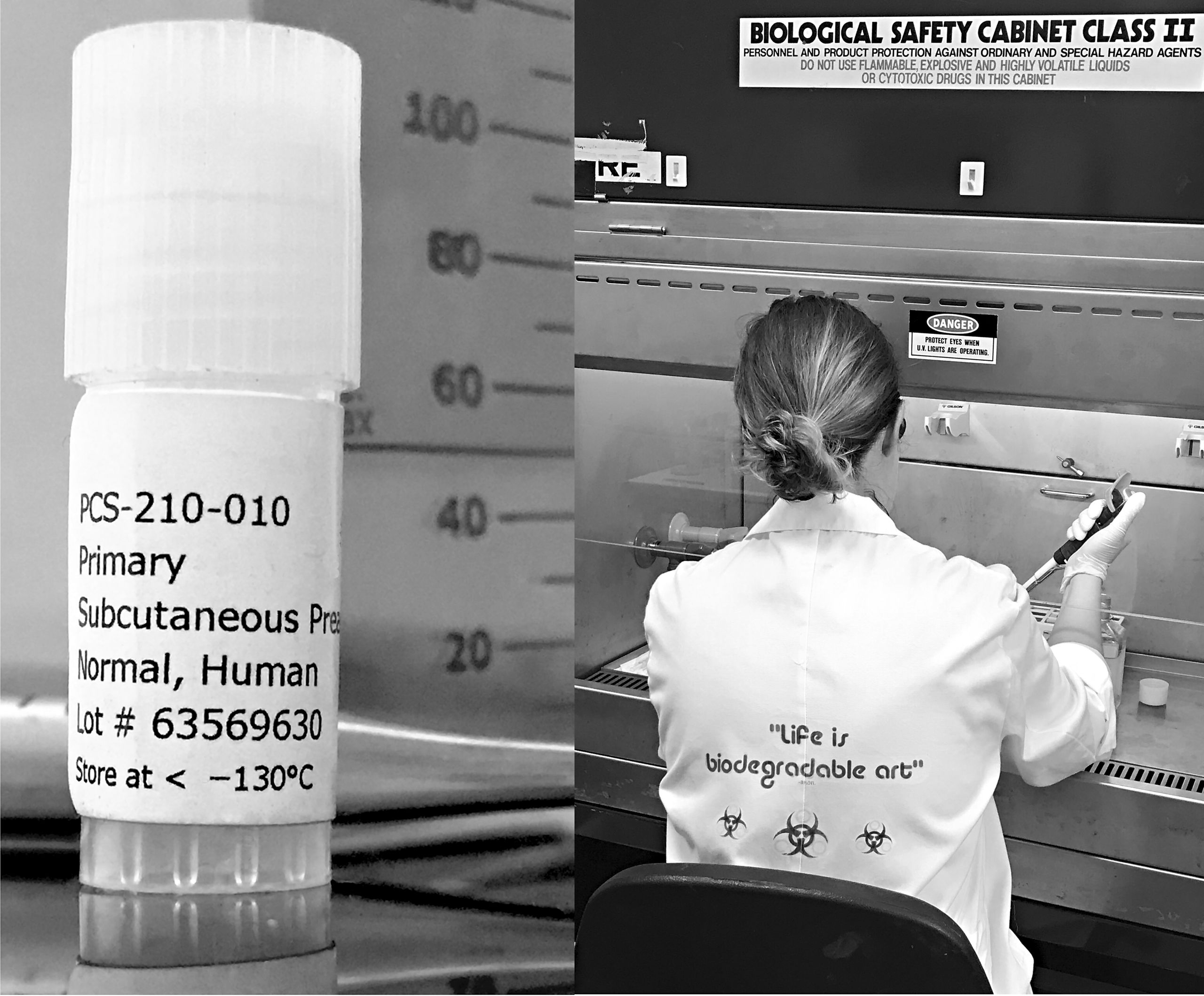

In my contemporary lab-based biological arts practice, I work with human adipose tissue culture (fat living and growing in vitro, which provides me with an environment in which I can microscopically observe human fat living ex vivo).{{7}}{{{This practice-led research has been conducted at SymbioticA, the Centre of Excellence in Biological Arts, UWA. Funding for the research was provided by the Australia Council, with further in kind support from SymbioticA. Advice on adipose tissue culture techniques was given by my mentors, J. William Futrell and Ramón Llull (International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science). My research in adipose tissue supports an ongoing series of artworks, which I present as thoughtful (fat) interventions in the historical archives of anatomy—in its museum collections and compendia. My aim is to question the cultural and scientific implications of the relative absence of fat in the history of anatomy and the significance for contemporary discourses about the human, non-human and post-human.}}} An example of my artwork is Sentinels, 2018.{{8}}{{{Sentinels was created while I was artist in residence at SymbioticA, UWA, and the Solid-State Spectroscopy Group, Laser Physics Centre, The Australian National University. The Sentinels installation contains human preadipocytes (i.e. precursor fat cells) living and growing in a semi-synthetic hydrogel (GelMA). The GelMA, and instruction for its use, was generously provided by Dr Christoph Meinert, Centre in Regenerative Medicine, Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology. Assistance with artwork production was provided at SymbioticA by Mike Bianco, Oron Catts, Callum Siegmund, Nathan Thompson and Dr Ionat Zurr, and at ANU by Matthew Berrington, Craig MacLeod and Professor Matthew J. Sellars. A documentary on the making of Sentinels, produced by Blue Forest Media, is available on ABC iview: Art Bites: Biogenesis—Sentinels. See also Nina Sellars, ‘Sentinels’, in Unhallowed Arts, eds. Laetitia Wilson, Oron Catts and Eugenio Viola (Perth: UWA Publishing, 2018), 100–03.}}}

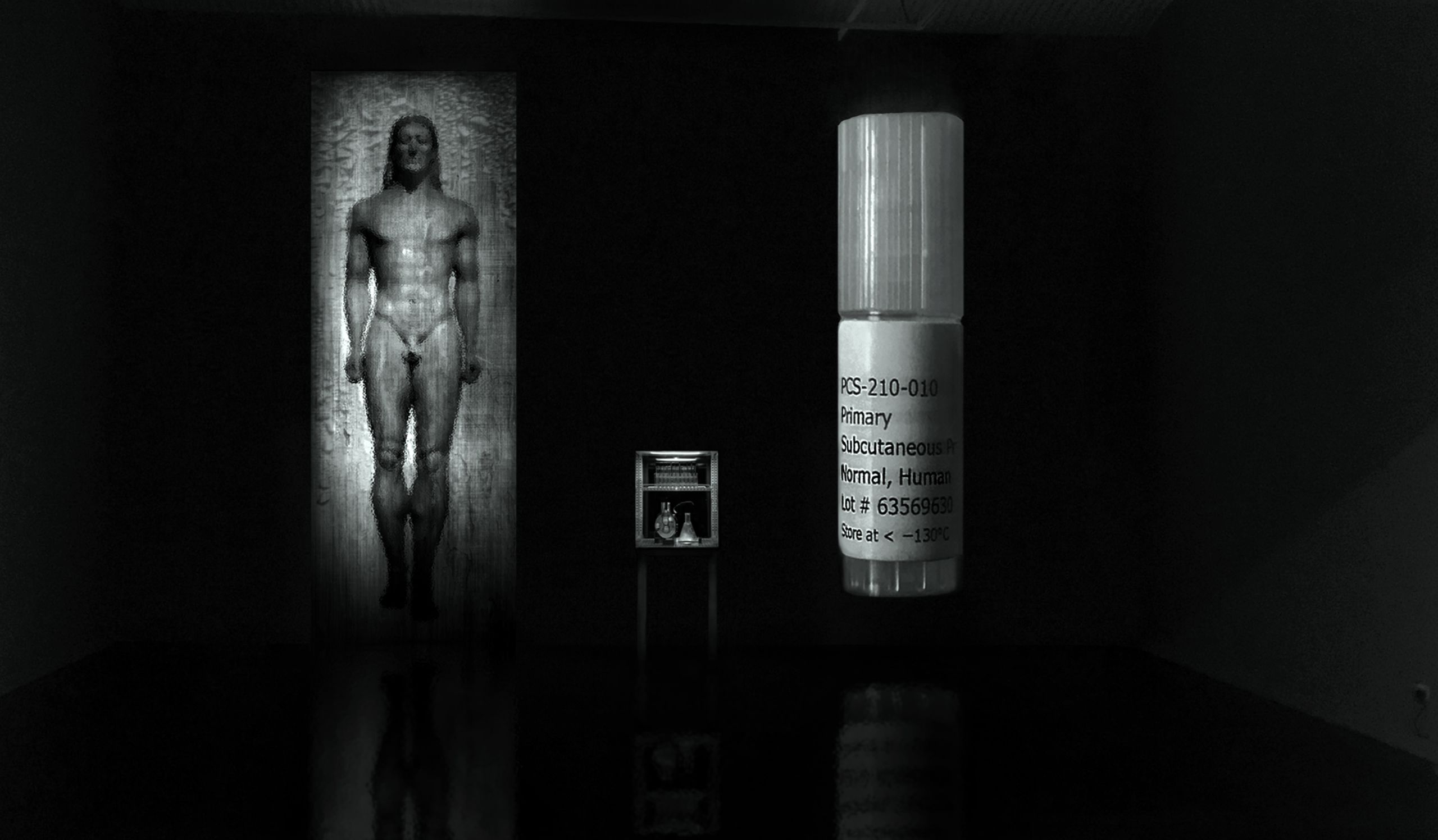

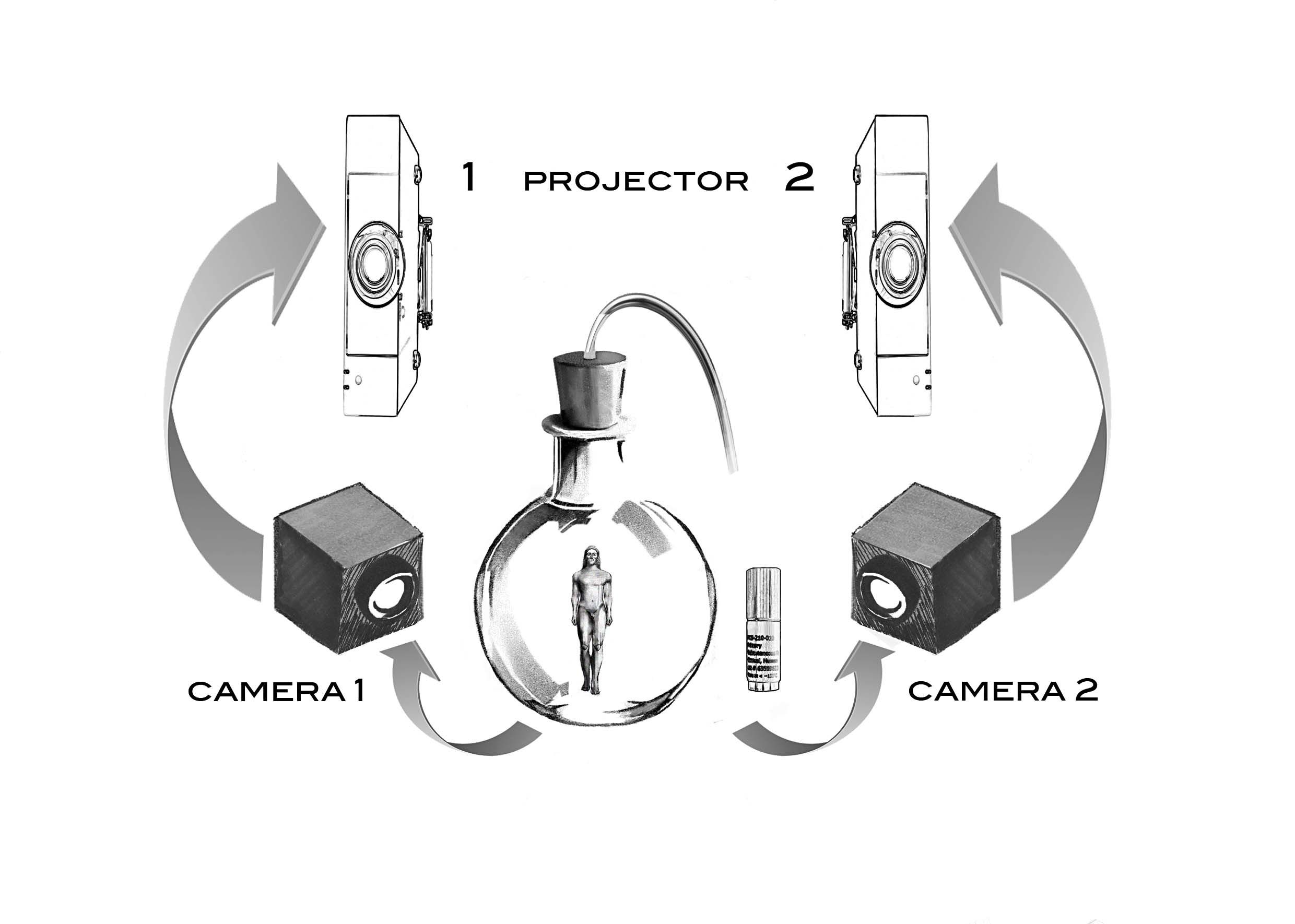

Figure 6. Sentinels (artist's visualisation of biological/new media art installation—made prior to its construction). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 6. Sentinels (artist's visualisation of biological/new media art installation—made prior to its construction). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 7. Sentinels (diagram indicating the real-time imaging relay of the two mini high definition cameras, mounted on the exterior of incubator). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 7. Sentinels (diagram indicating the real-time imaging relay of the two mini high definition cameras, mounted on the exterior of incubator). Nina Sellars © 2018.

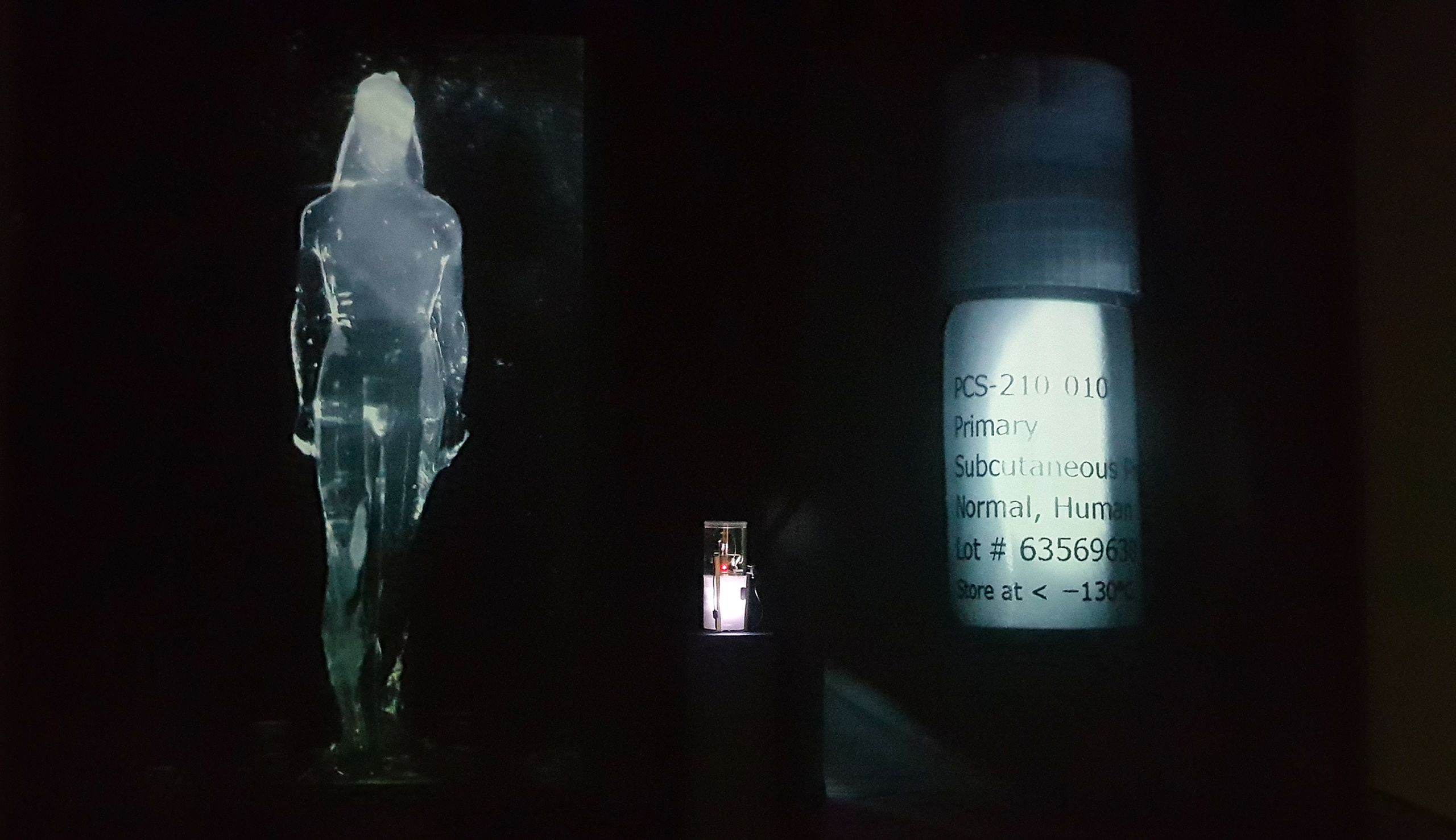

Figure 8. Sentinels (documentation of installation at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Australia, for the exhibition, HyperPrometheus: The Legacy of Frankenstein). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 8. Sentinels (documentation of installation at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Australia, for the exhibition, HyperPrometheus: The Legacy of Frankenstein). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 9. Sentinels (PICA installation detail—living human preadipocyte cells embedded in a drip-fed hydrogel kouros). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 9. Sentinels (PICA installation detail—living human preadipocyte cells embedded in a drip-fed hydrogel kouros). Nina Sellars © 2018.

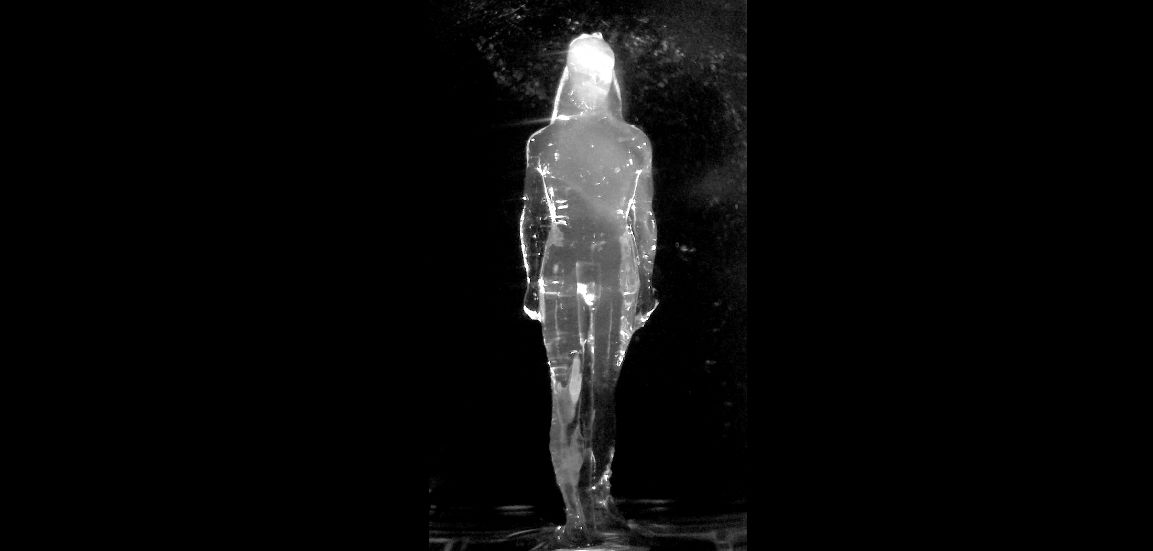

Figure 10. Sentinels (hydrogel kouros test figure: the intended host for the tissue-cultured human preadipocyte cells). Nina Sellars. Photograph courtesy of Mike Bianco © 2018.

Figure 10. Sentinels (hydrogel kouros test figure: the intended host for the tissue-cultured human preadipocyte cells). Nina Sellars. Photograph courtesy of Mike Bianco © 2018.

Although fat fulfils the contemporary criteria of an organ at a cellular level, it challenges the traditional conventions of anatomy that inform our understanding of the classification.{{9}}{{{The definition of what constitutes an organ expands under the microscopic study of living tissue. At a cellular level, an organ is considered to be a structured collection of cells that are formed from two or more tissue types that cooperatively perform a particular function.}}} Most notably, fat appears to belong to an altogether different ontological order than all other internal organs (which, in turn, can lead us to question its inclusion in this category).{{10}}{{{With the discovery in the 1990s of the first adipose-secreted hormone, leptin, endocrinologists classified fat as a complex distributed ‘organ’ of the endocrine system. The reframing of fat as a dynamic organ of homeostasis, with the capacity to regulate other body tissues by synthesising its own chemicals and releasing them into the bloodstream, countered the view of fat as a simple inert matter. For an informed discussion of fat in the history of the life sciences, see Caroline M. Pond, The Fats of Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).}}}

When we mentally picture organs, we tend to imagine the classical illustrations of anatomy atlases that depict organs as clearly delineated bounded volumes. Yet, the fluid-like quality of fat highlights its inherent contrast to this ideal. Fluids flow. Anatomy structures. That is to say, anatomy is a practice that organ-ises the flesh.

Figure 11. Nina Sellars viewing Sentinels, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2018. Footage courtesy of Blue Forest Media © 2019.

Figure 11. Nina Sellars viewing Sentinels, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2018. Footage courtesy of Blue Forest Media © 2019.

Anatomy Cuts

Historically, anatomy is a discipline informed by a series of cuts. At its etymological origins in ancient Greek, the word anatomy literally means to cut the body asunder (late Latin, anatomia, from the Greek, ana, meaning ‘up’ and tomia, meaning ‘cutting’ from temnein ‘to cut’).{{11}}{{{Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed., s.v. ‘anatomy’.}}} This makes anatomy directly related to the act of dissection.

It also places the term in a particular understanding of knowledge, since intellect in ancient Greece was structured around notions of visualisation and the word for knowledge (eidenai) was considered to signify ‘the state of having seen’.{{12}}{{{Bruno Snell, The Discovery of the Mind: The Greek Origins of European Thought, trans. T. G. Rosenmeyer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953), 146. See also, Shigehisa Kuriyama’s discussion of Snell’s reference to the word noein. Shigehisa Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body: And the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (New York: Zone Books, 1999), 120–21.}}} But ‘the state of having seen’ also involved an act of seeing beyond that required the intellect to visualise perceived ideals of form immanent in the structures of the body.

Figure 13. Anatomia del corpo humano … Rome, 1559. Juan Valverde de Amusco [anatomist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Figure 13. Anatomia del corpo humano … Rome, 1559. Juan Valverde de Amusco [anatomist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

In the sixteenth century, the Renaissance invention of perspective allowed for the plastic illustration of modern anatomy and enabled the body to be depicted as existing within a three-dimensional matrix. To the Renaissance observer, it would have seemed as though this idealised body could be visually opened up and entered into with the eye, exclusively. Here, the ancients’ notion of seeing beyond, which also seemed to imply seeing beyond fat and skin, became the act of unseeing any matter that obscured the perceived ideal forms.

This vision of the body appears naturalised in contemporary society, and increasingly represents the who and what of our being. Medical historian Shigehisa Kuriyama insightfully notes that ‘anatomy eventually became so basic to the Western conception of the body that it assumed an aura of inevitability’.{{13}}{{{Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body, 117.}}}

I suggest that the shift in the understanding of anatomy as an action (i.e. the cut of dissection) to a state (which represents the who and what of our being) occurred with the advent of imaging. In effect, we can think of the act of mediation as momentarily stabilising our idealised concepts of anatomy.{{14}}{{{Here, I am moving towards an idea expressed by media theorists, Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska, in their collaborative text, Life After New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012). Kember and Zylinska offer a way of understanding our experience of life, considered as a ‘being in’ and a ‘becoming with’ our technological world. In the text, they explore the ways in which we make ‘cuts’ (i.e. the acts of mediation) that momentarily stabilise the world ‘into media, agents, relations and networks’.}}} In this way, the cut of anatomy can be considered a twofold act: the physical action of cutting the body asunder as well as the visual cut of image-making that carves out a particular representation of the body. These images then circulate in broader society.

![Figure 14. Henry Gray [anatomist] Henry Vandyke Carter [artist]. Thoracic spine anatomy, Gray's anatomy textbook (pg. 219), 1858. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Public Domain.](./assets/noGYdA5dru/grays-posterior-torso-900x1361.jpeg)

Figure 14. Thoracic Spine Anatomy, Gray's anatomy textbook (p. 219), 1858. Henry Gray [anatomist] and Henry Vandyke Carter [artist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Figure 14. Thoracic Spine Anatomy, Gray's anatomy textbook (p. 219), 1858. Henry Gray [anatomist] and Henry Vandyke Carter [artist]. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Perhaps this explains why, in our era, there are no chapters dedicated to fat (aka adipose tissue) in any standard compendia of anatomy, nor is there a clearly defined branch of medicine dedicated to its study; the field of ‘adipology’ does not yet exist. Even illustrations in classical anatomy atlases, for instance in Gray’s Anatomy, which is currently in its 41st edition, are characterised by a relative absence of fat.{{15}}{{{Susan Standring, Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st ed. (London: Elsevier Limited, 2015).}}} In addition, the traditional dissection manuals, which are the how-to guides of applied anatomy, do not list fat in their charts of anatomical components.{{16}}{{{For example, Solly Baron Zuckerman, New System of Anatomy: A Dissector’s Guide and Atlas, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981).}}}

Yet, to say that fat is absent from anatomy and its visual history is not to say that fat is absent from our thoughts. Paradoxically, while fat eludes easy capture in the conventional categories of anatomy, it figures prominently in the discourses and practices of a body that is defined by anatomy.{{17}}{{{For example, in relation to healthcare, see this media release from the World Health Organization; for the harvesting of fat for adipose derived stem cell therapy in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, see Dana Jianu, Oltjon Cobani and Stefan Jianu, ‘Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine and Plastic Surgery: Perspective from Personal Practice’, in Pancreas, Kidney and Skin Regeneration: Stem Cells in Clinical Applications, ed. Phuc Van Pham (Cham: Springer, 2017), 273–88; for surgical fat grafting, see Rafi Fredman, Adam J. Katz and Charles Scott Hultman, ‘Fat Grafting for Burn, Traumatic, and Surgical Scars’, in Clinics in Plastic Surgery 44, no. 4 (2017): 781–91; and for critical discourses of fat embodiment and identity in the realm of cultural studies, see the ongoing journal publication, Fat Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Body Weight and Society, ed. Esther Rothblum.}}}

Fat Exceeds

Considering the absence of fat from the archives of anatomy, we can begin to identify its point of disappearance with the premise that fat appears in the act of ‘becoming’ anatomy, rather than in the state of ‘being’ anatomy. The making of anatomy as a body of knowledge inherently involves the purposeful act of fat’s exclusion, that is, its removal, for it is not that we do not acknowledge fat’s existence. Indeed, if we try to locate fat in terms of ‘belonging’ to sight and to be sited within the conceptual framework of anatomy, it can seem that fat belongs more with the instruments of dissection (e.g. the scalpel blade, the surgical forceps and the receptacles of collection) rather than the cadaver. Certainly, this vision is what guides the dissector’s hand.

As fat can appear somewhat indeterminate and fluid, anatomists are inclined to perceive of fat ending only where it meets the bounding surface of other organs. In the act of dissection, anatomists tend to reflexively look beyond fat in anticipation of the cut and the follow-through act of revealing. The subject of the revelation is the so-called ‘bounded volumes’ (i.e. the ideal forms of the organ-ised body) typically found in the illustrations of anatomy atlases. Seen in this way, fat presents both an ontological and epistemological challenge to anatomy, as the apparent plasticity and adaptability of fat exceeds the anatomical convention that unifies organs into objects with clearly discernible boundaries and structure. Indeed, fat’s formlessness means that it is often seen as residing ‘outside’ anatomy—lying on, over, under or around organs—as ‘obscuring matter’, where it is to be ‘removed’, ‘lifted’ or ‘cleaned away’ to reveal the anatomical ‘structures’. In many ways, fat defines the practice of anatomy by antithesis: fat is what anatomy is not.

Yet, the term ‘formlessness’ itself should not go unquestioned in this context. Is formlessness an inherent quality of the matter perceived or is it a quality that is conferred upon it by perception? Is it just a way we humans contend with situations in which we are presented with ‘simply too much information’ (i.e. formlessness exceeds the possibility of organ-isation)? Queried in this way, formlessness becomes a category for the inconceivable and the immeasurable, the thing that lies beyond the categorised. This returns us to the question of whether the challenge fat presents to anatomy is ontological or epistemological.

Our inquiry raises the broader underlying question: what exactly does it mean to lie ‘outside’ anatomy? Whether the cut is the physical cut of dissection or the visual cut of mediation, anatomy has traditionally been a science of trenchant division, the neat separation of one part from another part, one vision of the body from other visions. The study of fat, however, suggests, that we may now need a more pliant, nimbler science, an approach to the human body less intent on sharp and fixed boundaries. A more fluid anatomy.

IMAGE AND FILM CREDITS

Listed in the order in which they first appear in the essay.

Figure 1. Bernhard Siegfried Albinus [anatomist] and Jan Wandelaar [artist], Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani (Musculorum Tabula III), 1741. Copperplate engraving with etching. Wellcome Collection. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution International (CC BY 4.0).

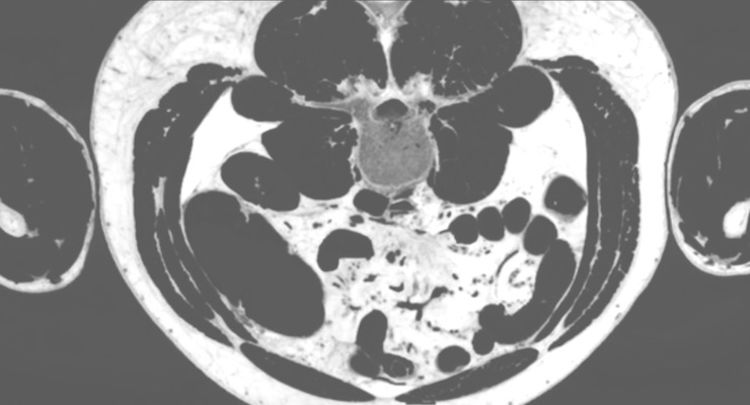

Figure 2. Visible Human Project—Axial Cryosection of the Abdomen and Upper Extremities of a Human Male, 2001. (Image altered by author to show the removal of all organs, except fat.) U.S. National Library of Medicine. Public domain.

Figure 3. Francesco Bertinatti [anatomist] and Mecco Leone [artist], Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative Turin, 1837–39. Lithograph. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Public domain.

Figure 4. Jacques Fabien Gautier D’Agoty [artist], Anatomie generale des visceres en situation ... Paris, 1752. Plate 2, hand coloured mezzotint. Wellcome Collection. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution International (CC BY 4.0).

Figure 5. Nina Sellars [artist], Superficial Muscles of the Face, 2015. Pencil on paper. Nina Sellars © 2015.

BACKGROUND IMAGE. Camille Félix Bellanger, Une Fin À l’École Pratique, 1902. Lithograph. (Copy of vintage French postcard from author's private collection.) Public domain. The Dittrick Medical History Center, Cleveland, hold an original lithographic print in their collection.

Figure 6. Nina Sellars, Sentinels (visualisation of biological/new media art installation—made prior to construction), 2017–18. The Sentinels gallery installation design incorporates a custom-built bioreactor and incubator to nurture tissue-cultured human preadipocyte (fat) cells (living, and growing, in a hydrogel kouros). Real-time video projections, which are positioned either side of the incubator to display key elements contained within. Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 7. Nina Sellars, Sentinels (diagram indicating the real-time imaging relay of the two mini high definition cameras mounted on the exterior of incubator), 2018. Camera 1—focused on the drip-fed hydrogel (GelMA) kouros (which contains living human preadipocyte cells embedded in its matrix). Camera 2—focused on the original (35 mm high) preadipocyte cell vial, acquired through the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 8. Nina Sellars, Sentinels (documentation of installation at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Australia), 2018. The installation comprises two 3.5–metre high real-time video projections: (lhs) the ‘living’ drip-fed kouros, (rhs) the original cell vial. The plinth-mounted incubator, in which both objects are contained, is located centrally, approximately 800 mm out from the wall. Nina Sellars © 2018.

BACKGROUND IMAGE. Nina Sellars working with preadipocyte tissue culture for her research and development project, Fat Culture, while artist in residence at SymbioticA, UWA. The (lhs) photograph (cell vial). Nina Sellars © 2017. The (rhs) photograph (Nina working in SymbioticA lab) courtesy of Ionat Zurr © 2017. This project was assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Figure 9. Nina Sellars, Sentinels (PICA installation detail), 2018. Living human preadipocyte cells embedded in a drip-fed hydrogel (GelMA) kouros (located in a bioreactor, inside an incubator) at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. The original cell vial, labelled ‘Primary Subcutaneous Preadipocytes, Normal, Human. Lot# 63569630. Store at < –130°C’ – appears to the right in the image. Sentinels was shown as part of the exhibition, HyperPrometheus: The Legacy of Frankenstein. Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 10. Nina Sellars, Sentinels (detail of hydrogel kouros test figure: the intended host for the tissue-cultured human preadipocyte cells. SymbioticA biological arts laboratory, UWA), 2018. Photograph courtesy of Mike Bianco © 2018.

Figure 11. Nina Sellars viewing Sentinels, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2018. Footage courtesy of Blue Forest Media © 2019. The Sentinels installation was featured in the ABC iview documentary, Art Bites: Biogenesis—Sentinels, 2019.

BACKGROUND VIDEO. Nina Sellars, Sentinels (detail of installation: showing the 3.5–metre high, real-time video wall projection of the drip-fed figure). HyperPrometheus: The Legacy of Frankenstein, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Western Australia. (The sixth-century BCE kouroi predate the arrival of anatomy; however, they were the first statues in archaic Greece to show movement. One leg is placed further forward, as if tentatively entering into this new understanding of the body. In contrast, the sentinel-like figure of the cell vial is suggestive of a period post-anatomy.) Nina Sellars © 2018.

Figure 12. Bernhard Siegfried Albinus [anatomist] and Jan Wandelaar [artist], Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani, 1741. Tabulae I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VIII. Copperplate engravings with etching. Wellcome Collection. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution International (CC BY 4.0).

Figure 13. Juan Valverde de Amusco [anatomist], Anatomia del corpo humano … Rome, 1559. Copperplate engraving. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Public domain.

Figure 14. Henry Gray [anatomist] and Henry Vandyke Carter [artist], Thoracic Spine Anatomy. In Gray's Anatomy Textbook (1858), 219. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Public domain.

BACKGROUND IMAGE. Stelarc and Nina Sellars, Blender (installation of artwork at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia), 2016. Photograph courtesy of Jaden A. Hastings © 2016. Blender was created in collaboration with the performance artist Stelarc. Both artists underwent surgery to remove biomaterials (from Stelarc’s torso and Sellars’ limbs). The extracted biomaterials, from the bodies of both artists, are housed in a custom-built blender of anthropomorphic dimensions. Every few minutes Blender automatically circulates its contents via a pneumatic actuator connected to a system of compressed air pumps. The click of the solenoid switch operating the blending mechanism has been subtly amplified: with added distortion and digital delay it provides an audible pulse to a liquid body. Engineering by Adam Fiannaca and sound design by Rainer Linz. Blender was created in 2005 for the Teknikunst Festival 05 Contemporary Technology Festival, Melbourne, Australia, and exhibited at the Meat Market Gallery, Melbourne (co-curated by Kristen Condon and Amelia Douglas). Blender was rebuilt in 2016 for the exhibition, New Romance: Art and the Posthuman, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, curated by Anna Davis.

BACKGROUND IMAGE. Stelarc and Nina Sellars, Blender (detail of artwork—human fat in suspension, Meat Market Gallery, Melbourne, Teknikunst Festival 05), 2005. Photograph courtesy of Stelarc © 2005.

BACKGROUND IMAGE. Stelarc and Nina Sellars, Blender (Nina Sellars with Blender, Meat Market Gallery, Melbourne, Teknikunst Festival 05), 2005. Photograph courtesy of Stelarc © 2005.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albinus, Bernard Siegfried. Tabulae Sceleti Et Musculorum Corporis Humani. 1749. Londini: Typis H. Woodfall. Impensis Johannis Et Pauli Knapton, M.DCC.XLIX.

Art Bites: Biogenesis, series 1, episode 2, ‘Sentinels’, directed by Steven Alyian, aired 10 August 2019, ABC iview, accessed 31 May 2020, iview.abc.net.au/show/art-bites-biogenesis.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010. doi.org/10.1017/s1537592710003464.

Fat Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Body Weight and Society (2012–continuing). Edited by Esther Rothblum.

Fredman, Rafi, Adam J. Katz and Charles Scott Hultman. ‘Fat Grafting for Burn, Traumatic, and Surgical Scars’. Clinics in Plastic Surgery 44, no. 4 (July 2017): 781–91. doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2017.05.009

Jianu, Dana, Oltjon Cobani and Stefan Jianu. ‘Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine and Plastic Surgery: Perspective from Personal Practice’. In Pancreas, Kidney and Skin Regeneration: Stem Cells in Clinical Applications, edited by Phuc Van Pham, 273–88 Cham: Springer, 2017. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55687-1_12

Kember, Sarah and Joanna Zylinska. Life After New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8796.001.0001

Kuriyama, Shigehisa. The Expressiveness of the Body: And the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. New York: Zone Books, 1999.

Mouritsen, Ole G. Life as a Matter of Fat: The Emerging Science of Lipidomics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2005.

Pond, Caroline, M. The Fats of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Rosen, Evan D. and Bruce M. Spiegelman. ‘What We Talk about When We Talk about Fat’. Cell 156, no.1–2 (2014): 20–44. doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012

Sellars, Nina. ‘The Life and Death of Anatomy’. In Bridging Open Boundaries, as Part of the V&A Digital Design Weekend 2017, edited by Irini Papadimitriou, Andrew Prescott and Jon Rogers, 40–43. London: Uniform Communications, 2017. Archived online, DigiTranGlasgow, AHRC Digital Transformations, University of Glasgow.

Sellars, Nina. ‘Sentinels’. In Unhallowed Arts, edited by Laetitia Wilson, Oron Catts and Eugenio Viola, 100–03. Perth: UWA Publishing, 2018.

Snell, Bruno. The Discovery of the Mind: The Greek Origins of European Thought. Translated by T. G. Rosenmeyer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953.

Standring, Susan, ed. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier Limited, 2015.

World Health Organization. ‘Tenfold Increase in Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in Four Decades: New Study by Imperial College London and WHO’. WHO News Release, accessed 31 August 2019.

Zuckerman, Solly Baron. New System of Anatomy: A Dissector’s Guide and Atlas. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

This essay should be referenced as: Nina Sellars, ‘Fat Matters: Fluid Interventions in Anatomy’. In Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body, edited by Natalie Köhle and Shigehisa Kuriyama. Asian Studies Monograph Series 14. Canberra, ANU Press, 2020. doi.org/10.22459/FM.2020

MORE FLUID TALES

Introduction

1. Manipulating Flow

2. Incorporating Flow

3. Structuring Flow

Fat Matters

Nina Sellars