From the outset, Océanie was internally racialized, with skin colour and physical organization the key differentiae in the elaboration of region-wide racial taxonomies. Mentelle and Malte-Brun located the 'very beautiful', 'copper-coloured', 'Polynesian race' in what are now Polynesia and Micronesia and assigned it 'common origin' with 'the Malays of Asia'. They sharply differentiated 'the Polynesians' from the 'black race, that we can call Oceanic Negroes', which inhabited New Guinea, Van Diemen's Land, and what is now Island Melanesia, and from a probable 'distinct third race' in New Holland which they ranked 'only a single degree above the brute' and likened to 'the apes'. Malte-Brun reasoned that the 'tanned' and the 'black' races must issue from 'two stocks as dissimilar in physiognomy as they are in language, namely, the Malays or yellow Oceanians, and the Oceanic Negroes'.[20]

In 1825, the French soldier and biologist Jean-Baptiste-Geneviève-Marcellin Bory de Saint-Vincent (1778-1846) took the radical step of dividing the human genus into fifteen separate espèces, 'species'. He called his seventh espèce 'Neptunian' and divided it between three races: 'Malay'; 'Oceanic' (the present-day Polynesians); and Papou, 'Papuan',[21] a 'hybrid' product of the alliance of Neptunians and 'Negroes of Oceanica'. The Papous were 'the most truly savage of all Men' along with Bory's eighth espèce, named 'Australasian' and mostly comprising mainland Aborigines. Australasians were 'the most brutish of Men', 'totally foreign to the social state', 'misshapen', and with 'the most deplorable facial resemblance' to mandrills. Bory's penultimate espèce reconfigured the Negroes of Oceanica as Mélaniens, a term derived from Greek melas, 'black', referring explicitly to skin colour. This species included the inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land ('timid, stupid, idle'), most of what is now Melanesia ('warlike and anthropophagous to the highest degree'), and remote areas of the larger islands of the Malay Archipelago ('hideous Men').[22]

Bory drew effusively for this part of his taxonomy on two key voyage texts: Lesson's contributions to the Zoologie of the Coquille expedition; and the Zoologie of the Uranie voyage (1817‑20) produced by the naval surgeon-naturalists Jean-René Constant Quoy (1790-1869) and Joseph-Paul Gaimard (1793-1858) — Bory used 'Oceanic' in Lesson's restricted sense and owed his concept of hybridized Papous to Quoy and Gaimard.[23] Lesson (1829), a more ambitious classifier than most of his naval colleagues, divided 'the various Oceanians' (here using the term in its broad sense) into a tripartite racial hierarchy on the basis of physical organization, customs, presumed origins, and gross corporeal affinities. His '1st race', 'Hindu-Caucasic', derived from the Indian subcontinent and was divided between a 'Malay branch' and an 'Oceanian' one (present-day Polynesians) which he thought physically 'superior' to other South Sea Islanders. His '2nd race', 'Mongolic', was located in what is now Micronesia. His '3rd race', 'Black', was split into two branches: the 'Caffro-Madagascan' comprised a Papou variety inhabiting the New Guinea coast, nearby islands, and present-day Island Melanesia and a 'Tasmanian' variety in Van Diemen's Land; while the Alfourous occupied New Holland ('Australians') and the interior of New Guinea and some islands of the Malay Archipelago ('Endamênes').[24] Neither Papou nor Alfourou was a new term. In the early sixteenth century, Papua was a local toponym for islands to the west of New Guinea which Portuguese and Spanish travellers extended to the 'black' inhabitants of those islands and the New Guinea mainland. From the late eighteenth century, it was often generalized to 'black' Oceanian people as a whole. So-called Alfourous (Alfours, Alfoërs, Haraforas, etc.) were a recurrent, if elusive presence in Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French, and British colonial imaginaries from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries.[25]

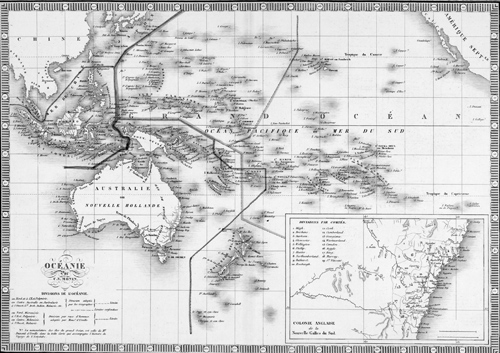

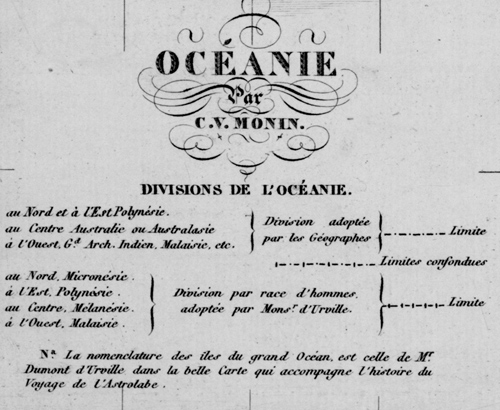

Dumont d'Urville's (1832) ethnological classification is more streamlined than these convoluted schemas, though no less racialized. He divided the inhabitants of Oceania into 'two distinct races' on the basis of skin colour, physical appearance, language, political institutions, religion, and reception of Europeans. Dumont d'Urville reworked Bory's term Mélanien into Mélanésien, 'Melanesian', as his general name for the 'black Oceanian race' which he found 'disagreeable' and 'generally very inferior' to the 'copper-coloured race' of 'Polynesians' and 'Micronesians' and to the 'Malays'. The 'Australians' and the 'Tasmanians' were at the base of this racial hierarchy as 'the primitive and natural state of the Melanesian race'.[26] The racial implications of Dumont d'Urville's cartography were taken for granted in 1834 by Charles Monin (18?-1880) whose map of 'Océanie' overlaid the 'division adopted by the geographers' into Polynesia, Australasia, and the Indian Archipelago with Dumont d'Urville's 'division by race of men' (Figures 3, 3a). By 1830, few Euro-Americans would have disputed Dumont d'Urville's presumption of the material reality of discrete, physically defined, differentially endowed human races, though the origins, import, and future implications of racial distinctions were bitterly contested. His racial nomenclature for Oceania was quickly adopted in France but was viewed ambivalently by many anglophone writers. The American Hale (1846:3-116) fully embraced it and lauded the 'propriety' of correlating geographical 'departments' with 'the character of their inhabitants'. In mid-century, the Anglican Bishop of New Zealand, George Augustus Selwyn (1809-1878), appropriated Dumont d'Urville's neologism to name the Melanesian Mission, his peripatetic evangelistic enterprise in the southwest Pacific. Selwyn sometimes also used the term as a linguistic and racial label but, unlike the Frenchman, did so non-pejoratively, maintaining 'that civilization is a mere name, and that religion is the only real ground of difference between the various races of mankind'.[27] Robert Henry Codrington (1830-1922), a subsequent head of the Melanesian Mission, used Melanesian and Polynesian as anthropological labels but limited Melanesian to the island groups east and southeast of New Guinea. He too refused the idea of racial hierarchy. Prichard, in contrast, rejected Dumont d'Urville's wording — Melanesian lacked 'etymological accuracy' and should be replaced by 'Kelænonesian' — but rehearsed his invidious racial discrimination: 'the black races in Oceanica' were 'very different from' and 'very inferior to the Malayo-Polynesians'.[28]

Engraving. MAP T 913/2. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Engraving. MAP T 913/2. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

For much of the nineteenth century, English racial terminologies for Oceanian people were more varied and ambiguous than French, due in part to differing emphases in the respective fields of inquiry. In Britain, the science of man had strongly philanthropic roots and drew much empirical sustenance from missionary ethnography.[31] In France, the science of race was a highly deductive outgrowth of biology and physical anthropology, fed by the work of travelling naturalists.[32] Yet, notwithstanding principled humanitarian antipathy to the dehumanizing tendencies of the science of race, English writings on man were steadily infiltrated by racial logic and language. The authors of works on Oceania, including missionaries, routinely differentiated the 'black' 'Polynesian negro' from the 'brown' or 'copper-coloured' 'proper Polynesian', or the 'Papuan' race from the 'Malayo-Polynesian' race, before normalizing varieties of Dumont d'Urville's binary system late in the century.[33]

[20] Malte-Brun 1803:548; 1813:228, 244; Mentelle and Malte-Brun 1804:474, 577, 612, 620, original emphasis.

[21] Since the French term Papou or Papoua does not always translate exactly into English 'Papuan', I retain the French forms as used and indicate their particular import.

[22] Bory de Saint-Vincent 1827, I:82, 94‑7, 273-318, 297, 306, 318-28; II:104-13.

[23] Bory de Saint-Vincent 1827, I:84, 99-101, 299, 304-6, 308-18; II, 108; Quoy and Gaimard 1824; Lesson and Garnot 1826-30.

[24] Lesson 1829:157, 168, 202-5.

[25] Ballard 2006; Gelpke 1993:326-30; see Chapters Two (Douglas) and Three (Ballard), this volume.

[26] Dumont d'Urville 1832:6, 11, 14-15.

[27] Hilliard 1978:12-13, 23; Selwyn to his father, 15 Sep. 1849, in Selwyn 1842‑67:216-19, 225-7, 230.

[28] Codrington 1881:261; 1891; Prichard 1836‑47, V:4, 212-13, 282, 283.

[29] 'Oceania: divisions of Oceania' (Monin 1834).

[30] Monin 1834.

[31] Gardner 2006:105-27; Herbert 1991:155-203; Sivasundaram 2005; Stocking 1987:8-109; see Chapters Six (Gardner) and Seven (Weir), this volume.

[32] Moussa 2003; Staum 2003; see Chapters Two (Douglas) and Five (Anderson), this volume.

[33] E.g., Brown 1887:312, 320; 1910; Ellis 1831, I:78-9; Erskine 1853:2, 4, 13, 241; Inglis 1887:5; Robertson 1902:1; Williams 1837:503-4, 512. See also Gardner 2006:114-20; Kidd 2006:121-67.