sunk from sight

mapping the fluid body

It felt soft. Or was it slippery? Maybe it felt more like sand. No, not like sand. More like sand soaked in rain.{{1}}{{{Expressing haptic knowledge often involved analogies like ‘sawing a bamboo’ or ‘rain-soaked sand’. Shigehisa Kuriyama has shown the ways in which different conventions of seeing, feeling and naming have generated a broad taxonomy of mo characteristics. These types were by no means stable. As ephemeral objects, they contributed to what Kuriyama describes as the ‘fragility of haptic knowledge’. See Shigehisa Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (New York: Zone Books, 2002), 65. On the tactile experiences of the body in early forms of medicine in China, see Elisabeth Hsu, Pulse Diagnosis in Early Chinese Medicine: The Telling Touch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).}}}

The mo 脈—also known as mai, luo, vessels, channels, tracts and meridians—express texture and time.{{2}}{{{This is in reference to the longer historiography of how scholars have engaged with translating mo 脈. For instance, Vivienne Lo has offered mo as ‘channels’ in contrast to Paul Unschuld’s ‘conduits’, Nathan Sivin’s ‘tracts’ and Donald Harper’s ‘vessels’. See Vivienne Lo, ‘Imagining Practice: Sense and Sensuality in Early Chinese Medical Illustration’, in Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft, ed. Francesca Bray Dorofeeva-Lichtmann and Georges Métailié (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 383–424; Paul Unschuld, Medicine in China: A History of Ideas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010); Nathan Sivin, Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies, 1987); Donald Harper, Early Chinese Medical Literature (London: Routledge, 2015).}}}

Though they appear like static lines on the body beneath this text, mo are objects in motion.{{3}}{{{Here, I recognise the unresolved issues in referencing ‘a’ body or ‘the’ body. Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Margaret Lock have urged that references to representations of a ‘body’ can be to an individual body if readers see themselves in the images at hand; they can also be ‘social’ bodies when illustrators copy and distribute drawings; they can also easily turn into a ‘body politic’ in the case of early Daoist texts that inscribe social hierarchies directly onto body maps. As Caroline Bynum put it, the ‘lack of limits’ on the body, a body and my body engender a rich discussion of bodies in earlier literature in gender studies. In the case of Fluid Matter(s), these boundless limits can be further applied to frame comparative medical theories. See Scheper-Hughes and Lock, ‘The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology’, Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1987): 6–41; Bynum, ‘Why All the Fuss about the Body? A Medievalist’s Perspective’, Critical Inquiry 22, no. 1 (1995): 5.}}} Texture and time, then, have technical terms. Mo sometimes can feel ‘rough’, ‘gentle’, ‘heavy’, ‘tight’ or ‘slippery’. Other times they could be ‘slow’, ‘delayed’ or ‘fast’.

These technical terms worked as diagnostic tools. Mo extended to different depths of the body and occasionally reached the skin. A practised hand could press into the mo on the wrist and access its buried textures. These textures transmitted the state of internal organs. Mo communicated these textures and brought them to the surface, crossing the boundaries of a seemingly solid body.

basic distortions

Historians and anthropologists have long engaged with the expressions, transformations and secrets that conspired beneath the skin.{{4}}{{{Barbara Duden’s study of eighteenth-century German case histories has shown how these internal collusions were by no means self-evident, while numerous histories of embalming and dissection have demonstrated how cutting into, and opening up, bodies was a largely gendered practice. See Barbara Duden, The Woman Beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998); Katharine Park, Secrets Of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2010).}}} Yet, the history of fixing unseen movements onto the page remains under-explored.{{5}}{{{Some of the more recent scholarship on body maps include Vivienne Lo’s marvellous collection of essays on graphic images and Catherine Despeux’s analysis of Daoist imagery. See Vivienne Lo and Penelope Barrett, Imagining Chinese Medicine, Sir Henry Wellcome Asian Series, vol. 18 (Leiden: Brill, 2018); Catherine Despeux, Taoism and Self Knowledge: The Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection (Leiden: Brill, 2018).}}} Notwithstanding the abundance of maps and the scores of lines and dots that show mo in motion, less work has been done to understand body mapping as a kind of cartographic practice.

But how is fixing the body on paper a kind of cartographic practice? Physicians can measure your height, but rarely do they bother measuring the length of your arm, the width of your hips or the distance between your cheekbones. However, these measurements mattered to the illustrators who created images of individual mo. Classical treatises that named the distance between body parts allowed readers to use their own judgement. Practitioners knew that mo could move. Mapping the fluid body was hard work because fluids flowed. Even when books identified the location of therapeutic sites, those sites could drift.

This is not to reify geographic cartography as a more ‘accurate’ science. The Earth’s surface was also hard to map. In the history of cartography, astronomers tried to measure the size of the world at the end of the eighteenth century right when the French Government was under siege. Undeterred, the partially blind Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre and his collaborator Pierre-François-André Méchain tried to map the world. They started by measuring France. The two men climbed up abandoned churches and calculated their proximity to other towers. With a Borda repeating circle in hand, they triangulated these distances to measure a fraction of the meridian arc, which would help to determine a course from the north pole to the equator that, when further divided, would produce a perfect metre.{{6}}{{{Ken Alder’s close study of Delambre and Méchain’s baffling field notes has demonstrated how political chaos disrupted the already maddening task of trying to measure distances. Ken Alder, The Measure of All Things: The Seven-Year Odyssey and Hidden Error That Transformed the World (New York: Free Press, 2003).}}}

Delambre and Méchain’s project failed. The three-dimensional landscape resisted translation into two dimensions. The dipping valleys, sliding mounds of silt, fallen trees and local villagers all interfered with the astronomers’ plans. People moved. Dirt moved. Too many things fell out of place.

Still, maps remained a robust graphic category. Practised cartographers knew that maps promised a great deal. They promised to filter noise, to bring clarity despite an overabundance of information, and to naturalise unfamiliar places, spaces and things. Maps could be read literally, even when literal representations required many levels of distortion. Maps marked sites that were ‘there’ without committing to the place itself. Distortions were not accidental. They were necessary.{{7}}{{{See Dava Sobel’s history of mapping longitude, Mark Monmonier’s pithy How to Lie with Maps, Bill Rankin’s layered account of the GPS and Anthony Acciavatti’s mapping of the Ganges river. Dava Sobel, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (New York: Walker Books, 1995); Mark Monmonier, How to Lie with Maps (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Anthony Acciavatti, Ganges Water Machine: Designing New India’s Ancient River (San Francisco: Applied Research & Design, 2015).}}}

When it came to body maps, lines and dots also appeared oddly domesticated on paper. Authors would compensate for schematic woodcut prints by filling the images with text. They explained that the lengths and distances of the mo of large, small, old, and young bodies differs. Bodies were idiosyncratic. Maps were idealised. But were they still useful as epistemic tools?

Maps presented a mathematical puzzle. They projected a three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional surface using one-dimensional signs. These were the limits of maps as a graphic category. They told one version of the truth—a partial representation from a perspective of totality.{{8}}{{{This asymmetrical projection of surfaces also applies to frictions in translation, which I describe in more detail in my forthcoming book. See Lan A. Li, Body Maps: Meridians and Nerves in Global Chinese Medicine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).}}} Maps confined the imagination to signs on a page fixing things in constant motion.

paper rivers

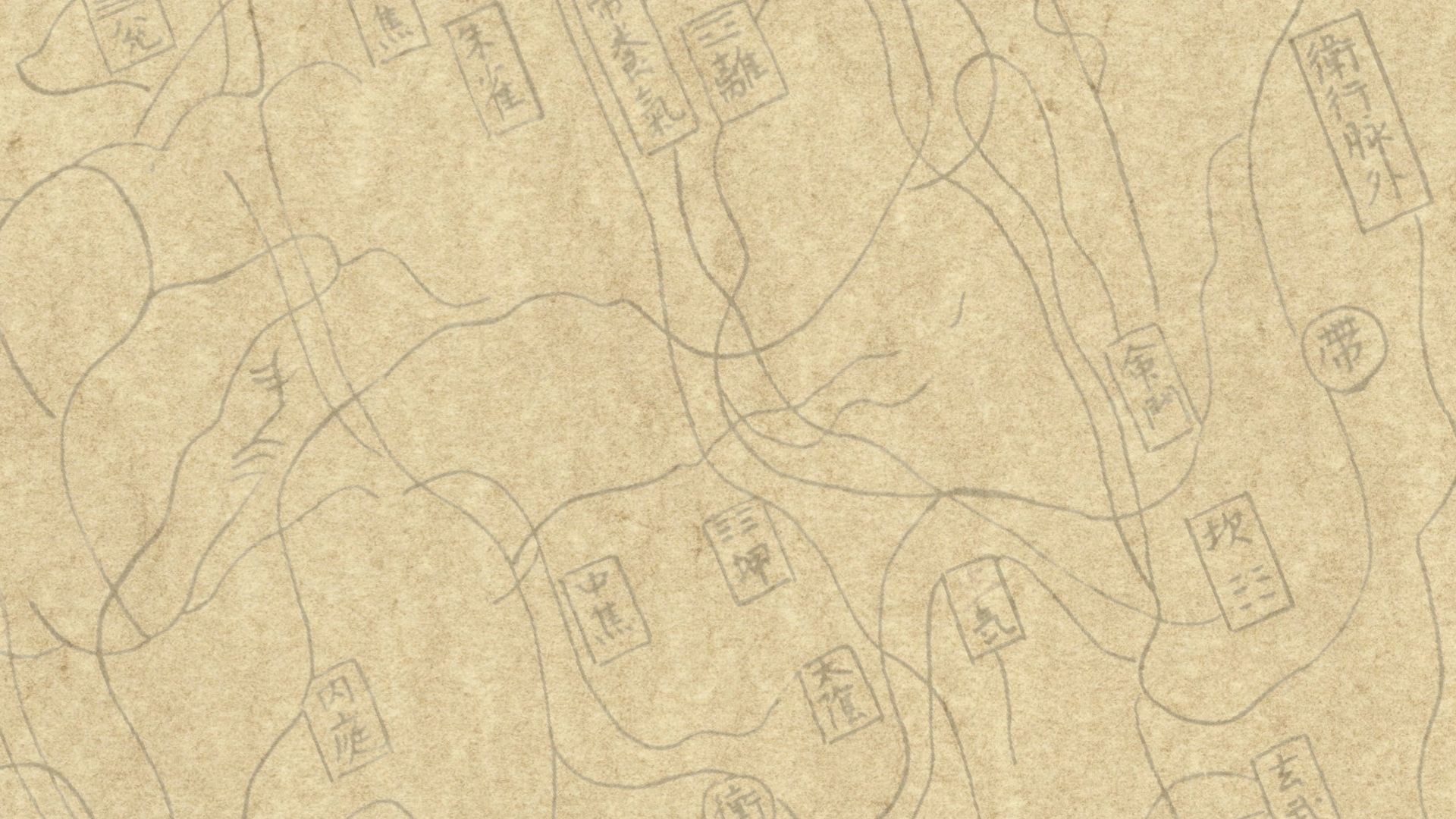

Not all diagrams that looked like maps functioned like maps. On paper, mo appeared as a series of lines and dots.{{9}}{{{On the multiple lives of lines, see Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (London: Routledge, 2011); Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (London: Routledge, 2016). Scholars have offered social histories of the abundance of lines used to depict human movement during the fin de siècle. See, for example, Robert Brain, The Pulse of Modernism: Physiological Aesthetics in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016). Less work has been done on the ambiguity of lines in depicting fluid structures in the body.}}} These lines did not reveal the exact location of the mo, but instead invited the reader to imagine where they could travel and how they might behave. More importantly, representations of mo came in what has been commonly known in East Asia as tu 圖. Tu was a special graphic genre that could look like a map, but was not just a map. Unlike Delambre and Méchain’s drawings that limited a reader’s spatial imagination, tu moved the mind.

Best elaborated in the edited volume Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China, tu was a special category of visualisation that portrayed technical knowledge.{{10}}{{{Francesca Bray, Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann and Georges Métailié, Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft (Leiden: Brill, 2007), passim.}}} Tu was different from a painting (hua 畫) and distinct from a likeness (xiang 相).{{11}}{{{Tu is distinct from map; not all maps are tu, for instance, if they come in the form of a painting. For a survey of East Asian cartographic maps, see Nathan Sivin and Gary Ledyard, ‘Introduction to East Asian Cartography’, in Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies, vol. 2, book 2, ed. J. B. Harley and David Woodward (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 23–31; Richard Pegg, Cartographic Traditions in East Asian Maps (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014); Kären Wigen, Sugimoto Fumiko and Cary Karacas, Cartographic Japan: A History in Maps (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).}}} It was a specialist term and a functional category that was not stylistic, but a kind of ‘template for action’. It provoked the reader. It called upon the imagination. It sometimes stood alone, sometimes with text, and often contained written characters. In other words, these inscriptions did not speak for themselves.

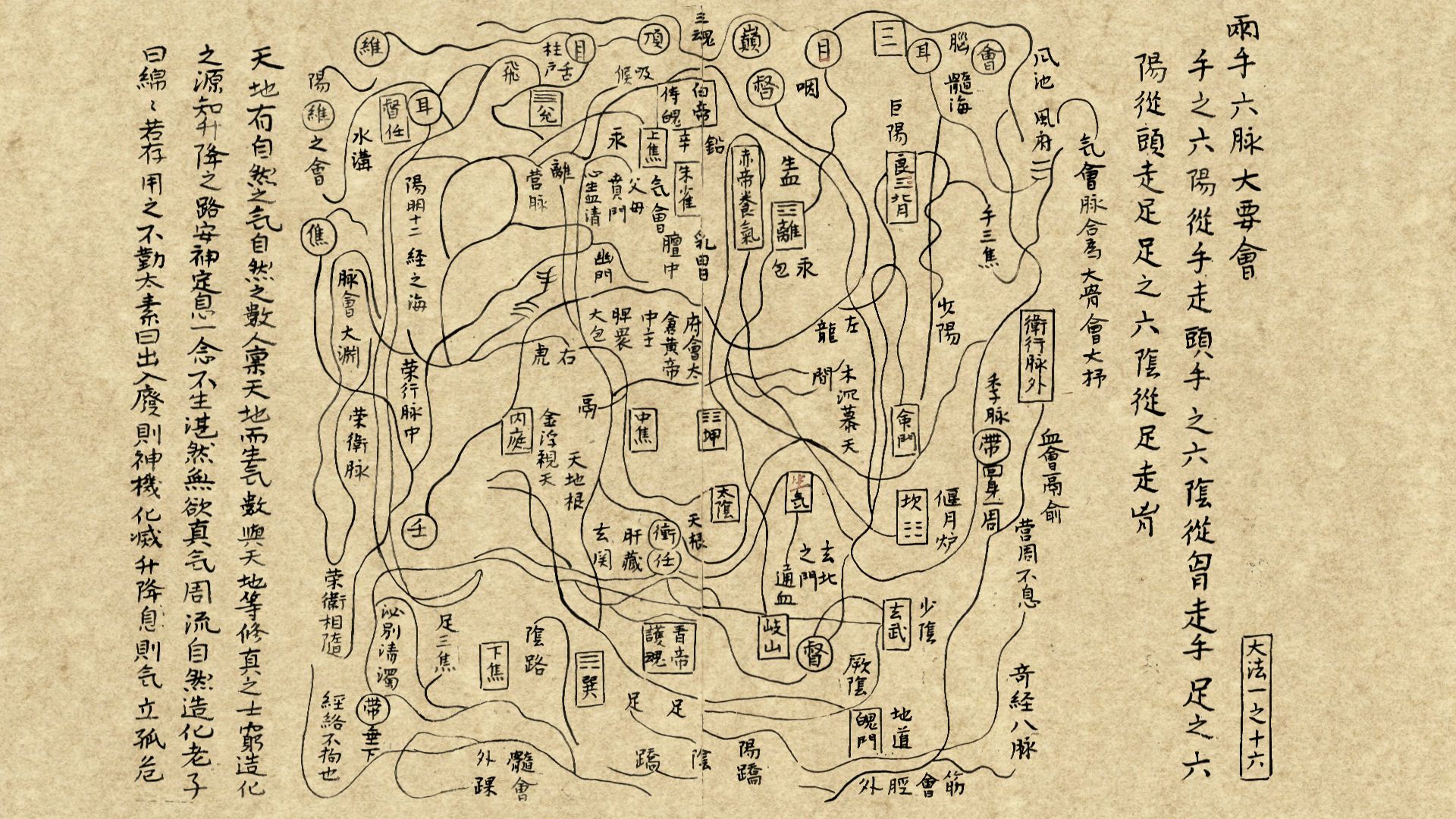

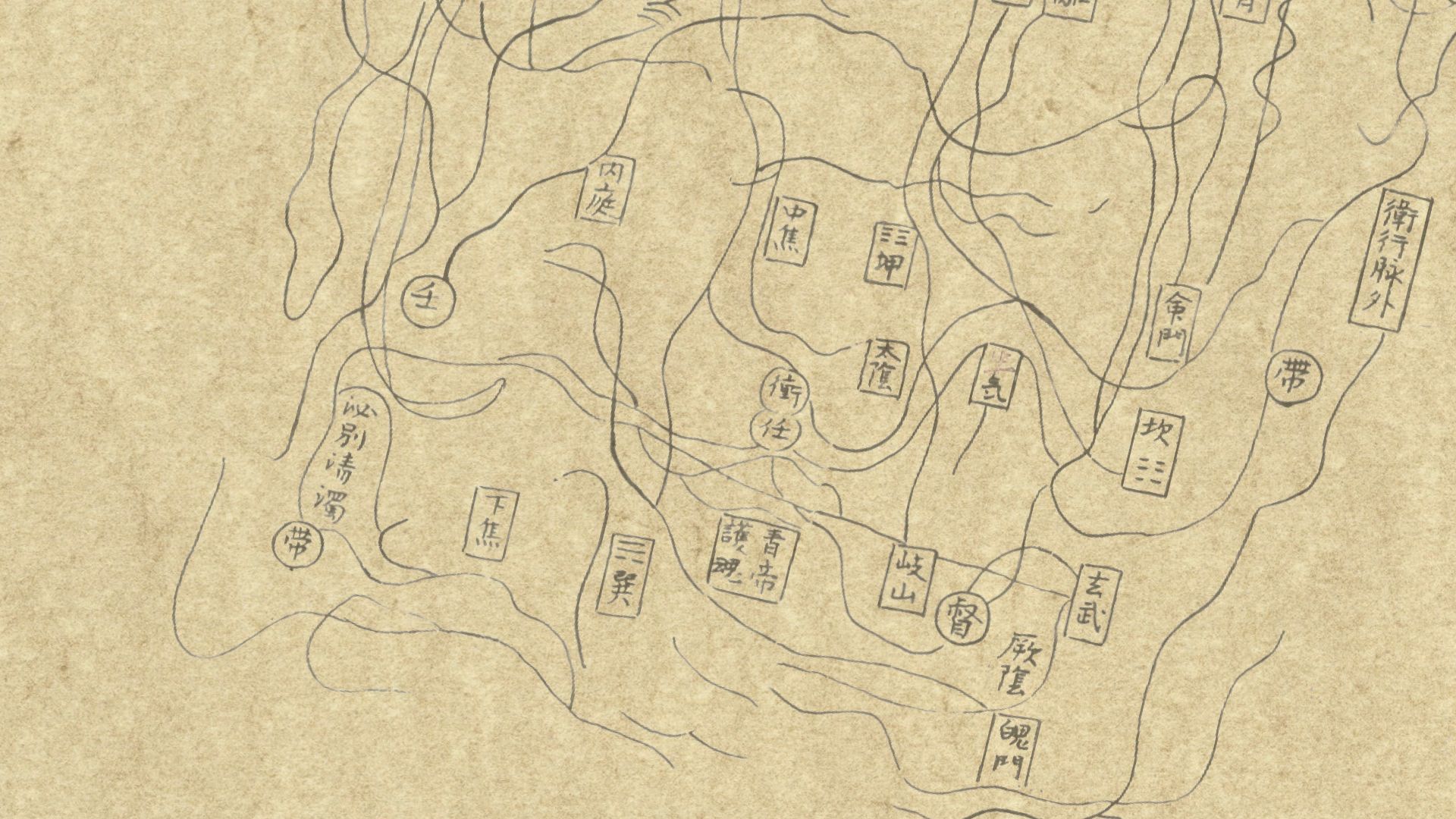

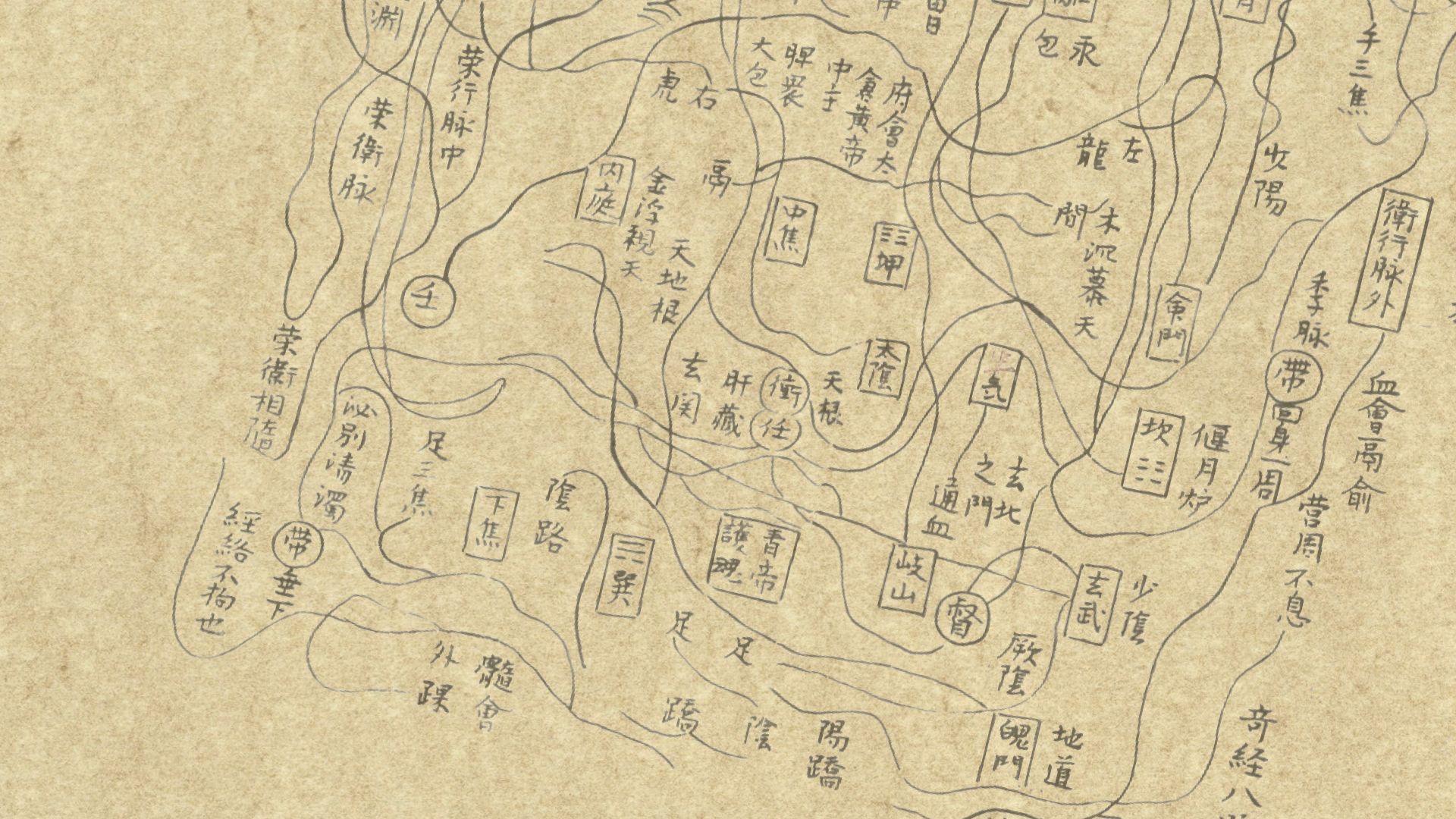

Liang shou liu mo da yao hui 兩手六脈大要會. Anonymous, 1234.

Liang shou liu mo da yao hui 兩手六脈大要會. Anonymous, 1234.

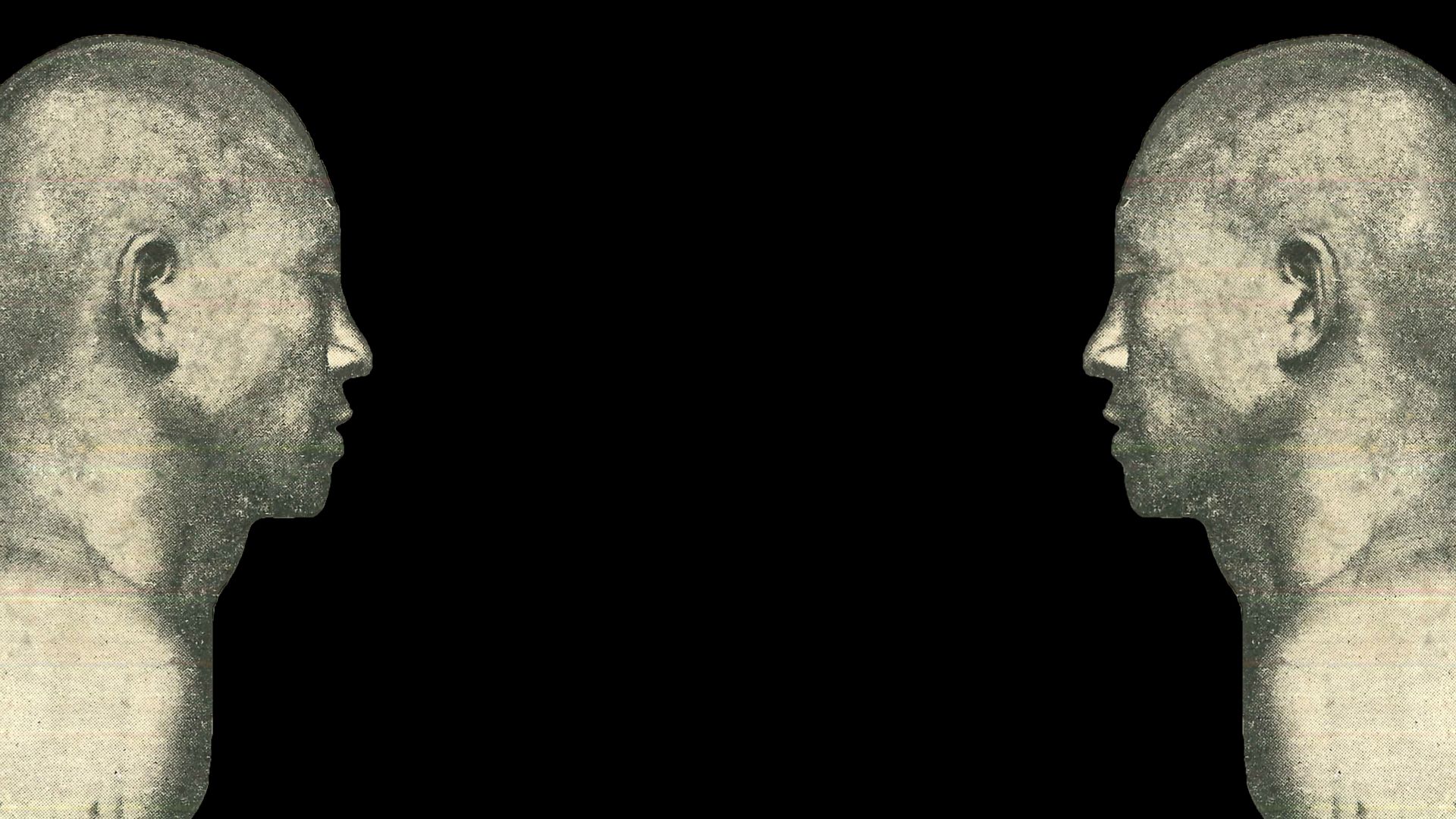

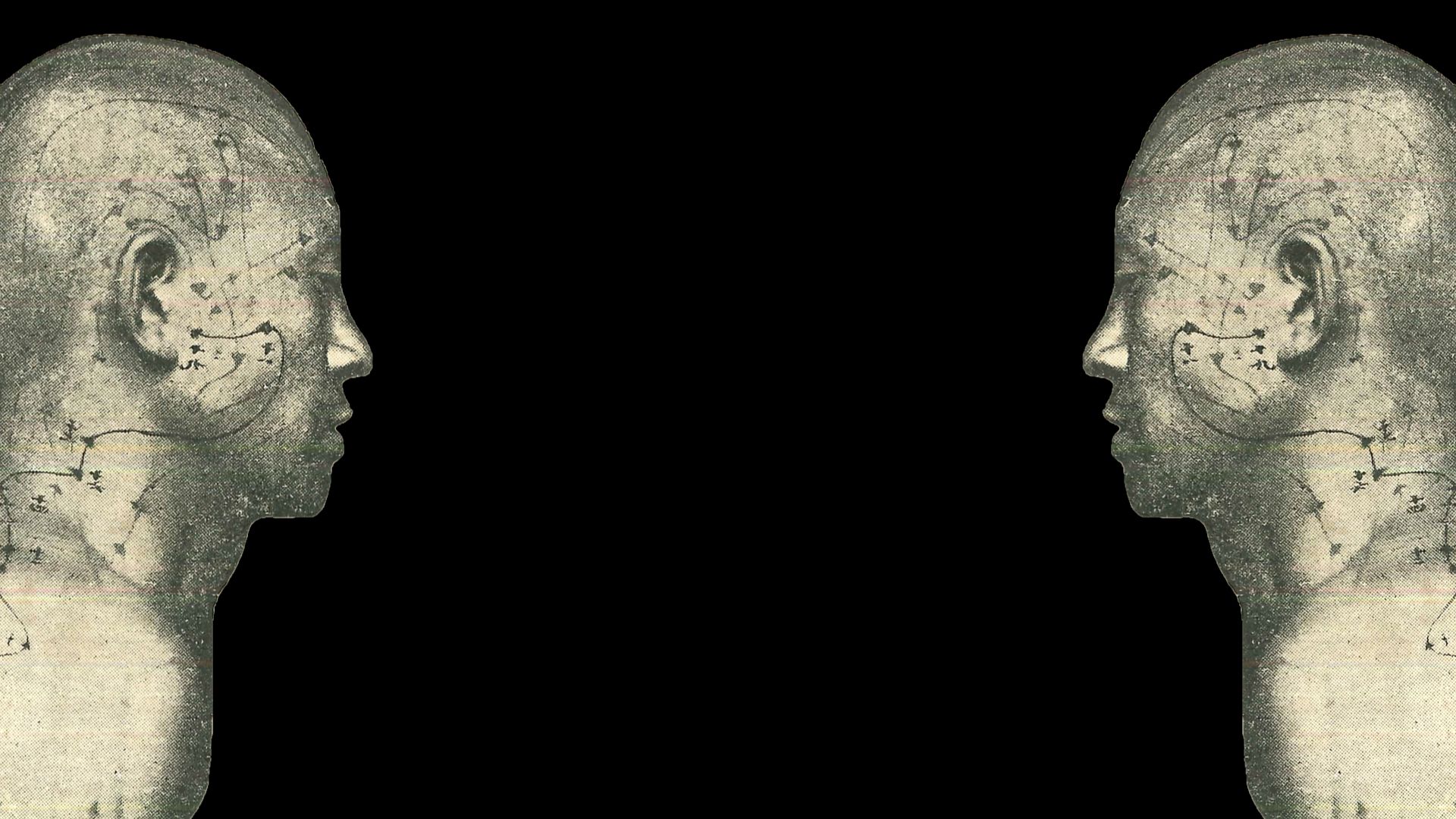

In the genre of tu, text animated the body. Text stretched fluid forms from a static figure on the page to a moving object in the mind.{{12}}{{{Here, I recognise the ‘mind’ as an object that also has fluid-like features, which connects to broader comparative histories of science and medicine.}}} For instance, when the thirteenth-century scholar-physician Wang Haogu (1200–64) illustrated his treatise with his version of the mo, he drew them as twisting and contorting around one another. On the lower right corner of the image, Wang wrote that ‘nourishing qi is circulating without interruption’ yingzhou buxi 營周不息, explaining that streams of vitality were constantly coursing the body.{{13}}{{{For an interpretation of Wang Haogu’s illustrations of the mo as a ‘map of human vitality’, see Shigehisa Kuriyama, ‘The Imagination of the Body and the History of Embodied Experience: The Case of Chinese Views of the Viscera’, in The Imagination of the Body and the History of Bodily Experience, ed. Shigehisa Kuriyama (Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies, 2001), 27.}}}

Wang Haogu understood the utility of tu. Though it is unclear whether he drew this image himself, he was unique to feature it so prominently in his treatise, which he had written with a sense of urgency. By the end of the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Jin dynasty had just collapsed and surveys reported nearly 33 contagious epidemics.{{14}}{{{The record of 33 epidemics was stark in comparison to only one case that was recorded in the eleventh century. See Wenbiao Qiao 乔文彪 and Ting Su 苏婷, 中國歷代名家學術研究叢書:王好古 Zhonguo lidai mingjia xueshu yanjiu congshu, ed. Pan Guijian潘桂娟 (Beijing: China Chinese Medicine Publishing House, 2017), 8.}}} Under these circumstances, it baffled Wang that physicians did not understand the body. ‘Brainless zombies!’ he lamented.{{ 15}}{{{In Wang’s words: ‘嗟乎游魂行尸’, Wang Haogu, quoted in Qiao and Su, 中國歷代名家學術研究叢書:王好古, 4.}}}

Though he did not come from a family of physicians, Wang used his literary background to revisit classic medical texts. He even changed his professional name to Haogu 好古, which meant ‘lover of antiquity’. He also travelled to Hebei, Henan and Beijing to learn from other specialists and expand his knowledge about herbs and materia medica.{{16}}{{{Qiao and Su, 中國歷代名家學術研究叢書:王好古, 11.}}} He concluded that ignorance was born from a failed imagination. ‘You need not seek the magnificent to find it’, the itinerant Wang explained.{{17}}{{{Chinese: 不必重楼幽阙, 明堂绛宫, translated more literally: ‘No need to climb to the highest peaks/palaces/shrines, to seek the heart of the empire’. Wang Haogu, Yi Yin Tang Ye Zhong Jing Guang Wei Dafa, 4.}}}

One needed to use imagination to see moving mo. On the page, mo sometimes appeared skeletal. In one of the most famous representations of therapeutic paths from the early fourteenth century, mo looked like bony structures.{{18}}{{{See Long Huang, Zhongguo Zhenjiu Shi Tujian 中国针灸史图鉴 [Illustrated History of Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion] (Qingdao Publishing, Qingdao, 2003), 67–69.}}} A much more recent genre of tu, the Mingtang tu, which emerged in the Ming-Qing period (1368–1912), drew parallel lines to mark fluid paths. Though historians have interpreted the double tracts as representing vessels, it is also possible that this graphic detail served another purpose. Double lines rendered the mo visually distinct from the ribs, hips, nails, toes, shoulder blades, ears, eyes and kneecaps. They were as physical as these structures, only they could slip out of reach.

Lines on the page represented physical structures that operated across multiple dimensions. They measured movement, texture and distance. Wang Haogu claimed that the ren and du paths, which extended down the chest and up the spine, measured almost nine feet long. The foot Yang meridians were eight feet long regardless of the individual’s ‘actual’ height. These lengths mattered because one meridian connected to the next. And when all of the paths added up to a single loop—as a single path that spanned 862 chi 尺—they measured not only a unit of distance, but also a unit of time.{{19}}{{{When all of the meridians are added together, their combined length is 86 zhang and two chi, or 862 ‘feet’. As a single entity, meridians also counted 880 cycles that measured the length of an evening. Wang Haogu, Yi Yin Tang Ye Zhong Jing Guang Wei Dafa, 32.}}}

Tu remained simple and schematic. The images themselves, though, were immensely complex. They did not pretend to perfectly represent the fluid qualities of moving paths in the body because mo were not fixed to solid surfaces.

Tu offered a schematic guide for the reader’s mind. Authors took them seriously, but did not read them literally. Mo crumpled and twisted, stretched and shrank. With the help of text, mo broke the boundaries of the body and extended beyond its typical features. As a complete set, they stood as permanent entities that expressed texture, marked distance and measured time.

fixed caverns

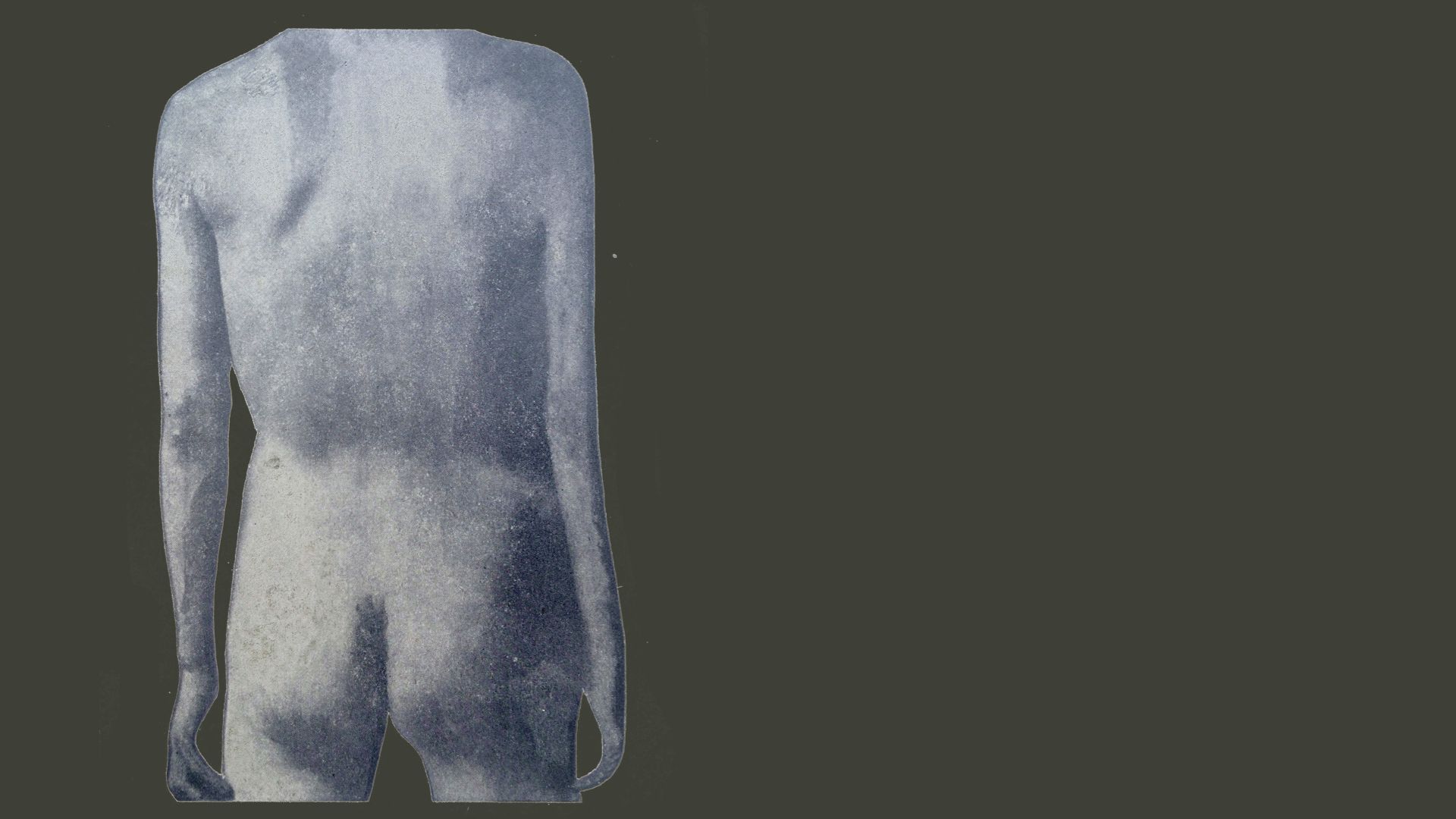

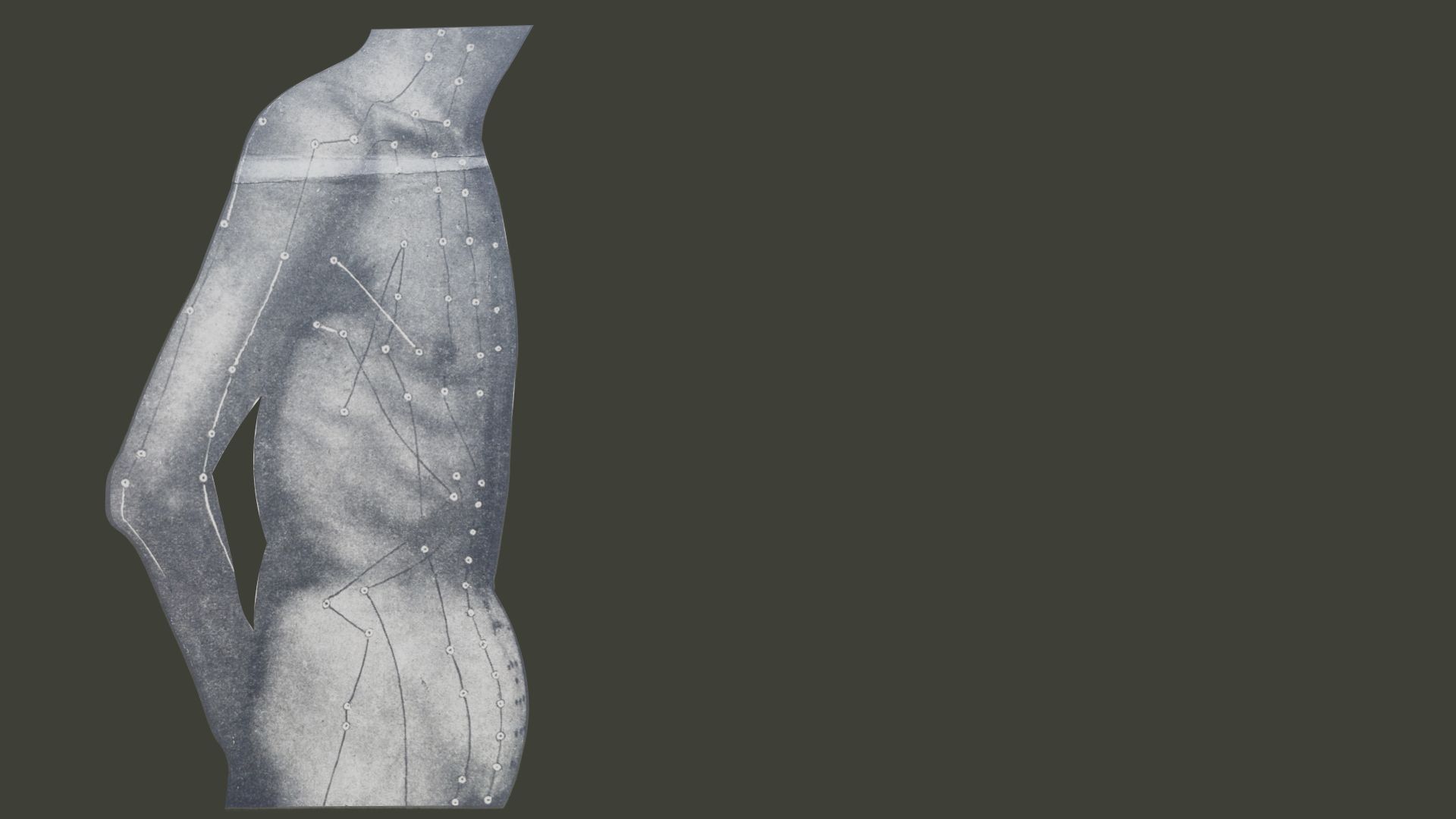

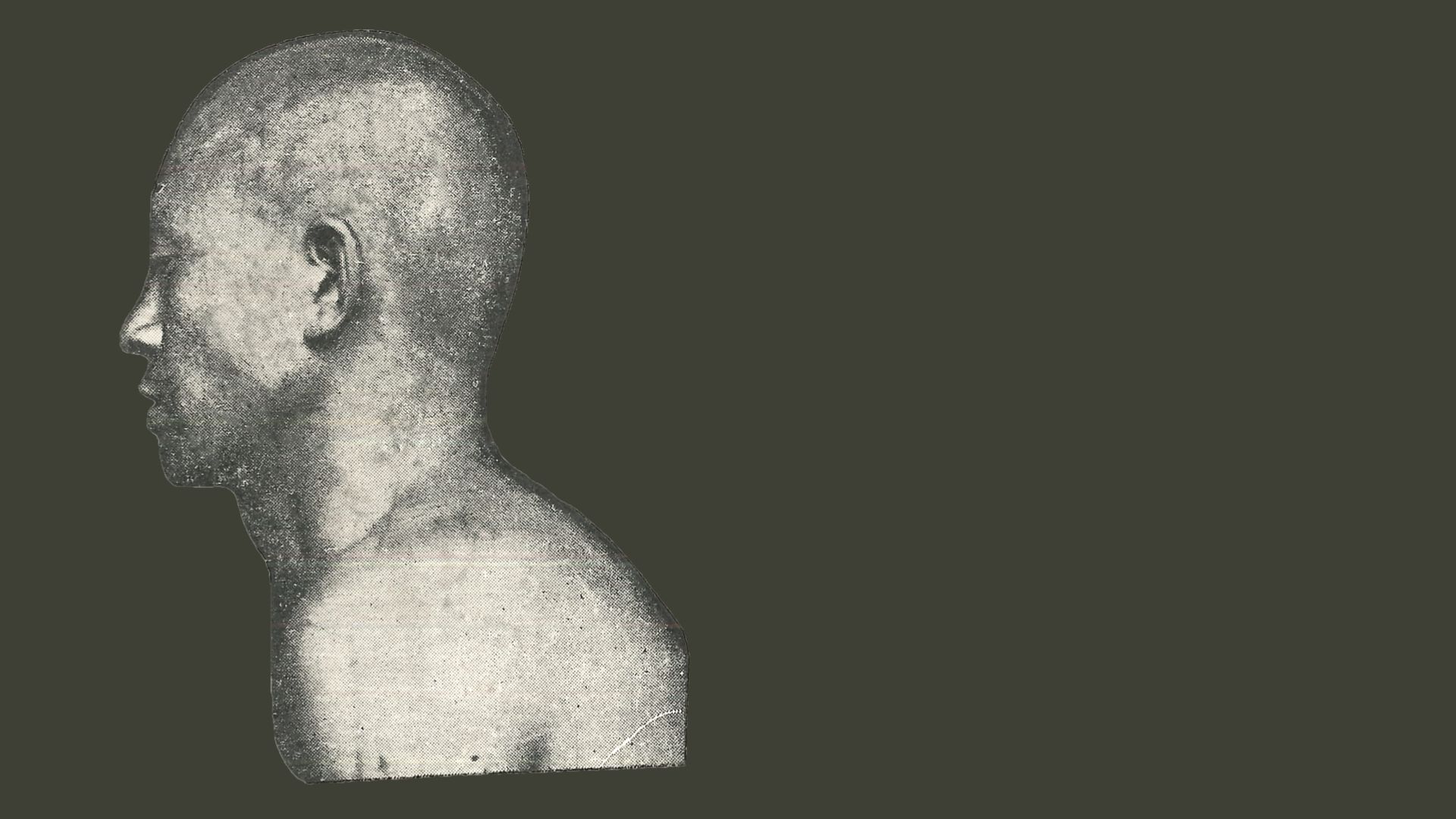

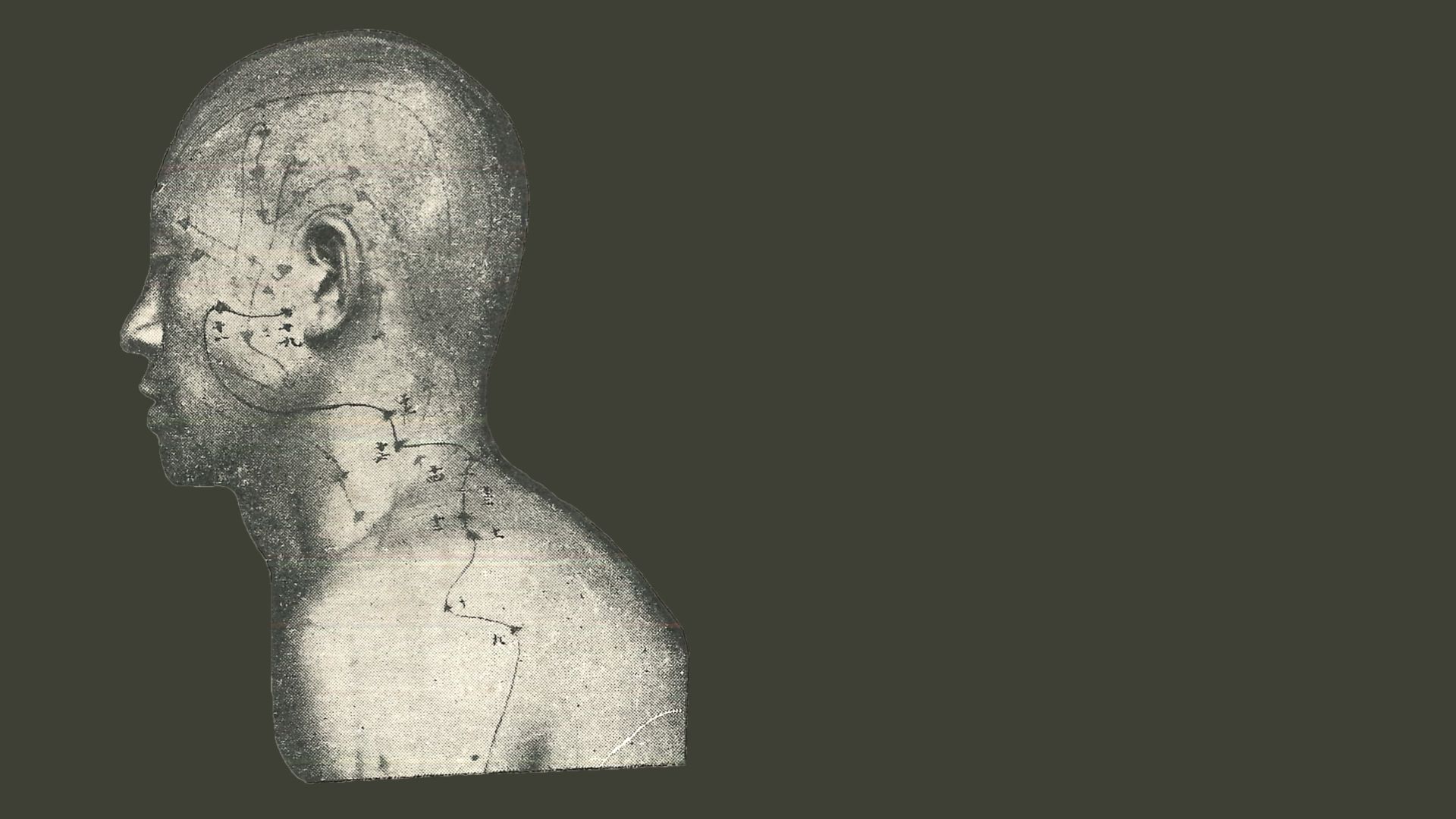

In the early twentieth century, photography introduced another kind of graphic genre. Physicians like the 30-year-old Cheng Dan’an (1899–1957) understood the demand for new modes of representation. Mechanical objectivity could define the modern nation. Republican reformers in Shanghai said so, and Cheng believed them. On a mission to modify classical images of the mo, he acquired a camera and gained access to a studio. He recruited a male model and took pictures of the man’s front, back and side.

This was unusual. Not only because nude models were technically banned in 1926, but also because of Cheng’s mobilisation of visual genres.{{20}}{{{Cameras were introduced to Shanghai markets in 1873, with models from Britain, America, Belgium and Japan. By the late 1920s, the dominant personal camera was Agfa from Germany, often seen in the pages of the municipal newspaper Shenbao, pictured below. Tianping Wang, Shanghai Sheying Shi 上海攝影史 [The History of Photography in Shanghai] (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2012), 14.}}} He used the techniques of full body photography that studio operators had popularised in the early 1890s to take pictures of his medicalised subjects.{{21}}{{{Radical artist Liu Haisu 刘海粟 (1896–1994) famously introduced nude human models for art education in the 1920s, which local officials later banned. For more about this period, see Ken Lum et al., Shanghai Modern 1919–1945, ed. Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker, Kuiyi Shen and Zheng Shengtian. Bilingual edition (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004). Only, his models did not stand contrapposto, lounging or leaning to one side. They posed in kouroi, facing forward with arms hanging on either side, inviting inspection. }}}

Cheng experimented with his pictures. He drew directly onto the photograph and transferred the inscriptions onto thin sheets of rice paper. In a more famous example, he drew directly onto a human body, and took time to press lines and dots into a man’s cheeks, fingers, armpits and inner thighs. Without these modifications, the photograph, or xiang/likeness, did not stand on its own.{{22}}{{{Many terms were invented in the nineteenth century to describe photography, which referenced a kind of portrait painting, such as zhaoxiang 照相, yingxiang 影相 and, finally, sheying 摄影. See Yi Gu, ‘What’s in a Name? Photography and the Reinvention of Visual Truth in China, 1840–1911’, The Art Bulletin 95 (2013): 120–22.}}} By combining photography and drawing, Cheng used the model’s body to build a tu. In this new kind of image, Cheng pinned mo on flesh. There, they did not twist; they did not sink. They definitely did not tell time. He did not use text to explain that the body was a landscape in constant motion. Like the camera, this image fixed objects in place.

‘Previous bodies were [drawn] in two dimensions’, Cheng observed: ‘This encouraged inaccuracy.’{{23}}{{{In the original text, Cheng wrote: ‘前人穴图。悉属平面。绝不准确。鍼术之不进步。良由于此。因是力矫其弊。点穴人身而摄影之。学者可以一索即得矣’. Or, roughly: ‘Previous tu of sites [were] all presented on a flat surface. This was completely incorrect and directly hindered the development of needling techniques. Thus, it is hard to correct for this problem. Locating a site on the person and directly capturing with photography allows the reader to easily/accurately find the site.’ Cheng Dan‘an, Jianyi Jiuzhi (Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 2016), 36.}}} For Cheng, the camera served as a tool for precision. Like a map, it promised a lot. It promised clarity. It placed sites in context. It disciplined the mo. But, despite these promises, the photograph was stuck in two dimensions. Even worse, the bodies of Cheng’s male recruits did not apply to everyone. The curve of their belly and the dip in their collar bone applied to them alone. Rather than stabilising the objective mechanical gaze, the camera only highlighted an individual’s idiosyncrasies.

No title. Cheng Dan’an, 1955.

No title. Cheng Dan’an, 1955.

Years later, Cheng would abandon photography. The more he worked with patients, the more he recognised the importance of individual case histories. No longer occupied by the promises of photography, he roughly drew individual portraits of individual people. Their faces connected to cases of nasal congestion, pertussis, asthma, haemoptysis, pneumonia, hypertension, pleurisy, cholelithiasis, colitis, cholera, cecal enteritis, bloody defecation, diabetes, insomnia, beriberi, malaria, epilepsy, nosebleeds, polyps, tonsillitis, diphtheria, blood clotting, leucorrhea paediatric meningitis and facial nerve palsy.{{24}}{{{These images were originally drawn on wax paper and published towards the end of Cheng’s life. Reprints of Cheng’s clinical notes were published as Cheng, Jianyi Jiuzhi 针灸简易 [Moxibustion Simplified].}}}

Cheng no longer invested in the promise of mechanical accuracy. Instead, he relied on pen and paper to approximate people and their individual grievances. The dozens of faces conveyed a different kind of accuracy that joined the importance of imagination found in tu with the impulse for precision that came with experience. He had learned that photographs of a naked body also reinforced its physical boundaries. Layering lines onto people and paper brought together the objective expectations of maps and the dynamic qualities of tu. On this surface, mo could not leave the skin.

When physicians and illustrators copied, traced and invented new body maps, they increasingly found that old technologies of hand-drawn images exceeded the abundance of detail offered by photographs and fluorescent dyes. However impressive, these tools still could not visualise mo in full, at once.

Fluid bodies interrupted dreams of accuracy. When illustrating mo paths, the body demanded different forms of measurement. It required flexible means of measurement that could follow flexible paths in the body. These paths communicated different tactile experiences. They expressed different textures and told time. They represented fluid matter that hid beneath the skin. There, they sunk from sight.

GLOSSARY

Cheng Dan’an 承淡安 (1899–1957)—early twentieth-century physician credited for reforming acu-moxa education in Republican and Communist China.

chi 尺—known as the ‘same body inch’ developed by the seventh-century physician Sun Simiao 孫思邈 (618–907) as a means for standardising body measurements.

du mai 督脈—also known as the ‘governing vessel’, is related to the Yang meridians and travels down the middle of the back where it connects to the ren mai 任脈 at the top of the head and base of the torso.

hua 畫—a painting

mingtang tu 明堂圖—a heterogeneous class of meridian maps roughly dated to the fourteenth century and usually paired with illustrations of the viscera known as neijing tu (neijing tu 內景圖).

mo/mai 脈—historiographically translated as vessels, channels and tracts, is central to diagnostic and therapeutic practices in acupuncture and moxibustion.

ren mai 任脈—also known as the ‘conception vessel’, is related to the Yin meridians and travels down the front of the body where it connects to the du mai 督脈 at the top of the head and base of the torso.

tu 圖—a graphic category unique to East Asian sources that defined technical diagrams. Though historically distinct from painting and realistic likeness, tu in its contemporary use often refers more broadly to ‘images’ and ‘figures’.

Wang Haogu 王好古 (1200–64?)—a thirteenth-century scholar-physician associated with early images of the viscera in Chinese medicine.

xiang 相—a graphic category associated with photography and other realistic likenesses. The antithesis of tu 圖.

ying qi 營氣—nutritive qi. This is the qi that is derived from food during the process of digestion. It courses throughout the body in the mo, providing essential nourishment.

IMAGE AND FILM CREDITS

Listed in the order in which they first appear in the essay.

Grey line. Image taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under a Pixabay License. Modified by author.

Meridian model man 1. Cheng Dan’an, no title, 1933. In Cheng Dan’an, Zengding Zhongguo Zhenjiu Zhiliao Xue, 1933. Public domain. Modified by author.

Reflection. Lisa Limarzi, Water Reflection, 2005. Lisa Limarzi © 2005. Image taken from Flickr. Reproduced under a Creative Common Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivates Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Modified by author.

Bokeh. Fredfunky, Bokeh dans la nuit, 2014. Fredfunky © 2014. Image taken from Flickr. Reproduced under a Creative Common Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivates Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Modified by author.

Hemispheric map. Hubert Jaillot, Atlas Nouveau, 1691. Taken from Wikpedia.org. Public domain. Modified by author.

Repeating circle. Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre, Cercle répétiteur en position pour observations azimutales’, 1807. In BnF Gallica, Illustration de l’ouvrage. Taken from Wikipedia.org. Public domain. Modified by author.

Delambre. Lan Li, Delambre, 2019. Lan Li © 2019.

Body Tu. Anonymous, Liang shou liu mo da yao hui 兩手六脈大要會, original date 1234. In Wang Haogu 王好古 (1200–64?), Yi Yin Tang Ye Zhong Jing Guang Wei Dafa 伊尹湯液仲景廣爲大法, 1234. Edo (1603–1868) reprint. Made available by the National Archives of Japan. Public domain.

Mingtang tu. Anonymous, Cheng-jen Ming-t'ang t'u 正人明堂圖, c. 1601. Wellcome Collection. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution International (CC BY 4.0). Modified by author.

Agfa camera. Advertisement, 1933. In Shenbao 申報 (1933). Public domain. Modified by author.

Model meridian man 2. Cheng Dan’an, no title, n.d. © Hunan Museum of Acupuncture Moxibustion Archives. Reproduced by permission of the archive. Modified by author.

Meridian model man 3. Cheng Dan’an, 1933. In Cheng Dan’an, Zending Zhongguo Zhenjiu Zhiliao Xue 怎定中國針灸治療學 (1933). Public domain. Modified by author.

Patient faces. Cheng Dan’an, no title, 1955. In Cheng Dan’an, Jianyi Jiuzhi 簡易灸治, 1955. Jiangsu: Jiangsu Provincial Health Department 江苏省卫生厅印, 1957. Public domain. Modified by author.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Cheng, Dan‘an 承淡安 (1899–1957). Jianyi Jiuzhi danfang zhiliao ji 簡易灸治·丹方治療集, ed. Chen Biliu 陳壁琉 and Xu Xinian徐惜年 Shanghai Science and Technology Press, Shanghai, 2016.

Cheng, Dan‘an. Zending Zhongguo Zhenjiu Zhiliso Xue 怎定中國針灸治療學 [Validating Chinese Acupuncture Moxibustion]. China Society of Acupuncture Moxibustion Research, Shanghai, 1933.

Wang, Haogu 王好古(1200–64?). Yi Yin Tang Ye Zhong Jing Guang Wei Dafa 伊尹湯液仲景廣爲大法 [Theories of Materia Medica Developed from Grand Methods by Zhong Jing and Derived from Yi Yin] (1234). Edo period (1603-1868) manuscript. Made available by the National Archives of Japan. Public domain.

Secondary Sources

Acciavatti, Anthony. Ganges Water Machine: Designing New India’s Ancient River. San Francisco: Applied Research & Design, 2015.

Alder, Ken. The Measure of All Things: The Seven-Year Odyssey and Hidden Error That Transformed the World. New York, Free Press, 2003.

Brain, Robert. The Pulse of Modernism: Physiological Aesthetics in Fin-de-Siècle Europe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016.

Bray, Francesca, Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann and Georges Métailié, eds. Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft. Sinica Leidensia, vol. 79. Leiden: Brill, 2007. doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004160637.i-772

Bynum, Caroline. ‘Why All the Fuss about the Body? A Medievalist’s Perspective’. Critical Inquiry 22, no. 1 (1995): 1–33. doi.org/10.1086/448780

Despeux, Catherine. Taoism and Self Knowledge: The Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection. Leiden: Brill, 2018. doi.org/10.1163/9789004383456

Duden, Barbara. The Woman Beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Gu, Yi. ‘What’s in a Name? Photography and the Reinvention of Visual Truth in China, 1840–1911’. The Art Bulletin 95 (2013): 120–38. doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2013.10786109

Harley, J.B. and David Woodward eds. Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies, The History of Cartography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Harper, Donald. Early Chinese Medical Literature. London: Routledge, 2015.

Hsu, Elizabeth. Pulse Diagnosis in Early Chinese Medicine: The Telling Touch. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010.

Huang, Long. Zhongguo Zhenjiu Shi Tujian 中國針灸圖鑒 [Illustrated History of Chinese Acupucture and Moxibustion]. Qingdao Pjianublishing, Qingdao, 2003.

Ingold, Tim. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge, 2011. doi.org/10.4324/9780203818336

Ingold, Tim. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge, 2016. doi.org/10.4324/9781315625324

Kuriyama, Shigehisa. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. New York: Zone Books, 2002.

Kuriyama, Shigehisa. ‘The Imagination of the Body and the History of Embodied Experience: The Case of Chinese Views of the Viscera’. In The Imagination of the Body and the History of Bodily Experience, edited by Shigehisa Kuriyama, 17–29. Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies, 2001.

Li, Lan A. Body Maps: Meridians and Nerves in Global Chinese Medicine. Chicago: Chicago University Press, forthcoming.

Lo, Vivienne. ‘Imagining Practice: Sense and Sensuality in Early Chinese Medical Illustration’. In Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft, edited by Francesca Bray, Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann and Georges Métailié, 383–424. Leiden: Brill, 2007. doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004160637.i-772

Lo, Vivienne and Penelope Barrett. Imagining Chinese Medicine. Sir Henry Wellcome Asian Series, vol. 18. Leiden: Brill, 2018. doi.org/10.1163/9789004366183

Lum, Ken, David Clarke, Xu Hong, Xu Jian, Zhang Qing, Michael Sullivan, Shui Tianzhong, et al. Shanghai Modern 1919-1945. Edited by Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker, Kuiyi Shen and Zheng Shengtian. Bilingual edition. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004.

Monmonier, Mark. How to Lie with Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226029009.001.0001

Park, Katherine. Secrets Of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. New York: Zone Books, 2010.

Pegg, Richard. Cartographic Traditions in East Asian Maps. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014.

Qiao, Wenbiao 乔文彪 and Ting Su 苏婷. 中國歷代名家學術研究叢書:王好古 Zhonguo lidai mingjia xueshu yanjiu congshu: Wang Haogu [Academic Research Series of Famous Doctors of Traditional Chinese Medicine through the Ages: Wang Haogu]. Edited by Pan Guijuan 潘桂娟. Beijing: China Chinese Medicine Publishing House, 2017.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy and Margaret M. Lock. ‘The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1987): 6–41. doi.org/10.1525/maq.1987.1.1.02a00020

Sivin, Nathan. Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies, 1987. doi.org/10.3998/mpub.19942

Sivin, Nathan and Gary Ledyard. ‘Introduction to East Asian Cartography’. In Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies, vol. 2, book 2, edited by J. B. Harley and David Woodward, 23–31. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Sobel, Dava. Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time. New York: Walker Books, 1995.

Svenson, Arne and Laura Lindgren. Hidden Treasure: The National Library of Medicine. Edited by Michael Sappol. New York: Blast Books, 2012.

Unschuld, Paul. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Wang, Tianping. Shanghai Sheying Shi 上海攝影史 [The History of Photography in Shanghai]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2012.

Wigen, Kären, Sugimoto Fumiko and Cary Karacas, eds. Cartographic Japan: A History in Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

This essay should be referenced as: Lan Li, ‘Sunk from Sight: Mapping the Fluid Body’. In Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body, edited by Natalie Köhle and Shigehisa Kuriyama. Asian Studies Monograph Series 14. Canberra, ANU Press, 2020. doi.org/10.22459/FM.2020

MORE FLUID TALES

Introduction

1. Manipulating Flow

2. Incorporating Flow

3. Structuring Flow

Sunk from Sight

Lan A. Li