Fluid Feelings

A Strange Cure

It was a strange cure.

But then again, the condition it treated was strange, and it’s unclear whether our own doctors even today would know what to do. After all, it is rare to meet a man who suddenly sees everything upside down.

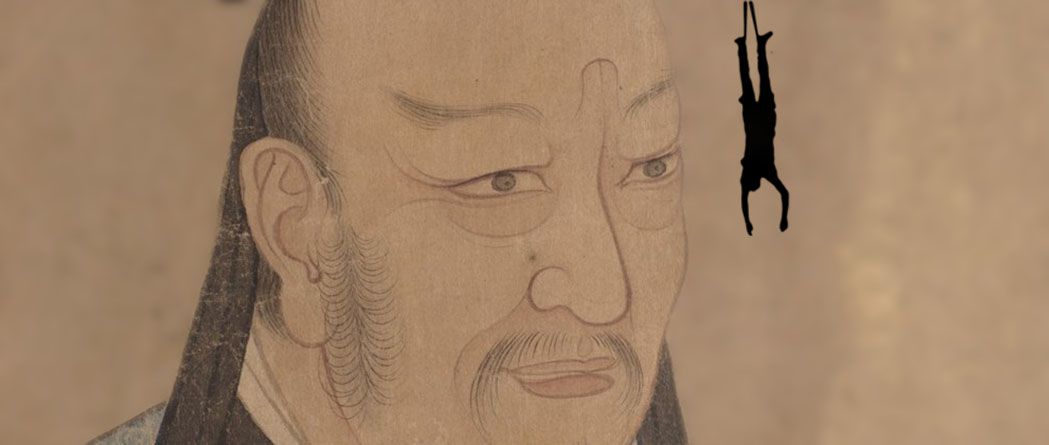

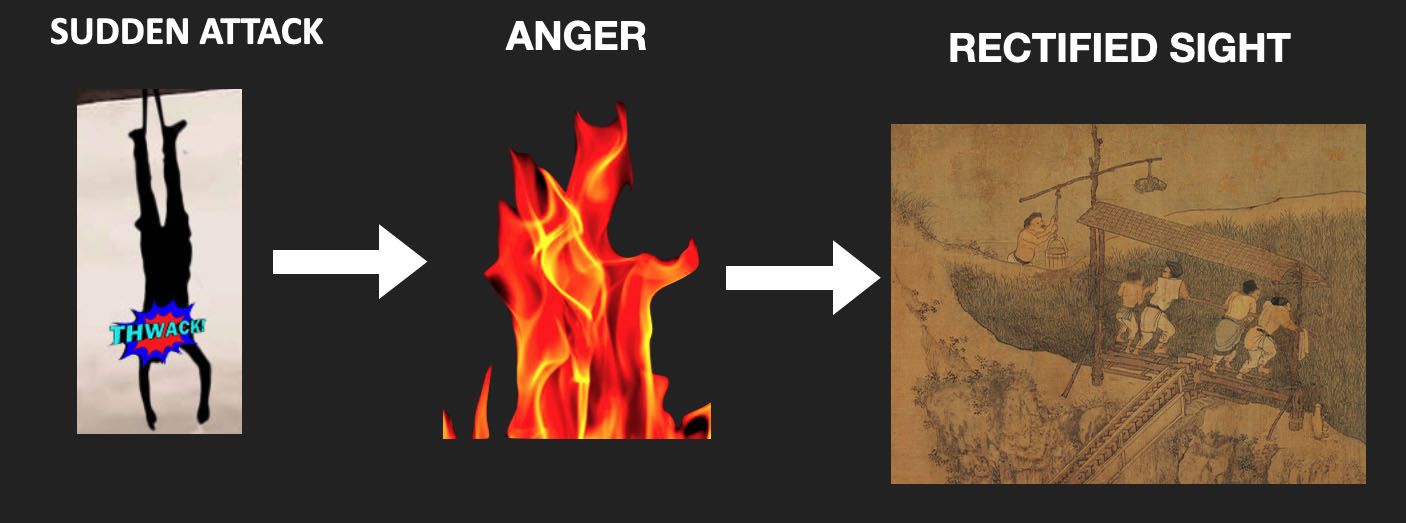

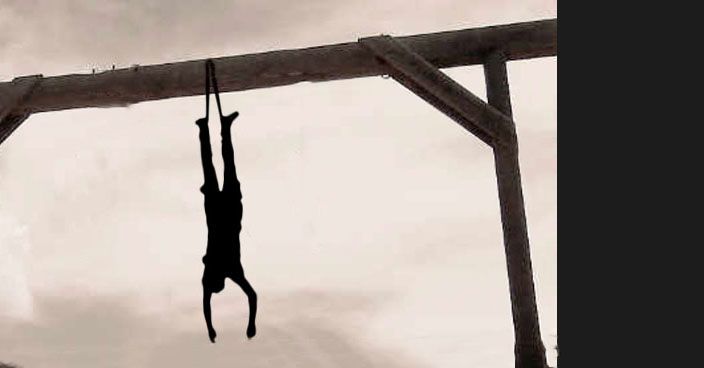

Still, the remedy proposed in seventeenth-century China may seem oddly primitive, barbaric even—the sort of treatment that only an ignorant quack might try. The way to fix this man’s inverted vision, Chen Shiduo 陳士鐸 (1627–1707) urged, was to hang him from his feet, and then, without warning, give a light rap to the head.{{1}}{{{The original text says: '天师曰:倒治者,乃不可顺,因而倒转治之也。如人病伤筋力,将肝叶倒转,视各物倒置,人又无病,用诸药罔效。必须将人倒悬之,一人手执木棍,劈头打去,不必十分用力,轻轻打之,然不可先与之言,必须动其怒气 ,使肝叶开张,而后击之,彼必婉转相避者数次,则肝叶依然相顺矣 .' In Chen Shiduo 陳士鐸, Shishi milu 石室 秘錄. [Preface 1689]. This work can be found in annotated facsimile edition from Xuanyongtang 萱永堂 print of (1730), edited by Liu Zhanghua 柳長華 et al., Chen Shiduo yixue quan shu 陳士鐸醫學全書. (Beijing: Zhongguo zhongyiyao chubanshe, 1999), 265–433. This passage appears in juan 3 (= p. 329). Ctext.}}}

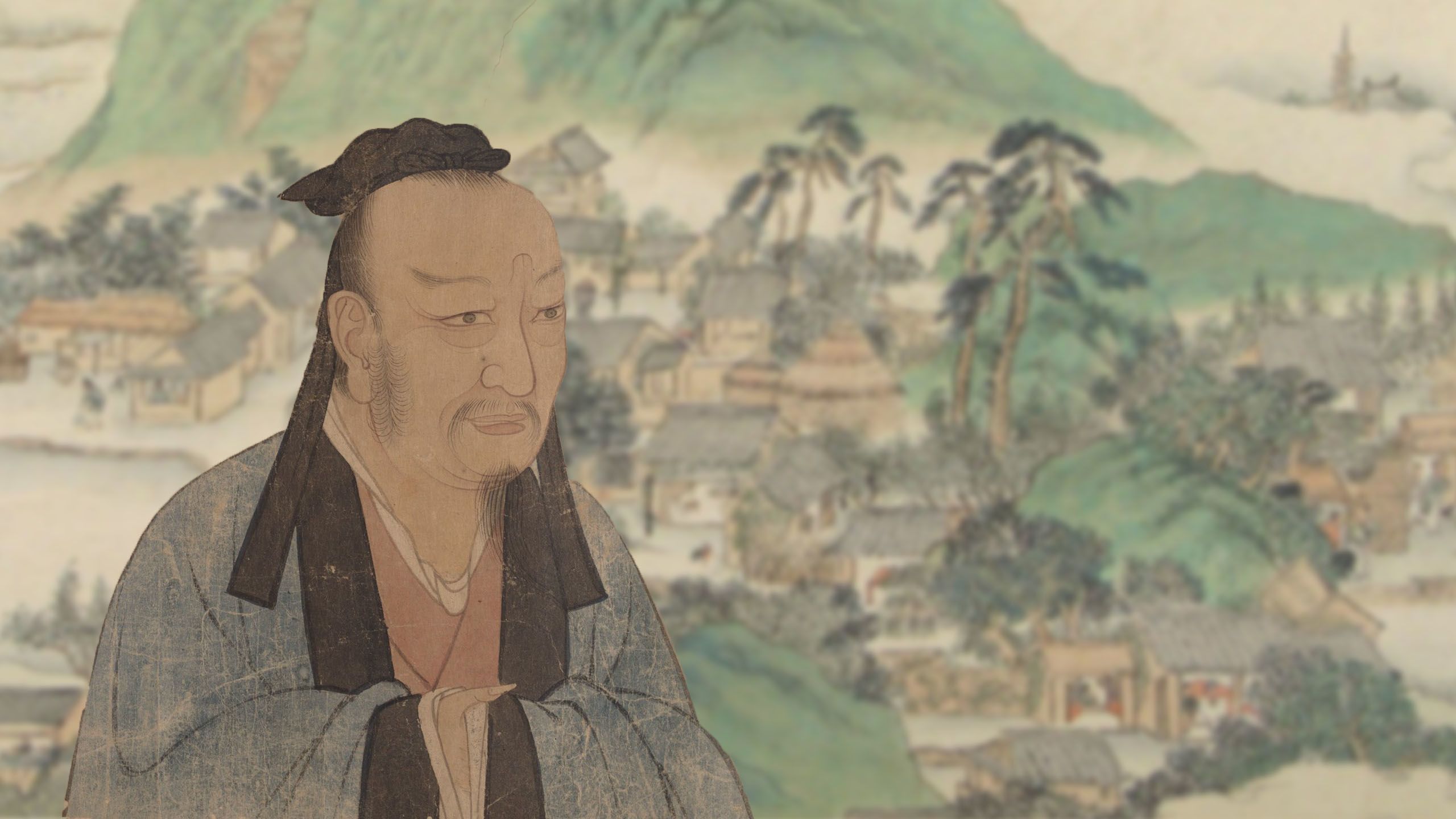

And yet, Chen Shiduo was no simple folk-healer. He was a respected physician from the rich region of Zhejiang who, in the course of his life, authored over 60 medical works, eight of which survive to this day. The rap that he proposed was firmly grounded in classical medical theory, and entirely different from the sort of frustrated whack that we might give to a broken toaster, say, in the vain hope that a dislodged gear might somehow fall back into place. Its intended target was not so much the head, but rather the flow of feelings, and the intended effect was more psychological than mechanical. Chen Shiduo’s aim was to provoke spontaneous rage. The key to rectifying the patient’s vision, he reasoned, was to make him angry.

Why did he believe this? What connection did he suppose between the pathology and the cure, between inverted sight and anger? The answer reveals much, both about his understanding of human beings and the history of emotions in China.

Emotions had long loomed large in Chinese thought, especially as a threat. Since antiquity, thinkers had fretted over their disruptive sway and devised various strategies to tame them. Controlling emotional impulses was a central concern, most notably of the influential stream of Confucianism known as lixue or the 'School of Principle', represented by the three towering authorities of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Cheng Hao, Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi.

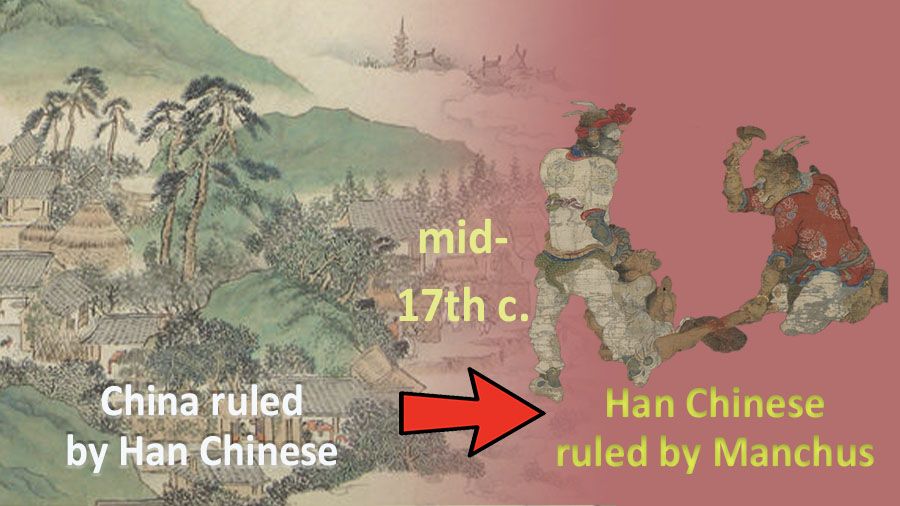

But the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a subtle shift in attitudes.

On the one hand, the decades-long transition that saw the Manchu takeover of China occasioned a widespread outpouring of passions—searing resentments and wrenching grief. Physicians regularly encountered patients suffering from lacerating, visceral pain like having ‘one's guts being torn asunder’ (chang jie yu duan 腸結欲斷), 'one's liver and lungs ripped out’ (ru ku ganfei 如刳肝肺) or ‘one's heart seared in oil’ (xin ruo fengao 心若焚膏).{{2}}{{{Wang Xiuchu 王秀楚, Yangzhou shi ri, 240–41; Angelika C. Messner, ‘Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China. Editor’s Introduction to the Thematic Section’, Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques LXVI 4 (2013): 949.}}}

On the other hand, thinkers began increasingly to explore how emotions might be harnessed as a positive force for individual self-transformation and for social change.

Chen Shiduo’s medicine mirrored his times. Not only did his writings voice fierce resentment against the foreign invaders who had taken over China, but also they reflected, more generally, the heightened contemporary attention to the inner empire of emotions. But his understanding of emotions differed markedly from ours.{{3}}{{{For a detailed discussion of the significance of the emotions in seventeenth-century medical discourses, see Angelika C. Messner, Zirkulierende Leidenschaft. Eine Geschichte der Gefühle im China des 17. Jahrhunderts [Circulating Passions: A History of Emotions in 17th-Century China]. (Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag, 2016), 187–286. Evidence for Chen’s resentment against the Manchu rulers can be found in the form of numerous medial cadences in his works on differentiating diseases, Bianzheng qiwen 辨證奇聞 and Bianzheng lu 辨証錄. See Chen Shiduo, Bianzheng qiwen, 483–89; Chen Shiduo, Bianzheng lun, 691–1010. See also Messner, Zirkulierende Leidenschaft, 63 n. 196, 65–66, n. 208.}}}

This is apparent from his treatment of the man who saw upside down.

Visceral Feelings

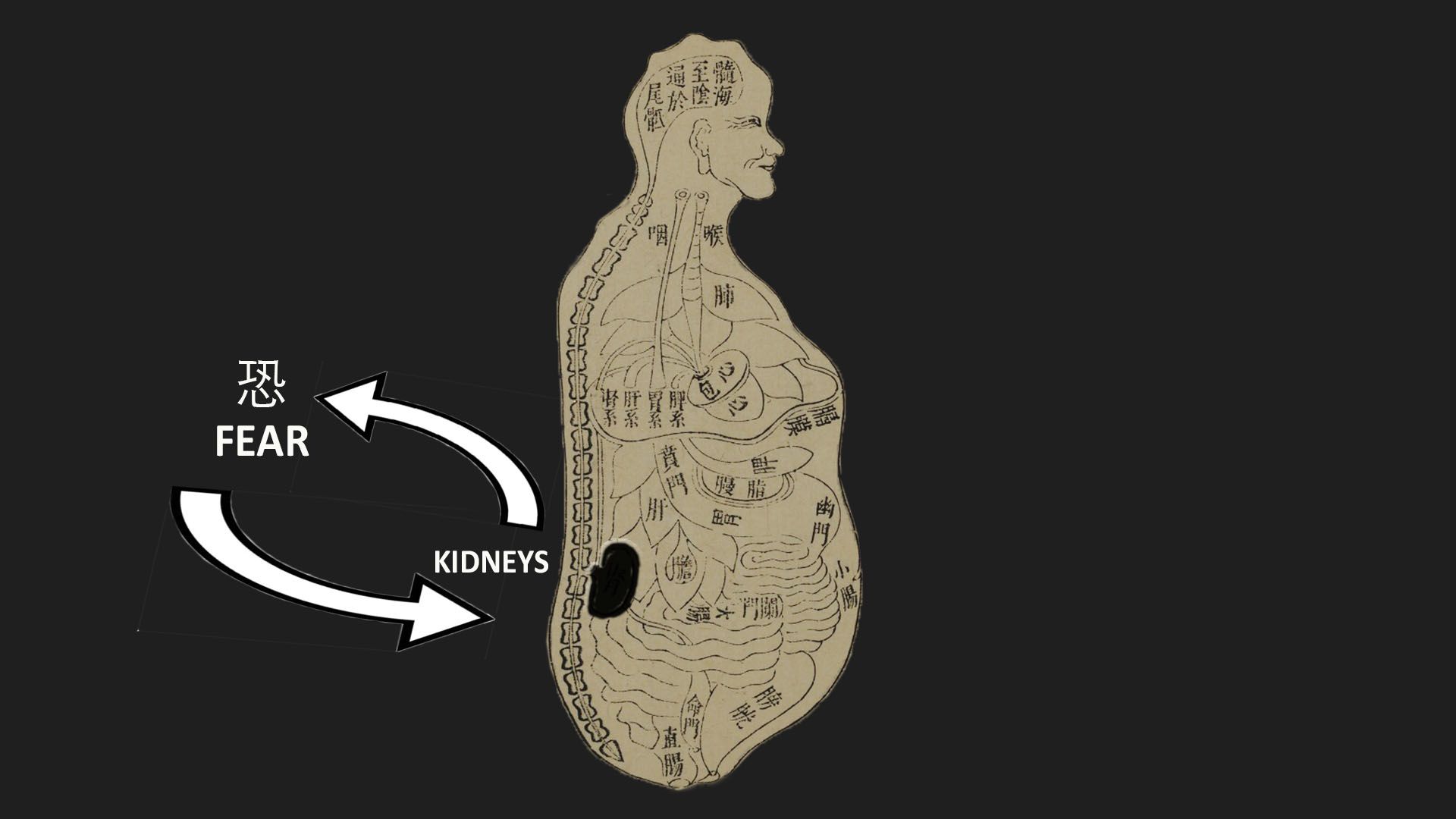

In the classical theory of Chinese medicine, humans were visceral beings. The five zang or viscera (wuzang 五臟)—the five solid organs of the lungs, heart, spleen, liver and kidneys—not only governed the life of the body, but also represented the root of all the outer capacities and expressions of a person, including the ability to see and to hear; the propensity to cry, sing or laugh; and the preference for spicy or sweet foods.

Emotions, too, were inseparable from the zang. A problem in the kidneys could cause extreme fearfulness and, conversely, frightening events could damage the kidneys.{{4}}{{{The original passage in the Suwen (juan 23 ‘宣明五氣篇第): ‘五 精 所 並: 精 氣 並 於 心 則 善, 並 於 肺 則 悲, 並 於肝 則 憂, 並 於 脾 則 畏, 並 於 腎 則 恐, 是 謂 五 並, 虛 而 相並 者 也.’ Translation: ‘When the Qi-essence [of all five viscera] accumulates in the heart, it will give rise to joy, when it collects in the lungs, it will give rise to sorrow, when it collects in the spleen, it will give rise to dread, when it collects in the kidneys, it will give rise to fear. Such are the so-called five accumulations.’ In Cheng Shide 程士徳, et al., Suwen zhushi huicui 素問注釋匯粹 (Beijing: Renmin weisheng chubanshe, 1982), 364. See also Ctext.}}}

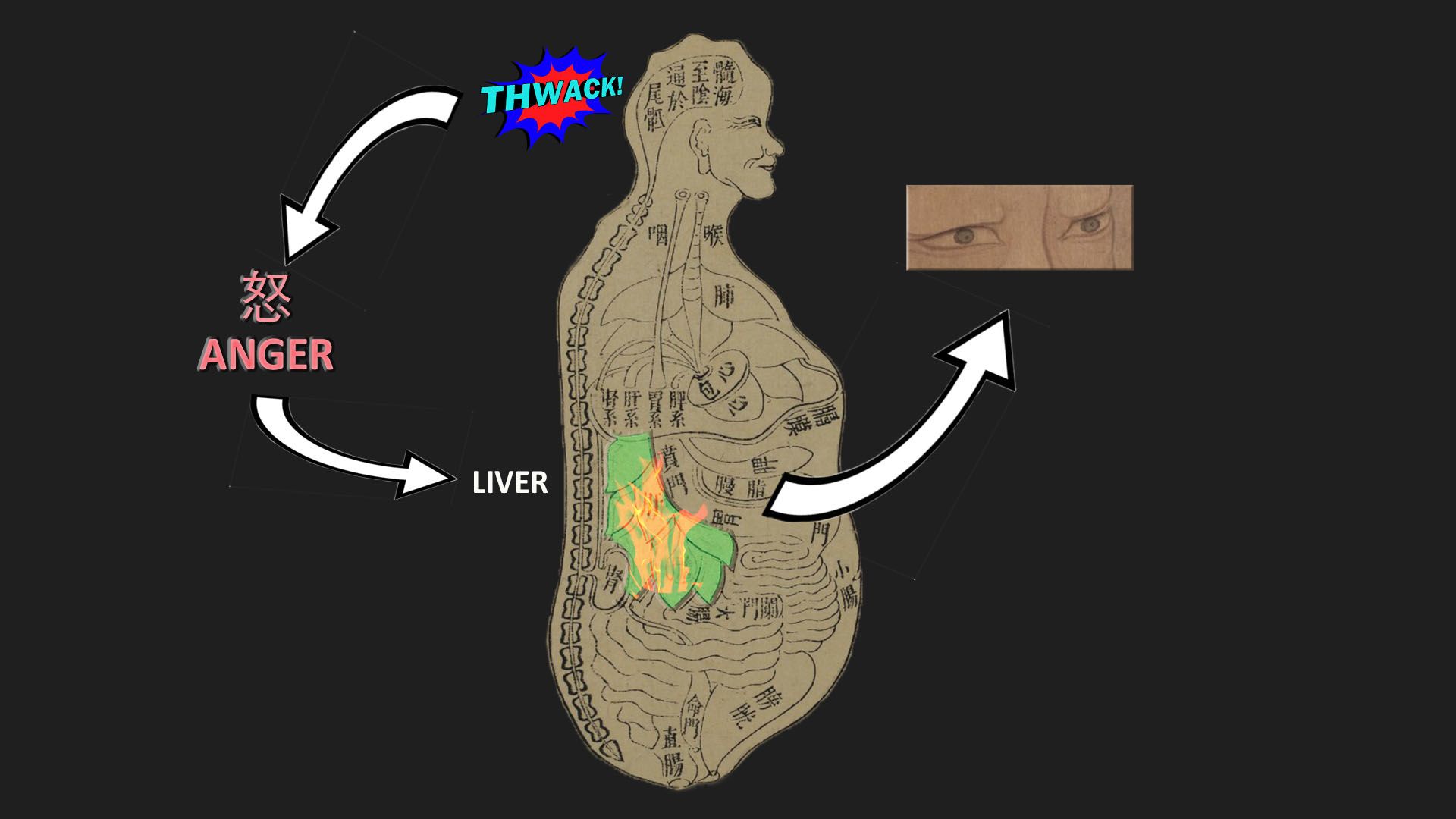

Anger was rooted in the liver. But the liver also governed the eyes. This was the logic of Chen Shiduo’s cure: aberrant vision bespoke a pathology of the liver and one of the most direct ways to alter the state of the liver was through anger, its associated emotion. Of course, the liver could be approached in many other ways, and another doctor living in another age might have chosen, more conventionally, to prescribe certain drugs and foods, or to recommend a set of exercises and changes in lifestyle. But inverted vision was an extraordinary pathology, and Chen Shiduo lived, as we’ve noted, in a period that was fixated on the potency of the passions. So he opted, instead, to treat the liver with a sudden, unexpected rap to the head—that is, by provoking a surge of anger.

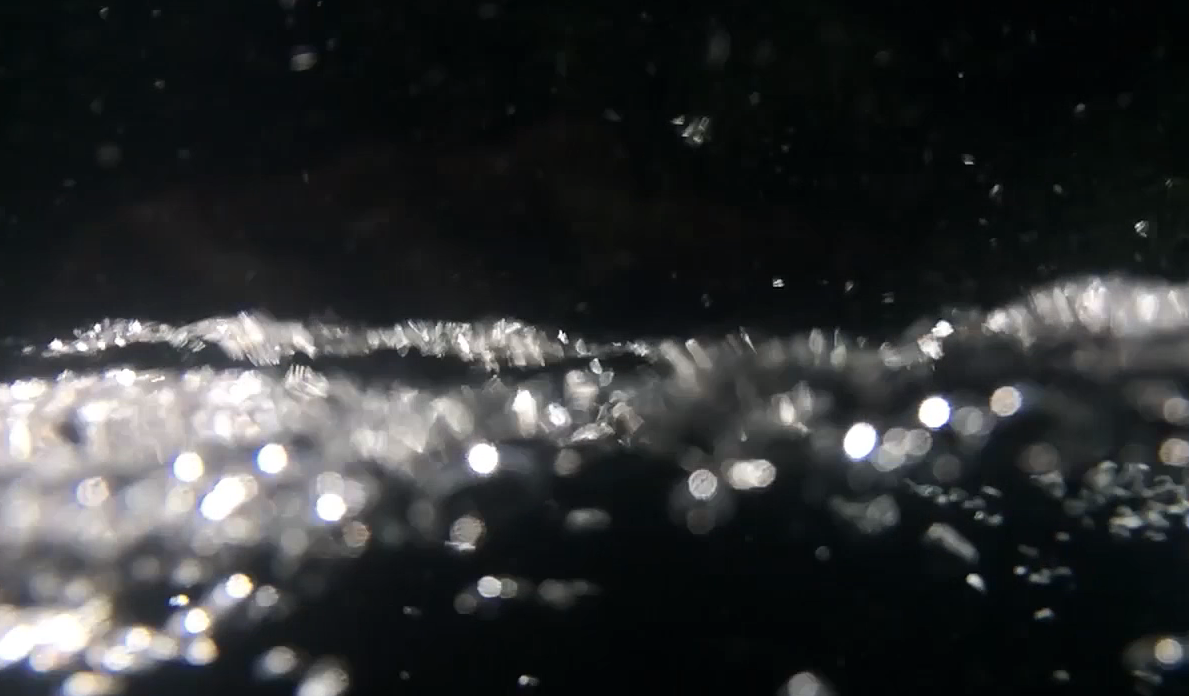

Surge is the precise word here, with its suggestion of rising and its early modern meaning of 'fountain, stream, or swell of water.' Emotion was not an abstract and private state of the soul, but rather a physical flow.

The imagination of the body in traditional China was inseparable from the imagination of fluids. Physicians sought, above all, to ensure the smooth and harmonious streaming of qi 氣. For they saw irregularities in qi’s flow—its reversals, imbalances, stagnant coagulations—at the core of most sicknesses. Emotions offered a direct reflection of such irregularities. Accumulated superabundance (taiguo 太過) in a particular organ (zang 臟), for example, could be read from pronounced expressions of its associated emotion. Extreme irascibility, for instance, bespoke an excess in the liver. At the same time, emotions also offered a powerful means of altering flow and acting upon the zang. Strong emotions could shake up the body much like violent gales shake up the earth.

By dissolving the chronic knots in the chest and restoring flow, anger could thus cure anxiety and grief (yubing 鬰病, youchou 忧愁). By unblocking phlegm stuck within the heart (tan mi xinqiao 痰迷心竅), it could resolve epileptic seizures.

It was hard to manage, to be sure. When unbridled, rage could wreak massive destruction. If repressed, it could result in crippling conditions like ‘hanging tongue’. But, carefully managed and strategically deployed, anger could be supremely effective in restoring flow.{{5}}{{{On the therapeutic use of anger, see Messner, Zirkulierende Leidenschaft, 200–23. The role of anger in the evolution of Chinese medical theory is discussed in Shigehisa Kuriyama, ‘Angry Women and the Evolution of Chinese Medicine’, in National Healths: Gender, Sexuality and Health in a Crosscultural Context, ed. Michael Worton and Nana Wilson-Tagoe (London: UCL Press, 2004), 179–89.}}}

The Angry Liver

Anger was, moreover, an intimately familiar feeling among the educated elite of Chen Shiduo’s time. In the seventeenth century, outrage against the Manchu invaders and loyalty to the previous Ming rulers led many court officials to resign their positions. Some left the bureaucracy and turned to medicine as an alternative career. Meanwhile, a growing number of scholars failed to get official posts despite having successfully passed the civil service examinations. Writings of the time abounded in expressions of frustration and grievance (naonu 惱怒), of great anger (danu 大怒), extreme anger (nu ji 怒极) and explosive anger (baonu 暴怒). But there was nothing to be done, no recourse. This was why repressed rage could congeal in the chest and turn the liver upside down, burning its lobes together into a hard, sclerotic mass. In turn, this was why there were patients, Chen Shiduo believed, like the man who saw things upside down.

Chen’s cure aimed to use a powerful surge of anger to restore motion and flow to the liver. In one sense, it was thus a kind of psychotherapy, a treatment focused on emotions. But here we must be careful. The fact that he first suspended the patient from his legs reminds us of the materiality of his conception of emotions—his commitment to a psychology based on physical flows. In contrast to yin 陰 emotions such as worry and grief, which caused qi to contract and sink down, anger was a yang 陽 emotion characterised above all by the sudden upward rush of qi—a rush that presumably would turn over the liver and loosen its lobes. A surge of anger was thus a surge of real fluids, which could flip an organ just like tumbling rapids can overturn stones.

This observation is crucial. The flow of feelings in traditional China was not simply a discursive figure of speech or a theory of subjective experience. The flow of feelings was essentially no different from—and inseparably entwined with—the flow of all the other fluids that made up the life of the body. We are tempted to say that emotions straddled the psychological and the physical—the soul and the body—but this formulation introduces distinctions alien to the qi conception of human being.{{6}}{{{See Angelika C. Messner, ‘Towards a History of the Corporeal Dimensions of Emotions: The Case of Pain’, Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques LXVI 4 (2013): 943–72; Angelika C. Messner, ‘Knowing and Doing Emotions in Times of Crisis and Radical Change’, L’Atelier du Centre de recherches historiques, Revue électronique du C.R.H. (École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales) 16 (2016): 1–18.}}}

The critical distinctions in this conception were not between a material body and an immaterial mind, but instead distinctions of flow. Essentially, anger and joy were no different from pain and pleasure, fevers and chills, hunger and satiety. All these were distinguished by how qi flowed or didn’t flow, where it stagnated and accumulated or bypassed or failed to stream. Classical medicine had developed an array of techniques for controlling this flow, including herbal concoctions, needling, moxibustion, massage and exercise. But, in Chen Shiduo’s world of post-Manchu-invasion China, doctors knew that nothing changed qi’s streaming as forcefully as a sudden surge of feeling. Emotions could cure, because feelings were fluids. Because to feel was to flow.

GLOSSARY

anger nu 怒, big anger danu 大怒, eruptive anger yishi nuqi一時怒氣, extreme anger nu ji 怒极, oppressed anger yunu 鬱怒, raging anger baonu 暴怒

anxiety and grief yubing 鬰病, youchou 忧愁

Chen Shiduo 陳士鐸 (1627–1707)

Cheng Hao 程顥 (1032–1085)

Cheng Yi 程頤 (1033–1107)

five zang wuzang 五臟

frustration and grievance naonu 惱怒

organ zang 臟

phlegm stuck within the heart tan mi xinqiao 痰迷心竅. For more on this concept, see Natalie Köhle's essay, ‘Spirit, Sweat and Qi’, in this volume.

qi 氣

School of Principle 理學

superabundance taiguo 太過

visceral pain: guts being torn asunder chang jie yu duan 腸結欲斷, liver and lungs and liver ripped out ru ku ganfei 如刳肝肺, heart seared in oil xin ruo fengao 心若焚膏

yang 陽

yin 陰

Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200)

IMAGE AND FILM CREDITS

Listed in the order in which they first appear in the essay

Eyes. From Twenty-Five Bust Portraits of Famous Scholars (Ming dynasty). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Rice Culture, or Sowing or Reaping (before 1353). Metropolotian Museum of Art. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Hanging man silhouette. Kuriyama, Hanging Man Silhouette, 2020. Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Ming dynasty scholar. From Twenty-Five Bust Portraits of Famous Scholars (Ming dynasty). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Green landscape. Zhang Hong, Peach Blossom Spring, 1638. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Demons torturing dead. Jin Chushi (late 12th cent.), Ten Kings of Hell, before 1195. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0). Modified by author.

Photograph of ruined buildings. Kuriyama, n.d. Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Hurricane. Taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under Pixabay license. Modified by author.

Inner viscera. Neijing Tu. In Zhang Jiebin (1563–1640), Leijing tuyi, juan 3. Fujikawa Collection, University of Kyoto main library. Free license with attribution. Modified by author.

Ear. Kuriyama, 2020. Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Mooncake. Taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under Pixabay license.

Laughing Buddha. Taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under Pixabay license.

Surging waters film. Kuriyama, Surging Waters, 2020. Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

Roiling waters. Kuriyama, Roiling Waters, 2020. Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Chen Shiduo 陳士鐸 (1627–1707). Bianzheng qiwen 辨證奇聞 [Extraordinary Anecdotes of Differentiating Diseases] (1687). The 1763 edition is reprinted in Chen Shiduo yixue quan shu 陳士鐸醫學全書. Edited by Liu Zhanghua 柳長華. Beijing, Zhongguo zhongyiyao chubanshe, 1999. Ctext wiki.

Chen Shiduo. Shishi milu 石室秘錄 [Hidden Records from the Stone Chamber] (Preface 1689). Facsimile edition from Xuanyongtang 萱永堂, print edition (1730). In Chen Shiduo yixue quan shu 陳士鐸醫學全書. Edited by Liu Zhanghua 柳長華, et al. Beijing, Zhongguo zhongyiyao chubanshe, 1999. Ctext.

Cheng Shide 程士徳, et al. Suwen zhushi huicui 素問注释匯粹 [The Compiled and Annotated Basic Questions]. Beijing, Renmin weisheng chubanshe, 1982.

Wang Xiuchu 王秀楚. Yangzhou shi ri ji 揚州十日記 [Account of Ten Days of Yangzhou] (1645). Printed in Japan in 1835. Reprinted in Zhongguo neiluan waihuo lishi congshu 中國內亂外禍歷史叢書. Edited by Xia Yunyi 夏允彜. Taibei: Guangwen shuju, 2012.

Secondary Sources

Kuriyama, Shigehisa. ‘Angry Women and the Evolution of Chinese Medicine’, In National Healths: Gender, Sexuality and Health in a Crosscultural Context, edited by Michael Worton and Nana Wilson-Tagoe, 179–89. London: UCL Press, 2004.

Messner, Angelika C. Zirkulierende Leidenschaft. Eine Geschichte der Gefühle im China des 17. Jahrhunderts [Circulating Passions: A History of Emotions in 17th-Century China]. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag, 2016. doi.org/10.7788/9783412504922

Messner, Angelika C. ‘Knowing and Doing Emotions in Times of Crisis and Radical Change’. L’Atelier du Centre de recherches historiques, Revue électronique du C.R.H. (École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales) 16 (2016): 1–18. doi.org/10.4000/acrh.6736

Messner, Angelika C. ‘Towards a History of the Corporeal Dimensions of Emotions: The Case of Pain’. Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques LXVI 4 (2013): 943–72.

Messner, Angelika C. ‘Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China. Editor's Introduction to the Thematic Section’. Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques LXVI 4 (2013): 893–913.

This essay should be referenced as: Angelika C. Messner and Shigehisa Kuriyama, ‘Fluid Feelings’. In Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body, edited by Natalie Köhle and Shigehisa Kuriyama. Asian Studies Monograph Series 14. Canberra, ANU Press, 2020. doi.org/10.22459/FM.2020

MORE FLUID TALES

Introduction

1. Manipulating Flow

Fluid Feelings

Angelika C. Messner and

Shigehisa Kuriyama