We apply 'Oceania' historically to the vast insular zone stretching from the Hawaiian Islands in the north, to Indonesia in the west, coastal Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand in the south, and Easter Island in the east. This extended sense reinstates the cartographic vision of the French geographers and naturalists who invented the term and transcends its restriction to the Pacific Islands in much later anglophone usage, including recent strategic appropriations by indigenous intellectuals concerned to negotiate postcolonial identities.[10] As originally conceived, Oceania embraced the Asian/Indian/Malay Archipelago or East Indies (the island of Borneo, modern Indonesia, Timor-Leste, Singapore, and the Philippines), New Guinea (modern Papua New Guinea and the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua), New Holland (mainland Australia), Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), New Zealand (Aotearoa), and the island groups of the Pacific Ocean (soon to be distributed between Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia). The two centuries spanned by this volume comprise only a small, recent, mostly colonial fraction of the more or less immense length of human occupation of these places, estimated by archaeologists to range from as much as 65,000 years in Australia (and presumably earlier in Island Southeast Asia) to fewer than 800 years in Aotearoa.[11]

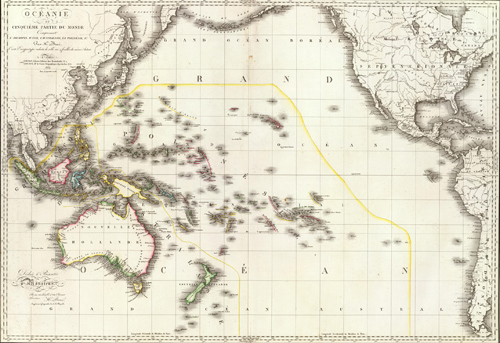

In 1804, Edme Mentelle (1730-1815) and Conrad Malte-Brun (1775-1826) coined the name Océanique, 'Oceanica', as a more precise label for 'this fifth part of the world usually grouped under the generic name of Terres australes', or 'southern lands'. The French term had pluralized Terra Australis incognita, the fifth continent of cartographic imagination since the early sixteenth century.[12] In 1756, the littérateur Charles de Brosses (1709-1777) proposed a geographic tripartition of this 'unknown southern world'. Polynésie (from Greek polloi, 'many') denoted 'everything in the vast Pacific Ocean' and encompassed what are now Polynesia, Micronesia, and much of Island Melanesia. Australasie (from Latin australis, 'southern') was located 'in the Indian Ocean to the south of Asia' and lumped hypothetical vast unknown lands together with actual places seen by voyagers in New Guinea, New Holland, Van Diemen's Land, New Zealand, and Espiritu Santo (in modern Vanuatu). Magellanique — a synonym for Terra Australis in earlier cartography — was for Brosses a purely speculative land mass stretching to the south of South America.[13] Mentelle and Malte-Brun retained only Polynésie from Brosses's nomenclature but, whereas Brosses had made it an umbrella label for the 'multiplicity of islands' in the Pacific Ocean generally, they contracted it to what would become Polynesia and Micronesia and substituted Océanique for the regional whole. In 1815, Adrien-Hubert Brué (1786-1832) in turn amended Océanique to Océanie, 'Oceania' (Figure 1).[14] In 1832, the navigator-naturalist Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d'Urville (1790-1842) lent his considerable empirical authority to the name and broad geographic span of Océanie and in the process initiated the distribution of the Pacific Islands and their inhabitants between Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia (Figure 2). Dumont d'Urville's terminology was formally adopted by the French Navy and popularized by his rival classifier Grégoire Louis Domeny de Rienzi (1789-1843), author of the highly derivative but widely-read Océanie ou cinquième partie du monde, 'Oceania or Fifth Part of the World' (1836-8).[15]

Engraving. David Rumsey Map Collection. Fulton, MD: Cartography Associates.

'Oceanica' evidently entered English in the 1820s via a translation of Malte-Brun's Universal Geography (1825) and was borrowed in the 1840s by two distinguished anglophone writers. The American philologist and ethnologist Horatio Hale (1817-1896), a member of the United States Exploring Expedition to the Pacific in 1838‑42, made it his general label for all the land 'between the coasts of Asia and America', including New Holland and the 'East Indian Archipelago' (1846:3). And the British ethnologist James Cowles Prichard (1786-1848) found it the logical name for 'all the insulated lands that have been discovered in the Austral Seas', as far as and including Madagascar. A decade earlier, Prichard had occasionally used the phrases 'Oceanic race', 'nation', or 'tribes' but at that time limited 'Oceania' to 'the remote groupes' of Pacific Islands — a usage derived from the idiosyncratic racial taxonomy published by the French naval pharmacist and naturalist René-Primevère Lesson (1794-1849) following his voyage round the world on the Coquille in 1822-25. Lesson had restricted 'Océanie properly speaking' to what is now called Polynesia and applied what might have been an early Portuguese usage of Polynésie to denominate the 'Asian archipelagoes', including New Guinea.[17] By contrast, British Evangelical missionaries who proselytized in the Pacific Islands from 1797 resisted the new French geographical labels until late in the nineteenth century but retained Brosses's ocean-wide span for Polynesia, only splitting 'Western' from 'Eastern' Polynesia in the late 1830s in anticipation of their imminent encounter with a 'decidedly distinct', 'negro race' in the islands west of Fiji.[18]

Engraving. Photograph B. Douglas.

[10] For the limited geographic span of Oceania in English usages, see Great Britain Foreign Office 1920; and Oxford English Dictionary 2008 which defines the word thus: 'Oceania' — '(A collective name for) the islands and island-groups of the Pacific Ocean and its adjacent seas, including Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia, and sometimes also Australasia and the Malay archipelago' (my emphasis). The most notable indigenous reclaimant of this restricted sense of Oceania is Epeli Hau'ofa (1993:8) for whom the term signified 'a sea of islands with their inhabitants' (see also Hau'ofa 1998; Waddell, Naidu, and Hau'ofa 1993; Jolly 2001, 2007). Hau'ofa (1998:403-4) explicitly excluded the Philippines and Indonesia from Oceania because they 'are adjacent to the Asian mainland' and because they 'do not have oceanic cultures'.

[11] Higham, Anderson, and Jacomb 1999:426; Spriggs, O'Connor, and Veth 2006:9-10.

[12] Eisler 1995:12-54; Mentelle and Malte-Brun 1804:357-63. With 'America' designated the quarta pars, 'fourth part', of the globe and its fourth 'continent' (O'Gorman 1961:117-33, 167-8), any imagined southern land must henceforth logically have been the fifth part or fifth continent. The designation 'fifth part of the world' appears on the title page of the first Latin translation (1612) of a memorial to the King of Spain by Pedro Fernández de Quirós (1563?-1615) who in 1595 and 1606 had crossed the Mar del Sur, 'South Sea', from Peru on two voyages of exploration, colonization, and evangelism. However, the phrase 'fifth part' is not used in Quirós's original Spanish text of 1610 which refers to the 'hidden' southern part as comprising 'a quarter of all the globe' (Sanz 1973:37-8, 83).

[13] [Brosses] 1756, I:77-80. See, e.g., the map by Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) in which 'Terra Australis, or Magellanica, not yet revealed' encompasses much of the southern portion of the globe (Ortelius 1592). The classical theory that a large land mass must exist in the southern hemisphere to counterbalance those in the north was enthusiastically revived by Renaissance cartographers (Wroth 1944:163-74). The French mathematician Oronce Fine (1494-1555) first used the term 'Terra Australis', annotated as 'recently discovered, but not yet fully known', in his world map of 1531. In 1569, the Flemish cartographer Gerard Mercator (1512-1594) famously promoted the idea of a vast 'southern continental region' (Eisler 1995:37‑9) and he added the label 'Terra Australis' to his world map of 1587 with the note: 'Some call this southern continent the Magellanic region after its discoverer'. Eight decades later, the Dutch cartographer Pieter Goos (c. 1616-1675) treated sceptically the 'cal[l] for a fifth part of the world Terra Australis or Magellanica' and left blank the far southern portion of his world map (1668:[7], map 1). Yet most cartographers and geographers, including Brosses and the Scottish hydrographer Alexander Dalrymple (1737-1808), clung to a hopeful belief in the necessary existence of an 'immense' southern continent as a 'counterweight' to the great northern land masses until definitively proven wrong by James Cook ([Brosses] 1856, I:13‑16; Dalrymple 1770-1, I:xxii-xxx).

[14] Brué 1816; Mentelle and Malte-Brun 1804:362-3, 463-4.

[15] Dumont d'Urville 1832; Serres et al. 1841:652. Dumont d'Urville commanded the expedition of the Astrolabe to the Pacific in 1826-29 and circumnavigated the globe twice — as first lieutenant under Louis-Isidore Duperrey (1786-1865) on the Coquille (1822‑25) and in command of the Astrolabe and the Zélée (1837‑40). Domeny de Rienzi (1836‑8, I:1-3) claimed wide experience in western Oceania acquired during 'five voyages' as an independent traveller, particularly in the Malay Archipelago, but was reputedly an 'illusionist, creator of a fantasmagoric autobiography' (Bibliothèque nationale de France 2004).

[16] 'Oceania or fifth part of the world including the Asian Archipelago, Australasia, Polynesia, etc… 1814' (Brué 1816).

[17] Lesson and Garnot 1826-30, I:2, note 1; Lesson 1829:156-65, 216‑17, note 1; Malte-Brun 1810:495; 1813:229; Prichard 1837-46, I:xviii, xix, 251, 255, 298; V:1-3; 1843:326.

[18] Williams 1837:7-8, 503-4; see also Brown 1887:320; Inglis 1887:4; Murray 1863, 1874; Turner 1861.

[19] 'Map illustrating the memoir of Captain d'Urville on the islands of the Great Ocean' (Dumont d'Urville 1832: frontispiece).