SPIRIT, SWEAT AND QI

.

I had come to Tzu-Chih hospital to learn about phlegm in the contemporary practice of traditional Chinese medicine. But Dr Chen chose to show me cases of acute stroke. The connection between stroke and phlegm that he had in mind wasn’t the gurgling cough that I had learned to associate with a phlegm-filled chest. Nor was he thinking of the mucus that was accumulating in the ubiquitous suction traps mounted at his patients’ bedside, or of the tiny phlegm globules that he taught me to palpate in the subcutaneous tissues of those who have suffered a stroke. What Dr Chen meant to show me was:

‘phlegm blocking the heart orifices’

tan mi xinqiao 痰迷心竅.

Unlike biomedicine, which traces strokes to cerebral infarction, contemporary Chinese medicine blames heart orifices blocked by phlegm for the loss of perception and mobility. My visit to the ICU left me with a strong sense of how dangerous phlegm could be.

But it also made me wonder: What is phlegm, really? What are heart orifices? How does phlegm block these orifices? And how did all these notions develop?{{1}}{{{The character qiao 竅 means ‘orifice’ or ‘aperture’. In the more common meaning, xinqiao refers to the tongue as one of the ‘seven sensory orifices’ (qiqiao 七竅). In the less common meaning, xinqiao refers to mysterious orifices of the heart itself. The discourse of the seven sensory orifices goes back to one of the Inner Chapters of the Zhuangzi 莊子 (350–250 BC). See Irmgard Enzinger, Ausdruck und Eindruck: Zum Chinesischen Verständnis der Sinne (Lun Wen – Studien Zur Geistesgeschichte Und Literatur in China, Book 10, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 2006), 58–65. Xinqiao in the meaning of heart orifices is not attested in the Neijing. But the Nanjing already describes seven holes and three hairs of the heart (qikong sanmao 七孔三毛). (Huangdi bashiyi nanjing, 42, ‘Zangfu dushu’ 藏府度數). See Paul Unschuld, Nan-ching, the Classic of Difficult Issues (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 417.}}}

The Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor (c. 100 BC) makes no mention of either heart orifices (xinqiao 心竅) or phlegm (tan 痰). It attributed strokes, instead, to attacks of wind (zhongfeng 中風).

The word tan 痰 (phlegm) first appears in Chinese medical writings around 200 AD, as an adjective modifying drink. ‘Phlegmy drink’ (tanyin 痰飲) was a thin and fairly mobile liquid:

Water that sloshes around the intestines, making a rumbling sound, is called ‘phlegmy drink’.{{2}}{{{Chinese: 水走腸間,瀝瀝有聲,謂之痰飲. Zhang Zhongjing 張仲景 (c. 150–219 AD), Essential Synopsis of the Golden Cabinet 金匱要略 (c. 210), juan 12, ‘Tanyin kesou bing maizheng bingzhi 痰飲咳嗽病脈證并治’. The character tan 痰 in this passage was originally written as dan 淡. It was replaced with the character tan in later texts. For details, see Natalie Köhle, ‘A Confluence of Humors: Āyurvedic Conceptions of Digestion and the History of Chinese Phlegm (tan 痰)’, Journal of the American Oriental Society 136, no. 3 (2016): 466–69.}}}

Understood as a non-physiological (non-bodily) fluid, ‘phlegmy drink’ was an imbibed liquid that wasn’t fully digested or absorbed, and thus lingered in the belly, audibly sloshing.

Over the next 400 years, phlegm became an independent substance. The first etiological treatise in the history of Chinese medicine, Treatise on the Origins and Symptoms of All Diseases (610), identified phlegm as a transformation of stagnant drool (xian 涎).{{3}}{{{Chinese: 痰者,涎液結聚在於胸膈. Chao Yuanfang, Zhubing yuanhou lun, juan 3, ‘Xulao tanyin hou’ 虛勞痰飲候. Xian (‘drool’) was saliva out of place. It was one of the specific bodily fluids derived from ye 液, the fluid associated with the spleen. See Huangdi neijing suwen, 23, ‘Xuanming wuqi’ 宣明五氣. For a discussion of xian, see Köhle, ‘Phlegm (tan 痰): Toward a History of Humors in Early Chinese Medicine’ (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2015), 185–95.}}}

Phlegm came to be understood as a product of stasis, something that appeared when flow faltered. Instead of a watery liquid just sloshing in the intestines, it was now often imagined as a viscous substance, like paint or glue (ru jiao qi 如膠漆), which could also stagnate in the hypochondrium, just above the diaphragm.{{4}}{{{Tao Hongjing, Mingyi bielu jijiao ben, 227. Ctext.}}}

The Song dynasty (960–1261) witnessed even greater changes. Whereas phlegm had previously been associated merely with weak digestion and circulation, the explanation of its causes now came to stress external pathogens and the inner turmoil of emotions, both of which generated fire (huo 火) or heat (re 熱). According to this new understanding, this fire would condense and become ‘heat congestion’ (fuyu 怫鬱) when trapped inside the body.{{5}}{{{The new classification system is described most systematically in Chen Yan’s 陳言 Sanyin jiyi bingzheng fanglun 三因極一病証方論 (1174), juan 13, ‘tanyin xulun 痰飲敘論’, but many other important authors of the Jin (115–1234) and Song periods, such as Yan Yonghe 嚴用和 (1206–68) and Liu Wansu 劉完素 (fl. c. 1110–1200), made implicit use of it.}}}

It was this heat congestion that transformed bodily fluids into phlegm.{{6}}{{{Body fluids here include both the generic type of jinye 津液 fluids, as well as their five transformations: ‘drool’ (xian), saliva (tuo 唾), sweat (han 汗), tears (lei 淚) and nasal mucus (ti 涕). See Huangdi neijing suwen, 23, ‘Xuanming wuqi’ 宣明五氣 and the discussion in Köhle, ‘Phlegm (tan 痰)’, 185–95.}}} The idea of phlegm, in other words, was now closely bound to the imagination of trapped heat.

It was a dramatic change. What was once a cold humour that was treated with warming drugs, had transmuted into a product of fire. And the key to this transmutation was the notion of fire that couldn’t escape the body.

Conceptions of sickness in classical Chinese medicine stressed two main sources of vulnerability: the leaking out of vital essences from within and the intrusion of pathogens from without. Pores, consequently, played a decisive role in health. Firm pores prevented vital loss and pathological influx. Open pores opened the body to leakage and invasion.{{7}}{{{See Shigehisa Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (New York: Zone Books, 1999), 222–23, 258–59. The Chinese terms for pores are xuanfu 玄府 and couli 腠理. Both are attested in the Neijing, where—generally speaking—xuanfu refer to sweat pores, while couli refer to interstitial structures in-between skin, and subcutaneous and muscular tissues.}}}

In the Song dynasty, however, this classical anxiety about open pores came to be complemented by a new and opposing concern. This new anxiety centred on external pathogens or inner passions generating dense heat and causing pores to close. Trapped inside, and prevented from escaping from the body as sweat, this heat would become even more intense, which in turn would cause the pores to seal themselves even more tightly. Phlegm was produced when the dense heat generated by this vicious cycle met the steam of trapped sweat.

Here was a new conception of human vulnerability—a shift of concerns from an ‘open body’, prone to dissipation and invasion …

… to a ‘closed body’ easily congested by clogged pores and filled with phlegm.

Therapeutic interventions thus started to emphasise opening closed pores. Discussions of how to ensure the free passage of sweat and qi through the pores proliferated.

The theory of subtle pores (xuanfu 玄府) advanced by the Northern Song scholar Liu Wansu 劉完素 (fl. c. 1100–1200) exemplified this new discourse:

The skin’s sweat pores are orifices that drain qi and bodily fluids … [but in like manner], all material objects have subtle pores. Bodily organs, skin, hair, muscles, flesh, tendons, membranes, bones, marrow, claws and teeth—all the myriad things in this world—have subtle pores. Subtle pores are the doors and pathways for the entry, exit, rise, and fall of qi.{{8}}{{{Chinese: 然皮膚之汗孔者,謂洩氣液之孔竅也 … 然玄府者,無物不有,人之臟腑、皮毛、肌肉、筋膜、骨髓、爪牙,至於世之萬物,盡皆有之,乃氣出入升降之道路門戶也. Liu Wansu, Methods for Tracing Illnesses, 230 (SKQS and Ctext wiki).}}}

Liu saw subtle pores as the essential conduits for the movement of fluids and qi inside, into and out of the body.{{9}}{{{Although xuanfu was an old term, already attested in the Neijing, Liu Wansu expanded its meaning well beyond this original sense of openings for the release of sweat, and applied it to a wide range of porous structures in the body. For this reason, I translate xuanfu 玄府 as ‘subtle pores’.}}}

Nor was their importance limited to the body. All things in the world, according to Liu, were organised around subtle pores. They were the essential orifices that enabled fluid flow. Without them, qi couldn’t circulate through matter. But these pores were easily blocked, and their blockage regularly caused congestion and stagnation.

This last point is crucial. Although the theory of subtle of pores ostensibly made the body more porous, its rise mirrored a growing sense of diminished fluidity and material resistance to flow. It was precisely heightened concerns about stagnation and the tenuous fragility of flow that prompted the search for ever subtler channels, and the emphasis on measures to open closed or blocked pores.

In classical medicine, pores had figured predominantly as inroads for disease: now, they were conceived more as vents for releasing sweat and heat. Classical medicine had worried about the loss of vital essences through open pores: now, the overriding fear was about heat trapped inside by closed pores—heat manifest in phlegm.

PERCEPTION

is spirit traversing pores

For Liu Wansu, the unfettered flow of qi through the body’s myriad pores was also a precondition for perception:

The function of eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, mind, and perception proceeds in all cases from the uninhibited entry, exit, rise, and fall of qi. If blocked, [these orifices] are unable to operate. When eyes do not see, ears do not hear, the nose does not smell, the tongue does not taste, tendons wither, bones stiffen, teeth decay, hair thins, skin numbs, and bowels do not open, it is because hot qi, and heat congestion cause closed and occluded subtle pores, which is the reason for qi, blood, nutritive and protective qi, and spirit being unable to rise and fall, and exit and enter [the body].{{10}}{{{Chinese: 人之眼、耳、鼻、舌、身、意、神識,能為用者,皆由升降出入之通利也,有所閉塞者,不能為用也。若目無所見,耳無所聞,鼻不聞臭,舌不知味,筋痿骨痹,齒 腐,毛髮墮落,皮膚不仁,腸不能滲泄者,悉由熱氣怫鬱,玄府閉密而致,氣液、血脈、榮衛、精神、不能升降出入故也. Liu Wansu, Methods for Tracing Illnesses, 230. (SKQS and Ctext wiki).}}}

Liu Wansu, Methods for Tracing Illnesses to Their Origins, 230

Fluids flow, qi moves, spirit travels—but only if the pores are unencumbered. The free communication of subtle pores was now the very foundation of life, supporting everything from the tendons and bones that gave the body visible structure to the subtler streams of spirit that allowed people to see and hear, talk and move.

Liu’s claims were as old as they were innovative and surprising. The easy flow of fluids and qi had been central to the art of nurturing life (yangsheng 養生) since ancient times. Physicians had long imagined ‘spirit’ (shen 神) as an exquisitely refined qi residing in the heart and going out from there to apprehend the world. Thus they had touted unblocking the ‘seven sensory orifices’ (qiqiao 七竅)—eyes, ears, nose, mouth, tongue—as the secret to sharpening perception.{{11}}{{{Catherine Despeux, ‘La notion de shen dans la médicine chinoise antique’, Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident 29 (2007): 71–94.}}} But, until Liu, no-one had claimed that qi—and even spirit—needed pores to circulate through the body.

In this respect, Liu's theory of subtle pores epitomised a major shift, a reconceptualisation of matter. Matter was now thought so dense that even spirit—the finest, most ethereal form of qi—needed channels in order to course through it.

The connection between phlegm-blocked heart orifices and stroke would be developed in Ming times (1368–1644).{{12}}{{{The phrase ‘phlegm blocking the heart orifices’ (tan mi xinqiao 痰迷心竅) appears in many Ming medical treatises—for example, Zhu Chongzheng’s 朱崇正 (fl. Ming Jiaqing period 明嘉靖 1521–67) Renzhai Zhenzhi fanglun fuyi fang 仁齋直指附遺方, an addendum to Yang Shiying’s 楊士瀛 (fl. thirteenth century) Renzhai Zhenzhi fanglun 仁齋直指方論 (1264). In this treatise tan mi xinqiao 痰迷心竅 is already associated with stroke (zhongfeng 中風) (juan 26, ‘Fu qu tu fang 附取吐方’, SKQS). In another part of the same addendum, the similar phrase ‘phlegm blocking heart and diaphragm’ (tan mi xin ge 痰迷心膈) is used (juan 11, ‘xuanyun 眩運’, SKQS). Several references to heart orifices that ‘congeal’ (ningzhi 凝滯) or are ‘blocked’ (mi 迷) by phlegm or blood, or both, and need to be ‘made passable’ (tong 通) from such obstructions, also occur. Most of these cases are describing palpitations and loss of speech after fright.}}}

But the critical development was Liu Wansu’s earlier theory of subtle pores. Like subtle pores, heart orifices were imagined as minute, structural pathways through which qi and spirit had to pass in order for a person to perceive and engage with objects in the outside world. When these pathways were blocked, qi and spirit would be trapped inside the body, and the person would be unable to perceive, respond or move—that is, suffer the symptoms of stroke.

Heart orifices, then, were direct descendants of subtle pores. Both notions were rooted in the shift in intuitions about matter and flow that occurred in Song China, when congested heat and obstructing phlegm rose to the forefront of medical concerns; when anxieties shifted from open to closed pores; when matter became more impervious and flow more fragile, and life more easily stifled. When spirits required release.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Dr Chen Chien-lin, head of the Chinese medicine unit at Tzu-Chih hospital who welcomed me to his clinic in May 2017. I also gratefully acknowledge the financial support I received from the Asia-Pacific Innovation Program, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, for field research in Taiwan. Preliminary versions of this essay were presented at the International Congress of History of Science and Technology, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, 2017; the International Congress on Traditional Asian Medicines IX, University of Kiel, 2017; and the Deutscher Verein für Chinastudien Conference, Berlin Institute of Technology, 2018.

GLOSSARY

body fire, body heat huo 火, re 熱

body fluids [generic] jinye 津液, ye 液

art of nurturing life yangsheng 養生

drink fluid yin 飲

drool xian 涎

heart orifice(s) xinqiao 心竅

heat congestion yu 鬱, fuyu 怫鬱

glue jiao 膠

paint qi 漆

phlegm tan 痰

phlegm blocking the heart orifices tan mi xinqiao 痰迷心竅

phlegmy drink tanyin 痰飲

pores couli 腠理, xuanfu 玄府

qi 氣

seven sensory orifices qiqiao 七竅

spirit shen 神, jingshen 精神

stroke, wind stroke zhongfeng 中風

subtle pore(s) xuanfu 玄府

sweat pore(s) hankong 汗孔

IMAGE AND FILM CREDITS

Listed in the order in which they first appear in the essay.

Entrance door to an Intensive Care Unit at Tzu-Chih hospital, Taipei. Huang Ching-pin, 2018. Huang Ching-pin © 2018. Reproduced with permission of the photographer. Modified by author.

Heart. Figure 13 in Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Physiology for Young People Adapted to Intermediate Classes and Common Schools, National Department of Scientific Instruction (1884), 95. Made available by the Internet Archive. Public domain. Taken from Wikimedia. Modified by author.

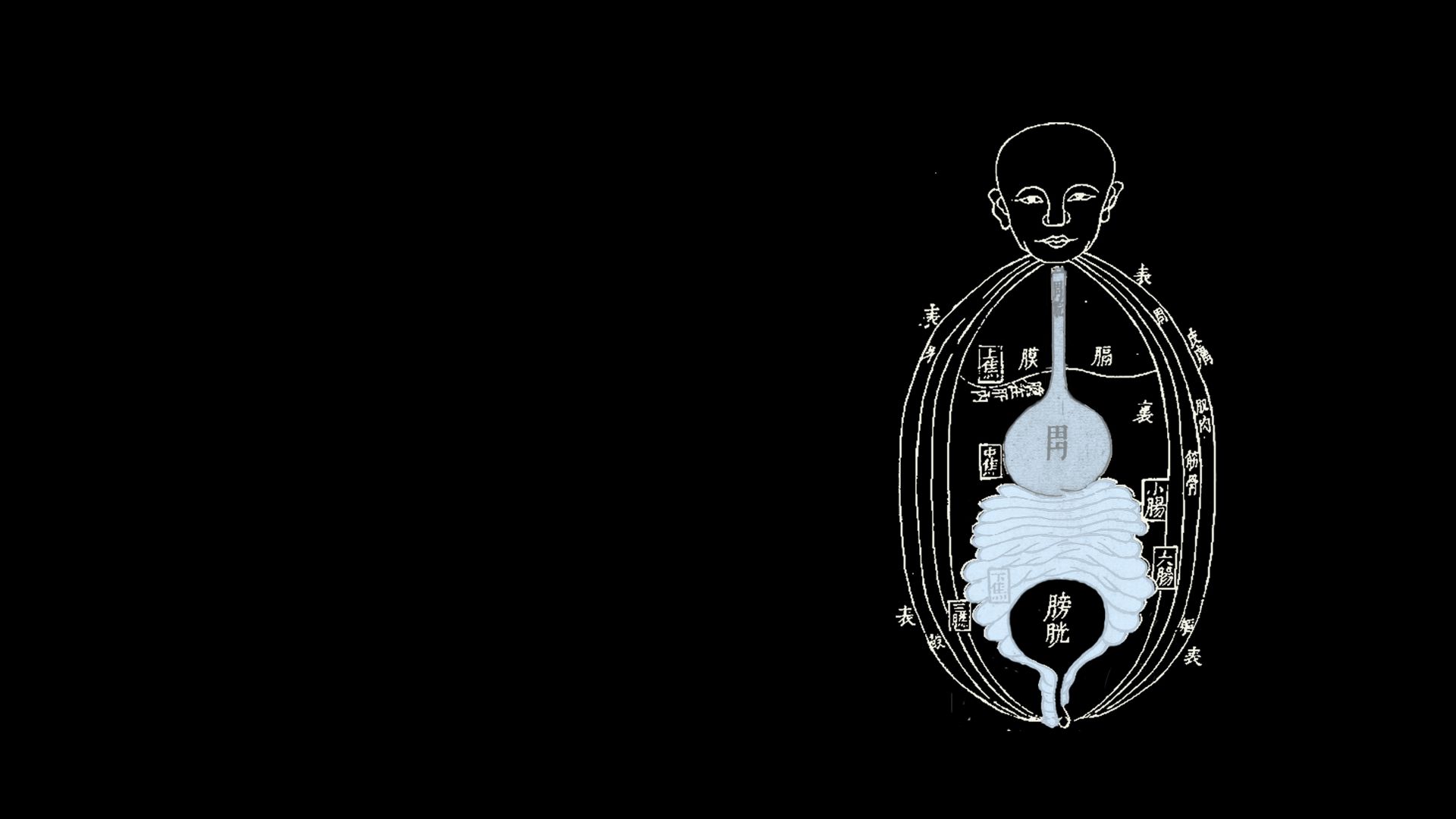

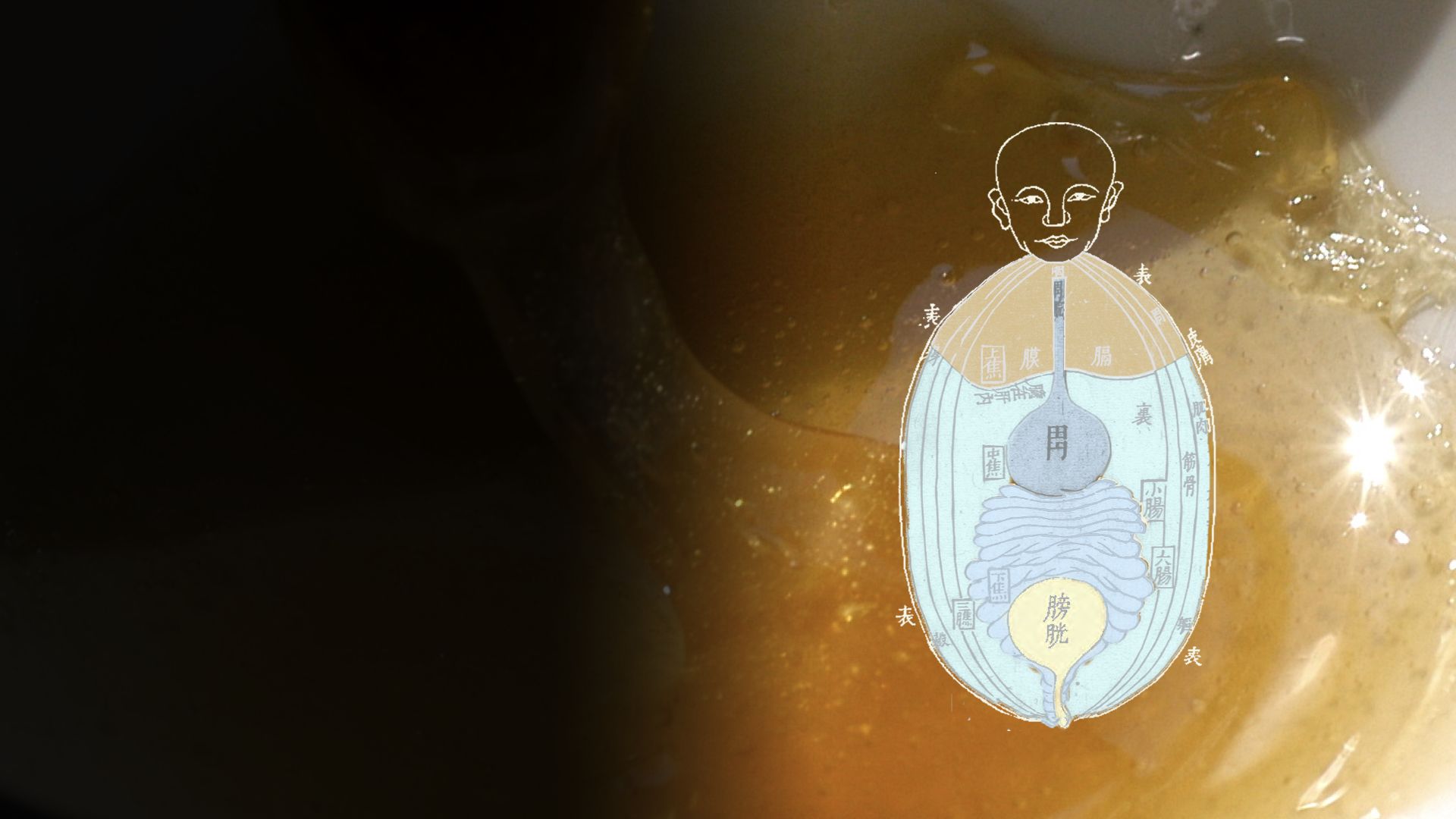

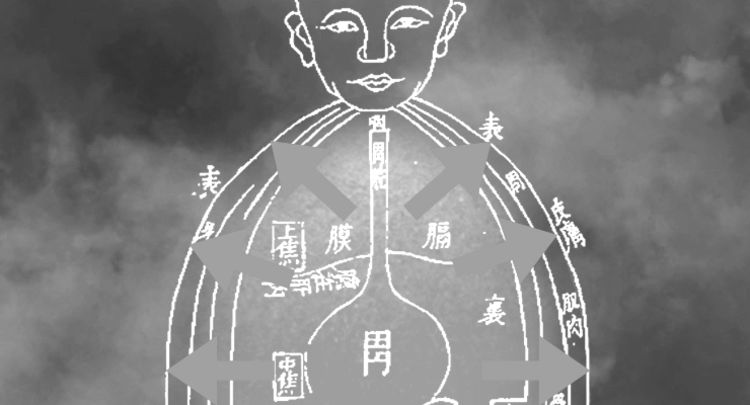

Torso. Transmission of Yang diseases from exterior to interior. In Lu Yuncheng, Renshen biaoli yinyang tu, 1738. Wellcome Collection L0038020. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution International (CC BY 4.0). Modified by author.

Water. Taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under a Pixabay License.

Glue. Simon Eugster, 2008. Simon Eugster © 2008. Detail. Taken from Wikipedia. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Abstract tissue. Lena Springer and Natalie Köhle, 2018. Lena Springer and Natalie Köhle © 2018.

Storm clouds. Savvas Karampalasis, Abstract Storm Clouds Gathering Seamless Loop, 2016. 3D COR—Savvas Karampalasis © 2016. Taken from YouTube. Reproduced by license. Modified by author.

Fire flow. CyberWebFX, Inkdrop in Water, n.d. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Unported (CC BY 3.0). Modified by author.

Tissue. J. Jana, Dense Connective Tissue, 2015. J. Jana © 2015. Taken from Wikipedia. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Bone structure. Patrick Siemer, Bone Structure, 2008. Patrick Siemer © 2008. Taken from Wikimedia. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution Generic (CC BY 2.0).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Chao Yuanfang 巢元方 (581–618). Zhubing yuanhou lun 諸病源候論 [Treatise on the Origins and Symptoms of All Diseases] (610). Siku quanshu 四庫全書. Wenyuan ge Si ku quan shu dian zi ban 文淵閣四庫全書電子版. Hong Kong: Chinese University Hong Kong Press, 2002 (henceforth: SQKS); Chinese Text Project Wiki (henceforth: Ctext wiki).

Chen Yan 陳言 (fl. twelfth century). Sanyin jiyi bingzheng fanglun 三因極一病証方論 (1174). SKQS; Ctext wiki.

Huangdi bashiyi nanjing 黃帝八十一難經 [Classic of the Yellow Emperor’s Eighty-One Difficult Issues] (c. 200 AD). Chinese Text Project (henceforth: Ctext).

Huangdi neijing 皇帝內經 [Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor] (c. 100 BC). Ctext.

Liu Wansu 劉完素 (fl. c. 1110–1200). Suwen xuanji yuanbing shi 素問玄機原病式 [Methods for Tracing Illnesses to Their Origins]. SQKS; Ctext wiki.

Tao Hongjing (456–536). Mingyi bielu jijiao ben 名醫別錄:輯較本. Edited by Shang Zhijun 尚志钧. Beijing: Renmin weisheng chubanshe, 1986; Ctext wiki.

Yang Shiying 楊士瀛 (fl. thirteen century). Renzhai Zhenzhi fanglun 仁齋直指方論 (1264), with an addendum by Zhu Chongzheng 朱崇正 (fl. Ming Jiaqing period 明嘉靖 1521–1567), based on his lost Renzhai Zhenzhi fanglun fuyifang 仁齋直指附遺方 (1550). SKQS; zh.wikisource.

Zhang Zhongjing 張仲景 (c. 150–219 AD). Jingui yaolüe 金匱要略 [Essential Synopsis of the Golden Cabinet] (c. 210). Ctext.

Zhu Chongzheng 朱崇正 (fl. Ming Jiaqing period 明嘉靖1521–67). Renzhai Zhenzhi fuyifang 仁齋直指附遺方 (1550). See Yang Shiying 楊士瀛.

Zhuangzi 莊子 (350–250 BC). Ctext.

Secondary Sources

Despeux, Catherine. ‘La notion de shen dans la medicine chinoise antique’. Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident 29 (2007): 71–94. doi.org/10.3406/oroc.2007.1086

Enzinger, Irmgard. Ausdruck und Eindruck: Zum Chinesischen Verständnis Der Sinne. Lun Wen – Studien Zur Geistesgeschichte Und Literatur in China, Book 10. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 2006.

Köhle, Natalie. ‘A Confluence of Humors: Āyurvedic Conceptions of Digestion and the History of Chinese “Phlegm” (tan 痰)’. Journal of the American Oriental Society 136, no. 3 (2016): 465–93. doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0465

Köhle, Natalie. ‘Phlegm (tan 痰): Toward a History of Humors in Early Chinese Medicine’. PhD diss., Harvard University, 2015.

Kuriyama, Shigehisa. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. New York: Zone Books, 1999.

Unschuld, Paul. Nan-ching, the Classic of Difficult Issues: With Commentaries by Chinese and Japanese Authors from the Third through the Twentieth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

This essay should be referenced as: Natalie Köhle, ‘Spirit, Sweat and Qi’. In Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body, edited by Natalie Köhle and Shigehisa Kuriyama. Asian Studies Monograph Series 14. Canberra, ANU Press, 2020. doi.org/10.22459/FM.2020

MORE FLUID STORIES

Introduction

1. Manipulating Flow

2. Incorporating Flow

3. Structuring Flow

Spirit, Sweat and Qi

Natalie Köhle