Whose Life is Water,

Whose Food is Blood

Fluid Bodies in Āyurvedic Leech Therapy

Lisa Allette Brooks

Substance (dravya): fluid

Blood is a fluid. Fluids flow. When obstructed, blood accumulates.

The leech squirms in the physician’s gloved hand. Approaching the lower-leg ulcer patient on the treatment table, the physician orients the leech’s mouth to the ulcer’s left margin. Probing the area, the leech bites. The physician removes the gauze and the leech lengthens towards the table. A few seconds later, the leech releases and begins to probe down the ulcer. For a moment, the leech assumes a horseshoe posture, appearing to bite, and then retracts, thickening.

The leech releases and is on the move again.

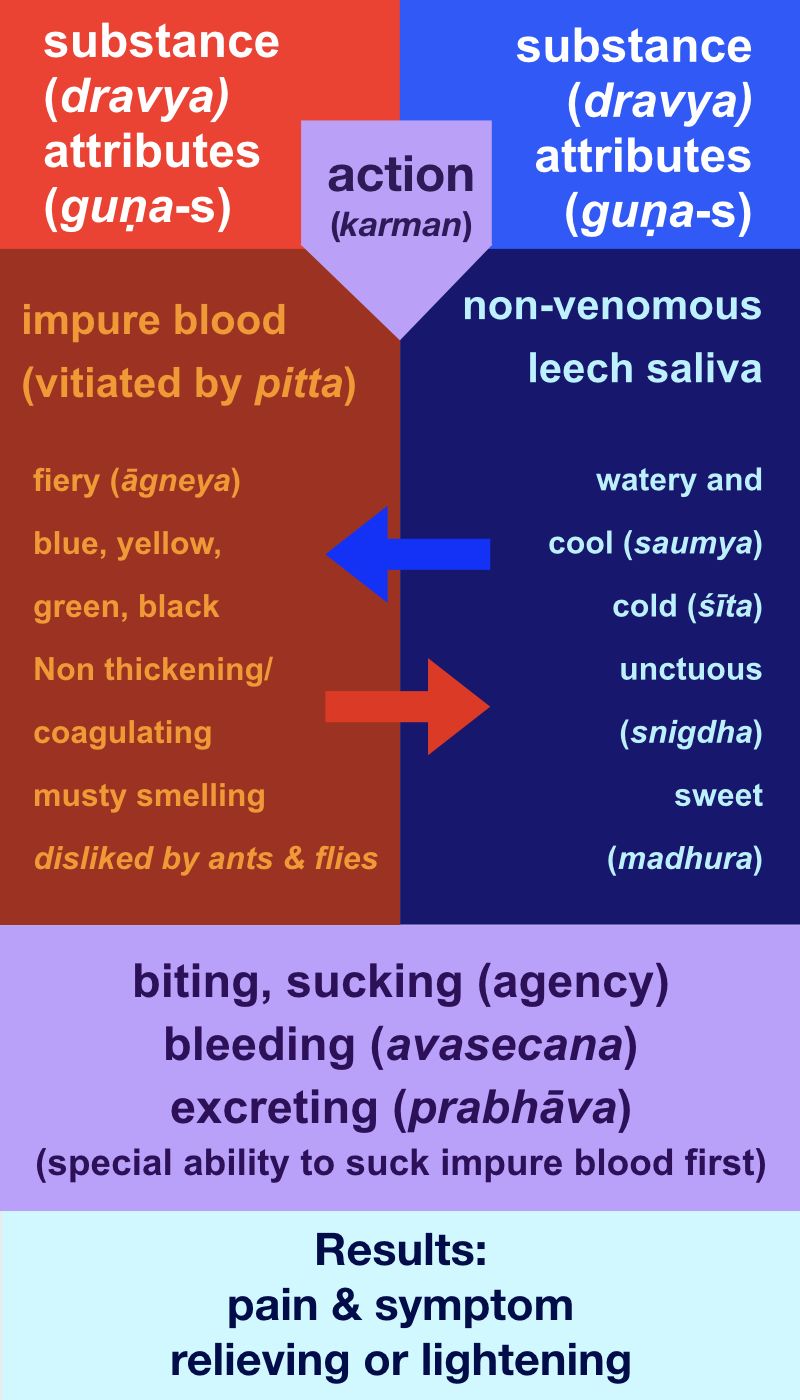

According to the Suśrutasaṃhitā, a Sanskrit Āyurvedic treatise specialising in surgery written approximately 2,000 years ago, bloodletting (raktamokṣa) is an essential treatment for removing excess or spoiled blood. Bloodletting is the action (karman) of drawing a substance (dravya)—blood—from the human body. In this process, a transformation of attributes (guṇa-s) takes place, effecting healing.{{1}}{{{The relationship between substance (dravya), attribute (gụna) and action (karman) is essential to understanding the mechanism of treatments from the perspective of classical Āyurvedic treatises. Substance (dravya) is the substrate in which both attribute (guṇa) and action (karman) reside. Attribute (gụna) and substance (dravya) exist in a relationship of inseparable concomitance (samavāya), as matter and attribute invariably coexist (Carakasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna (Sū) 1.49–53). Here, I use the terms as both an organisational framework and an analytical tool for studying the mechanisms of leech therapy. The complete set of six fundamental factors discussed in the Carakasaṃhitā Sū, Chapter 1, are sāmānya, viṣeśa, guṇa, dravya, karman and samavāya (1.28). The Carakasaṃhitā (CS) and Suśrutasaṃhitā (SS) are both comprised of sections further subdivided into chapters; each of these sections is called a ‘sthāna’. Both treatises begin with a general section called the ‘Sūtrasthāna’, henceforth referred to as Sū.}}}

The Suśrutasaṃhitā describes two standard techniques for bloodletting, pricking and venesection, and three gentle means: horn (śṛṅga), bottle-gourd (alābu) and leech (jalaukas).{{2}}{{{Suśrutasaṃhitā Sū, Chapters 12 and 13 describe the five methods of bloodletting.}}}

Each of the three gentle means of bloodletting has attributes (guṇa-s) suited to treating conditions predominant in a particular Āyurvedic doṣa—fault or humour. The doṣa-s—vāta, pitta and kapha—are often translated as wind, bile and phlegm.

Among the methods of bloodletting, one stands apart. It is not only the gentlest, but also the only one in which two substances—human blood and leech saliva—come into transformative contact with one another via the sucking action of a living being: leech therapy (jalaukāvacāraṇa).{{3}}{{{The early first millennium medical treatise, the Suśrutasaṃhitā, contains the first detailed description of leech therapy attested in the Āyurvedic corpus. The Suśrutasaṃhitā is the primary classical reference for this essay, along with Ḍalhaṇa’s twelfth-century Nibandhasaṃgraha commentary. All translations are by the author.}}}

Leeches are described as sweet, as inhabiting cold places and as born in water; therefore, they are optimal for treating the fiery nature of a pitta or bile-predominant condition.

In contemporary Āyurvedic practice in India, leech therapy is the most common of the three gentle means of bloodletting and it is used to treat a variety of conditions, including arthritis, swelling, skin disorders and ulcers.{{4}}{{{Photographs and videos were taken by the author with informed consent at a clinic in Southern Kerala during two years of field research. The clinic name has not been used to protect the privacy of patients and staff and in accordance with the UC Berkeley Institutional Review Board’s protocol. For an ethnography of this clinic, which specialises in a leech therapy protocol for venous ulcers, see Lisa Allette Brooks, ‘The Vascularity of Ayurvedic Leech Therapy: Sensory Translations and Emergent Agencies in Interspecies Medicine’, Medical Anthropology Quarterly, forthcoming; Lisa Allette Brooks, ‘Translating Touch in Āyurveda’ (PhD diss., University of California Berkeley, forthcoming).}}}

In the clinical practice of leech therapy, leech and human agencies co-constitutively emerge. To a great extent, leeches’ inclinations determine the exchange and transformation of fluids and attributes taking place in the patient’s body that constitute healing.

Two Sanskrit etymologies for ‘leeches’ are given in the Suśrutasaṃhitā: ‘“jalāyukāḥ” “those whose life is water” and “jalaukasaḥ” “those whose abode is water”’.{{5}}{{{Suśrutasaṃhitā Sū, 13.6.}}} Compared to the Latin sanguisuga, ‘bloodsucker’, which highlights leeches’ action of feeding on human blood, the Sanskrit names emphasise water as the lifeworld, habitat and very nature of leeches.

Most classical Āyurvedic treatises include a typology of six venomous (saviṣa) and six non-venomous (nirviṣa) leeches described as homologous with their respective environments: ‘Venomous leeches arise in the rotting of venomous fish, insects and frogs, (in their) urine and faeces, and in dirty water. Non-venomous leeches arise in the rotting of lotuses … and in clean water.’{{6}}{{{Suśrutasaṃhitā Sū, 13.14–15.}}} According to the treatises, leeches are understood to come into existence not through reproduction, but by ‘sprouting forth’ (udbhijja) from decaying matter.

As fluid bodies, non-venomous leeches are agents of transformation through the circulation and exchange of fluids. With their cooling and moist saliva, they remove and pacify fiery vitiated (duṣṭa) blood (rakta/śoṇita/asṛj).{{7}}{{{Ḍalhaṇa’s twelfth-century commentary to Suśrutasaṃhitā Sū, 14.7, reveals two scholarly interpretations of the relationship of blood with fiery (āgneya) and somic/cool and watery (saumya) qualities, and attests to multiple versions of the primary text circulating at the time of his writing. The verse explains that menstrual blood is fiery, as understood from the fact that the fetus, which is made from a combination of menstrual blood and somic semen (śukra), is both fiery and somic (ārtavaṃ śoṇitaṃ tv āgneyam agnīṣomīyatvād garbhasya | SS Sū, 14.7). In his commentary, Ḍalhaṇa understands blood (śoṇita) to also be fiery. However, at the end of his gloss on an alternate attestation of the verse, Ḍalhaṇa notes that some scholars ‘consider blood neither hot, nor cold’. Regardless, we learn later in the chapter that an increase in spoiled blood (duṣṭa śoṇita) causes heat (dāha) (tad duṣṭaṃ śoṇitaṃ anirhriyamāṇaṃ śophadāharāgapākavedanā janayet | SS Sū, 14.29). In clinical practice, blood and spoiled blood were both considered to be fiery. For further discussion of the position of blood in the SS and Ḍalhaṇa’s commentary see Brooks, ‘Translating Touch in Āyurveda’; Rahul Peter Das, The Origin of the Life of a Human Being: Conception and the Female According to Ancient Indian Medical and Sexological Literature, Indian Medical Tradition, vol. 6 (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2003), 129, 132; Dominik Wujastyk, ‘Agni and Soma: A Universal Classification’, Studia Asiatica 4 (2003): 356.}}}

Non-venomous leeches are understood to have the special capacity (prabhāva) to first suck vitiated blood from the human body. Thus, they are likened in classical treatises to the haṃsa (goose or swan), known in Sanskrit literature as having the unusual ability to drink only milk from a mixture of milk and water.{{8}}{{{The association of the special ability of leeches, in relation to blood, with haṃsas, in relation to milk, is first found in the seventh-century medical compendia of Vāgbhaṭa (Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya Sū, 26.42; Aṣṭaṇgasaṃgraha Sū, 35.4), and may be related to the ecologically homologous association of both with lotuses. It is notable that both leeches and haṃs-as are understood to live in lotus filled lakes and eat lotus root. See Charles R. Lanman, ‘The Milk-Drinking Haṅsas of Sanskrit Poetry’, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1898): 151–58.}}}

Action (karman): leech therapy (jalaukāvacāraṇa)

Leech saliva is a fluid.

When blood does not flow,

leeches suck, excrete, and transform.

To follow a leech to the clinic, we begin in a lotus pond.

Pond time is slow and seasonal.

According to the Suśrutasaṃhitā, a pond suitable for non-venomous leeches must be filled with clean water. This is indicated by it being populated by lotuses and other typologically similar flora and fauna.{{9}}{{{Suśrutasaṃhitā Sū, 13.14–15; Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya Sū, 26.35–38.}}}

A leech collector takes a leather bag or pricks his legs drawing blood, and then submerges the bait.{{10}}{{{See Sangeeth Kurian, ‘A Leech-Gatherer’s Tale’, Hindu, 10 October 2008; Brooks, ‘The Vascularity of Ayurvedic Leech Therapy’. According to the Suśrutasamhitā: ‘Their capture is by means of moist skin or one should take them by other means’ (SS Sū, 13.16). tāsāṃ grahaṇam ārdracarmaṇā anyair vā prayogair gṛhṇīyāt | Ḍalhaṇa explains the passage as follows: ‘He says, “their capture” etc. showing their means of capture. And their capture is in the fall season according to another treatise. “By other means”, indicates, or with parts such as shank etc. smeared with butter, ghee, milk, or a piece of flesh of the meat of a freshly killed animal.’ tāsāṃ grahaṇopāyaṃ darśayann āha tāsāṃ grahaṇam ity ādi | grahaṇam cāsāṃ śaratkāle tantrāntaravacanāt | anyair vā prayogair iti sadyohatajantumāṃsapeśīnavanītaghṛtakṣīr ādyabhyaktajaṅghādyavayavair vā |}}}

Following a successful harvest, an intermediary purchases the leeches and sells them to the clinic.{{11}}{{{In endnotes with citations from the Suśrutasaṃhitā, practice in the clinic is refracted through the idealised world of the treatise. Places in the English notes for this ethnographic vignette (translations and ethnographic analysis) where human–leech negotiations play a central role are in bold font. Both according to the treatise and in the clinic, physicians must properly care for leeches, discern their state of being, gather information from their behaviour, entice them to bite and, sometimes, force them to release. Physicians in the clinic practice leech therapy for venous ulcers in reference to the Suśrutasaṃhitā and the slightly later Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya, via a method learned from the clinic owner’s mentor, and woven in a complex and historically contingent relationship with biomedicine. The Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya is popular in Kerala and the section on leech therapy appears to be a distillation of the practice presented in the Suśrutasaṃhitā. Recipes for the medicines used in the leech therapy protocol are adapted from the later South Indian treatises, Sahasrayogam and Cikitsāmañjari. See Brooks, ‘The Vascularity of Ayurvedic Leech Therapy’; Brooks, ‘Translating Touch in Āyurveda’.}}}

After sorting out hard and hairy venomous leeches by touch and appearance, the cohort is stored in an oxygenated tank and fed periodically with packaged turtle food.

Leeches selected for a particular patient are housed in a small glass or plastic bottle on the shelves of a cabinet known as the ‘leech library’.

Once assigned to the leech library, leeches will live and, possibly, die in their jar when not feeding, purging or being washed.{{12}}{{{Leech ‘nourishment’ described in the Suśrutasaṃhitā exceeds leech care offered in contemporary clinics. The treatise explains: ‘Having poured mud and water from a pond or lake into a new large pot, one should place them [there]. For their food, one should offer duckweed, dried flesh, and aquatic bulbs, reduced to a powder. For their bed, aquatic grasses and leaves. After every three days, one should give them additional water and food, and after seven nights transfer them to another pot’ (SS Sū, 13.17). athaināṃ nave mahati ghaṭe sarastaḍāgodakapaṅkam āvāpya nidadhyāt bhakṣyārthe cāsām upaharec chaivalaṃ vallūram audakāṃś ca kandāṃś cūrṇīkṛtya śayyārthaṃ tūṇam audakāni ca patrāṇi tryahāt tryahāc cābhyo

’nyaj jalaṃ bhakṣyaṃ ca dadyāt saptarātrāt saptarātrāc ca ghaṭam anyaṃ saṃkrāmayet ||}}}

On this day, a patient has come seeking relief from his lower-leg ulcers (vraṇa-s).{{13}}{{{Chapters 21 and 22 of the Suśrutasaṃhitā Sū describe the conditions of vraṇa, with a general meaning of ‘wound’. Chapter 22 describes the different types of wounds and their exudates, including reference to a range of sensations, perceptible to the patient, at the site of the wound. These wounds can be located in a variety of tissues and patients often come into the clinic with ulcers that extend into the muscle. The full treatment regime includes oral and topical medications, compression bandaging, diet and lifestyle modifications and, sometimes, supplemental calcium and/or iron or antibiotic therapy.}}} In his job as a head-load worker, he spends long hours on his feet.{{14}}{{{Lower-leg venous ulcers more commonly afflict people in tropical climates who stand long hours or carry heavy loads, as well as those who have diabetes or postnatal varicosity.}}} The Āyurvedic physician goes to the leech library to retrieve his leeches.{{15}}{{{According to the convention in Kerala, a leech is used for only one patient.}}}

With a small piece of gauze between her gloved thumb and forefinger, the physician pries a leech from the edge of the jar.{{16}}{{{As described in this passage of the Suśrutasaṃhitā, the physician must be able to discern the state of the leech and spend time trying to engage it in the activity of biting. ‘Now, the patient—with a disease curable by bleeding with leeches— should sit or lay, and one should dry that location with clay and dried cow dung powders if there is no wound. Having taken [leeches], bodies smeared with water mixed with a paste of mustard and turmeric, recognising those relieved from fatigue, resting for a while in the middle of a vessel of water, one should seize the diseased area with them. Having covered [the leech] with soft, clean and moist cotton cloth, one should uncover the mouth. For those not taking hold, one should give a drop of milk or blood or one should make incisions. Only if, even then, it does not grab hold, then one should take another.’ (SS Sū, 13.19). atha jalaukovasekasādhyavyadhitam upaveśya saṃveśya vā virūkṣya cāsya tam avakāśaṃ mṛdgomayacūrṇair yady arujaḥ syāt | gṛhītāś ca tāḥ sarṣaparajanīkalkodakapradigdhagātrīḥ salilasarakamadhye muhūrtasthitā vigataklamā jñātvā tābhī rogaṃ grāhayet | ślakṣṇaśuklārdrapicuprotāvacchannāṃ kṛtvā mukham apāvṛṇuyāt agṛhṇantyai kṣīrabinduṃ śoṇitabinduṃ vā dadyāt śastrapadāni vā kurvīta yady evam api na gṛhṇīyāt tadā ’nyāṃ grāhayet ||}}}

The leech’s soft firm body is brown with pinkish orange black-dotted stripes along each side.

The physician brings the leech’s mouth to the centre of an ulcer on the patient’s left ankle. After a minute of squirming and adjusting, the leech takes hold. The leech’s head assumes the shape of a horse’s hoof, neck arching upwards, sucking blood.{{17}}{{{This visual cue is described in the Suśrutasaṃhitā. ‘And when it fixes, having made (its) face like a horse’s hoof and having bent upward the neck then one should know “it takes hold”, and having set the grasping leech, covered with a wet cloth, one should maintain it’ (SS Sū, 13.20). yadā ca niviśate ’śvakhuravadānanaṃ kṛtvonnamya ca skandhaṃ tadā jānīyād gṛhṇātīti gṛhṇantīṃ cārdravastrāvacchannāṃ kṛtvā dhārayet ||}}}

There is a strong, fast, pulsing

in the leech’s neck.{{18}}{{{In the clinic, physicians observe the frequency and amplitude of pulsation in the leech’s neck (indicating sucking speed) to infer the volume of blood flow and viscosity of blood at the site.}}}

The physician extracts another, and orients the leech towards the margin of a large irregular ulcer on the patient’s right calf.

The leech will not bite.

She places the leech in a metal tray and removes slough from the ulcer with gauze. Uncapping a sterile needle, the physician pricks the ulcer, drawing bright red drops of blood. Trying again, the physician positions the leech’s mouth over the ulcer.

After four minutes of negotiation, the leech is still not biting.

‘Naughty naughty’, she says. ‘It’s simply playing.’

Returning the leech to the jar she selects another.{{19}}{{{Although she has tried the techniques described in Suśrutasaṃhita Sū, 13.19, the leech does not bite, perhaps because the wound is dry (caused by vāta) or full of slough (caused by kapha). This particular refusal to bite is interpreted by the physician as confirming visible attributes (yellow slough) and suggesting additional attributes, such as extreme ‘toxicity’ of the blood. As the passage prescribes, only now may she engage another leech.}}} This one takes hold quickly and begins feeding. In the meantime, the first leech has released and speeds away, body expanding and contracting while moving towards the table’s edge. The physician catches the leech, places it in a tray, and continues her work. Eventually, four leeches are sucking and one is back in the jar. The physician covers their bodies with moist gauze and leaves the room.

After an hour, a leech releases from the patient’s leg, crawling away.{{20}}{{{Usually, the first leech would release on its own when finished. If the physicians determined that the length of the treatment was sufficient—between 60 and 90 minutes—they would use turmeric to cause the others to release.}}} The leech leaves a blood-streaked trail on the pink plastic table cover.

Bright red blood trickles from the open bite. Applying fragrant green medicated oil to a piece of cotton, the physician gently wipes up the patient’s blood. She presses a square of gauze saturated with the oil onto the wound.

Attribute (guṇa)

Fiery (āgneya ) / Cool and watery (saumya)

Hot (uṣṇa) / Cold (śīta)

Then, the physician picks up the leech. She strokes the leech from tail to head with her thumb. A thin stream of blood squirts from the leech’s mouth.{{21}}{{{According to the Suśrutasaṃhitā, and as explained to me in the clinic, the physician must be able to ascertain proper purging from the leech’s behaviour or the leech will die. ‘Now, the leech that has fallen off, having a body smeared with rice chaff [and] mouth anointed with oily salt, one should rub lengthwise very softly in the correct direction up to the mouth with the fingers and thumb of the right hand. One should purge [the leech] until there are signs of one “sufficiently purged”. The one sufficiently purged and placed into a water vessel, desirous of eating, should move. [The leech] sitting, who does not move, has vomited insufficiently. It should again be sufficiently purged. The incurable illness of (a leech) who has vomited insufficiently is called “indramada”’ (SS Sū, 13.22). atha patitāṃ taṇḍulakaṇḍanapradigdhagātīṃ tailalavaṇābhyaktamukhīṃ vāmahastāṅguṣṭhāṅgulībhyāṃ gṛhītapucchāṃ dakṣiṇahastāṅgulibhyāṃ śanaiḥ śanair anulomam anumārjayed āmukhāt vāmayet tāvad yavāt samyagvāntaliṅgānīti| samyagvāntā salilasarake nyastā bhoktukāmā satī caret | yā sīdatī na ceṣṭate sā durvāntā tāṃ punaḥ samyagvāmayet | durvāntāyā vyādhir asādhya indramado nāma bhavati | atha suvāntāṃ pūrvavat sannidadhyāt || (SS Sū, 13.22).}}}

After sprinkling turmeric onto the other leeches’ heads, they release onto the table.{{22}}{{{As seen in the clinic photos, turmeric is used because excessive application of salt can potentially kill the leech.}}} The physician lifts the leeches and places them into the metal surgical tray, applying more turmeric. Periodically, she takes the engorged body of a leech and dips the leech’s head in turmeric. The leech purges, arching and squirming in a swirl of orange and red.{{23}}{{{At this stage, physicians observe the purged blood, with ‘black’ blood indicating ‘toxic’ blood and bright red blood indicating health. Here, again, the leeches act as translators of matter for the physician.}}}

Eventually, the leeches are rinsed at the sink and placed back into the jar. Today, no leeches are washed down the drain into the clinic’s septic tank. Instead, they are returned to the leech library. The leeches rest in the cabinet for at least one week, more likely two, and, sometimes, indefinitely.{{24}}{{{At the clinic, when leeches die they are flushed down the toilet, returning to water.}}}

As noted above, leeches are understood to imbibe vitiated blood first, but when a patient experiences pain and itching, then a leech has started sucking healthy blood, constituting a clinical problem. This situation is addressed in the Suśrutasaṃhitā with a recognition of the agentive role played by leeches in the process of bloodletting: ‘It is said, through manifestations of pain and itching on the bite, one should understand that [the leech] takes pure (śuddha) [blood]. One should remove [the leech] taking pure blood. Now, if because of the smell of blood (śoṇitagandha), its mouth does not release, one should sprinkle it with sea-salt powder.’{{25}}{{{daṃśe todakaṇḍuprādurbhāvair jānīyāc chuddham iyam ādatta iti śuddham ādadānām apanayet atha śoṇitagandhena na muñcen mukham asyāḥ saindhavacūrṇeṇāvakiret || (SS Sū, 13.21).}}}

In his Nibandhasaṃgraha commentary, Ḍalhaṇa suggests two possible mechanisms for the itching that occurs when a leech is sucking pure blood. First, the pain (and itching) may be caused by wind (vāyu), generated from the destruction of the red component of blood (raktadhātu). Alternatively, the itching is caused by watery phlegm (kapha) destroying this fiery component of blood in contact with the leech’s saliva. Ḍalhaṇa makes a fascinating second point in his commentary on this passage, noting variant readings regarding the leech’s capacity to smell that suggests a debate over the leech’s sensory capacities.{{26}}{{{Ḍalhaṇa’s version of Suśruta states that if the leech does not release easily once it is sucking pure blood then it is ‘because of the smell of the blood’. However, Ḍalhaṇa comments that some reject this reading of the text and, instead of reading śoṇitagandhena, they read śoṇitagardhena ‘by means of desire for blood’, rejecting the possibility that leeches have a sense of smell. It is possible that the unidentified commentary mentioned reflects the Jain classification of moving beings according to the number of senses they have: one-sensed (touch/sparśa), two-sensed (touch and taste), three-sensed (touch, taste and smell), four-sensed (touch, taste, smell and sight) or five-sensed (touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing). But even this latter reading acknowledges that leeches play an agentive sensory role in the process of jalaukāvacāraṇa. See Brooks, ‘Translating Touch in Āyurveda’.}}}

A binary between fire and water, found in the earliest Indic literatures, is expressed in the Suśrutasaṃhitā through the opposing attributes.{{27}}{{{Dominik Wujastyk argues that ‘the Agni/Soma polarity expressed itself as a two-humour fire-water medical theory that is older than the classical three-humour doctrine in Āyurveda’. Dominik Wujastyk, ‘Agni and Soma: A Universal Classification’, Studia Asiatica 4 (2003): 366. This is supported by Natalie Köhle’s work arguing that bile (pitta) and phlegm (śleṣman/kapha) appear in the early strata of the Suśrutasaṃhitā as digestive fluids, predating tri-humoural (tridoṣa) theory. Natalie Köhle, ‘A Confluence of Humors: Āyurvedic Conceptions of Digestion and the History of Chinese ‘Phlegm’ (tan 痰)’, Journal of the American Oriental Society 136.3 (2016): 465–93.}}}

Analysed in terms of substance (dravya), attribute (guṇa) and action (karman), itching is either caused by the increase of wind via the action of sucking, or by the imbalanced interaction of the attributes of saumya (somic or watery leech saliva) with āgneya (fiery rakta). In both cases, the itching arises because of the loss of pure blood determined by leech inclinations.

As illustrated here, in the ideal case—that of a leech sucking impure pitta or bile-vitiated blood—the interaction of the watery leech with the fiery blood of the patient, entailing the removal of blood through sucking, results in relief for the patient. Not represented diagrammatically, but equally important, is the purging of the leeches to restore their watery and cool nature.

Both on the page and in the clinic, leeches, quite literally, matter. Their assent is a condition of possibility for treatment in a dynamic clinical intra-action.{{28}}{{{My ethnographic vignette and accompanying notes privilege the intra-actions of selves—multiply constituted emergent agencies—through touch and inter-sensorality. This study of jalaukāvacāraṇa is an exploration of forms of being in relation and, in Karen Barad’s terms, ‘intra-action’, assuming the imbrication of epistemology and ontology in the unfolding processes of knowing and becoming (Karen Barad, ‘Meeting the Universe Halfway: Realism and Social Constructivism without Contradiction’, in Feminism, Science, and the Philosophy of Science, ed. Lynn Hankinson Nelson and Jack Nelson (Dordrecht: Springer, 1997), 161–94; Karen Barad, ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’, Signs 28.3 (2003): 801–31).}}} Elsewhere, I explore the ‘vascularity’ of Āyurvedic leech therapy as an intervention in thinking about the formation of agencies at branching points in this interspecies medicine, mediated by tactile and inter-sensorial intra-actions.{{29}}{{{See Brooks, ‘The Vascularity of Ayurvedic Leech Therapy’.}}} In the process, human, leech and material agencies are enacted, determining the movement of matter and transformation of attributes taking place in Āyurvedic leech therapy. Leeches also act as translators of fluid matter, serving as sensory mediators for the physicians who not only negotiate with leeches to enrol them in the practice, but also observe them to gain vital information about the dynamic pathology of the patient’s condition.

IMAGE AND FILM CREDITS

Listed in the order in which images first appear in the essay.

Blood flow. The ToobStock, Drip in Water Stock Footage RED, 2011. The ToobStock © 2011. Video taken from YouTube. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Blood in wineglass. Image taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under a Pixabay License.

Wriggling/wrangling leech video. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Leech. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Leech application. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Leeches and foot. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Lotus pond. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Image taken in Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu near the border with Kerala. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Leech sorting. Madan Kumar, 2015. Madan Kumar © 2015. Reproduced with permission of the photographer.

Leech library. Madan Kumar, 2015. Madan Kumar © 2015. Reproduced with permission of the photographer.

Treatment room. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2015. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2015.

Biting. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Sucking. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Pricking. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Wriggling/wrangling leech film clip. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Red stripe. Image taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under a Pixabay License.

Purging. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Washing. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Leeches on lid. Lisa Allette Brooks, 2016. Lisa Allette Brooks © 2016.

Light on water. Image taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under a Pixabay License.

Fire and water fists. Image taken from Pixabay. Reproduced under a Pixabay License. Modified by author.

Pink lotuses. Image taken from Pxhere. Public domain (CC0 1.0). Modified by author.

Swan. SVG SIHL, n.d. Image taken from Wikipedia Commons. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0). Modified by author.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya with the Commentaries ‘Sarvāṅgasundarā’ of Aruṇdatta and ‘Āyurvedarasāyana’ of Hemādri. Edited by Aṇṇā Moreśwar Kuṇṭe and Kṛṣṇa Rāmchandra Śāstrī Navare. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan, 2012.

Aṣṭāṅgasaṁgraha with the Śaśilekhā Commendary by Indu. Prologue in Sankrit and English by Jyotir Mitra. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, 2012.

Carakasaṃhitā, Śrīcakrapāṇidattaviracityā Ayurvedadīpikāvyākhyayā Saṃvalitā. Edited by Vaidya Jadavaji Trikamji Ācārya. 5th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia, 2009. Reprint of the 1941 Bombay edition.

Suśrutasaṃhitā of Suśruta with the Nibandasaṅgraha Commentary of Śrī Ḍalhaṇāchārya and the Nyāychandrikā Pañjikā of Śrī Hayadāsāchārya on Nidanasthāna. Edited by Vaidya Kādavji Trikamji Āchārya and Nārāyaṇ Rām Āchārya. The Kashi Sanskrit Series 316. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan, 2015.

Secondary Sources

Barad, Karen. ‘Meeting the Universe Halfway: Realism and Social Constructivism without Contradiction’. In Feminism, Science, and the Philosophy of Science, edited by Lynn Hankinson Nelson and Jack Nelson, 161–194. Dordrecht: Springer, 1997. doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1742-2_9

Barad, Karen. ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’. Signs 28, no. 3 (2003): 801–831. doi.org/10.1086/345321

Brooks, Lisa Allette. ‘The Vascularity of Ayurvedic Leech Therapy: Sensory Translations and Emergent Agencies in Interspecies Medicine’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, forthcoming. doi.org/10.1111/maq.12595

Brooks, Lisa Allette. ‘Translating Touch in Āyurveda’. PhD diss., University of California Berkeley, forthcoming.

Das, Rahul Peter. The Origin of the Life of a Human Being: Conception and the Female According to Ancient Indian Medical and Sexological Literature. Indian Medical Tradition, vol. 6. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2003. doi.org/10.1007/s10783-006-3444-3

Köhle, Natalie. ‘A Confluence of Humors: Āyurvedic Conceptions of Digestion and the History of Chinese “Phlegm” (tan 痰)’. Journal of the American Oriental Society 136, no. 3 (2016): 465–93. doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0465

Kurian, Sangeeth. ‘A Leech-Gatherer’s Tale’. Hindu, 10 October 2008, n.p. Accessed 14 March 2018.

Lanman, Charles R. ‘The Milk-Drinking Haṅsas of Sanskrit Poetry’. Journal of the American Oriental Society (1898): 151–158. doi.org/10.2307/592478

Wujastyk, Dominik. ‘Agni and Soma: A Universal Classification’. Studia Asiatica 4 (2003): 347–369.

This essay should be referenced as: Lisa Allette Brooks, ‘Whose Life is Water, Whose Food is Blood: Fluid Bodies in Āyurvedic Leech Therapy’. In Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body, edited by Natalie Köhle and Shigehisa Kuriyama. Asian Studies Monograph Series 14. Canberra, ANU Press, 2020. doi.org/10.22459/FM.2020

MORE FLUID TALES

Introduction

1. Manipulating Flow

Whose Life is Water,

Whose Food is Blood

Lisa Allette Brooks