I now shift from settler to tropical empire in order to reflect upon the contrast between New Zealand's domestic eulogizing of miscegenation and the tirades directed against half-castes in New Zealand's territory of Western Samoa. In 1914, New Zealand troops seized these islands from Germany and the League of Nations granted New Zealand the mandate after the War. New Zealanders were qualified for this administrative role, according to some spokesmen, because their record with Maori had demonstrated a gift for administering Polynesians (Cocker 1927:37). Yet some New Zealanders' attitudes to and treatment of half-castes in Western Samoa indicate a very different set of racial logics and imperatives.[43]

Though my ultimate destination is Western Samoa, I stop en route in Fiji, as was normal for passengers travelling by sea from Auckland to Apia. As sites of broadly similar tropical or managerial colonialism, Fiji and Western Samoa shared certain characteristics. The largest component of their populations was indigenous (though in Fiji, the Indian population, descended mostly from indentured labourers, was growing rapidly and would outnumber indigenous Fijians by the census of 1946). Europeans were a minority. Those Europeans born and raised in Fiji and Samoa included men and women of mixed race who were classed as Europeans, usually through a legally recognized European patriline.[44] The colonial administrations of Fiji and Western Samoa adhered similarly to the principle of the primacy of native interests. This was the proclaimed moral basis of the British administration in Fiji. The German administration of Western Samoa, which New Zealand inherited, had also subscribed to this ideal. After World War I, an ethic of modern, imperial responsibility, explicitly promoted by the League of Nations, endorsed it too. This principle needed, of course, a prior definition of the 'native' which tended to rely heavily on racial terminology. Between the wars, the principle of native primacy coexisted with a process whereby the categories race and class appear, in the anglophone managerial tradition of empire manifested in these colonies, to have been congealing into functional colonial castes.

This process was very marked in Fiji and contributed to the indignation some British officials felt towards European tourists disembarking from visiting ships during the twenties and thirties.[45] The relaxed behaviour of these white tourists and their friendliness with Fijians in the streets flouted the rules of social distance that expressed the division of the races. In Fiji's hierarchy of colour, Europeans were on top, with indigenous Fijians beneath them, and Indians at the bottom. The role of Europeans was to rule. The role of Fijians was simply to exist and reflect well on the administration by thriving and in some ways modernizing.[46] The role of Indians was to underpin the sugar industry through their labour. Race, for this colony, was an organizing principle, an identifier, and a value.[47] But as the discomfort caused by white tourists to some officials shows, this racial schema had difficulty accommodating people whose behaviour or colour did not fit the prescribed categories. While the political and economic aspirations of Indians posed the greatest challenge to Fiji's racial hierarchy, half-castes were threatening too. Those (of white, Chinese, Indian, or any other ancestry) reared as Fijians were controversial and offensive to the ideal of racial purity (Lukere 1997:211-34). But half-castes who were classed for legal purposes as Europeans were a problem felt even more keenly by the administration.

Much class differentiation could be found within this mixed-race category. The course of Fiji's colonial development had reduced opportunities for such people and most half-castes classed as Europeans were poor. White, expatriate managerial elites in the 1920s and 1930s increasingly rejected them.[48] The dominant ethnic Fijian in administrative circles, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna (1888-1958), described the problem thus: half-castes wanted greater political involvement but their educational level was little higher than that of Fijians. Socially rejected by Europeans and Fijians, 'they are easily carried away by appeals based on notions of equality'. Their numbers were rapidly increasing and they would soon swamp the vote of true whites: 'At no distant day the European electorate', said Sukuna (1983:176), 'will be white only in name, enlightened only in memory'. With its founding creed of native welfare, the administration had real difficulty with the political aspirations of those subjects who were racially excluded from the core relationship between indigene and ruler.

New Zealand interpreted the League of Nations mandate as placing Samoans in its sacred trust.[49] For the New Zealand administration, the category 'Samoan' did not include half-castes of Samoan ancestry who were classed as Europeans. In 1930, out of Western Samoa's total population of 40,722, persons of mixed descent classified as Europeans numbered roughly 2,320 (Keesing 1934:32).[50] As in Fiji, they were increasing rapidly and even greater class differentiation obtained among them. The majority were poor, landless, culturally closer to Samoans than Europeans, but proud of their European status. A minority were affluent. Unlike Fiji and also unlike American Samoa, Western Samoa had supported a comparatively large, nationally diverse European community numbering some 600 individuals in 1914.[51] Intermarriage was common between Samoan women and white men with longstanding business interests in the islands. Germany's relatively late imposition of effective colonial government in 1899 had prolonged the experience of a frontier ethic that was more accepting of interracial liaisons and no doubt helped to promote the exuberance of the mixed-race commercial community.[52] In the 1920s, Keesing (1934:461) observed that many of the older white men were dying off and nearly 200 Germans had left the territory. Consequently, children of mixed descent were inheriting family property and business. Many had been educated as Europeans but also participated in networks of Samoan kin. Indeed, there was sometimes economic advantage in their doing so. Such men, Keesing noted, lived 'in both mental worlds and know both moralities'. They occupied positions of considerable commercial and political influence.

New Zealand officials found both poor and well-off half-castes classed as 'Europeans' difficult. Regarding the former, one high official explained: 'It would not be fair to the Samoan in whose interests the islands are governed and the preservation of whose race is considered to be our duty, to give the half-caste the same status as the native with regard to the land … the half-caste must be left to sink to his level in the scale of humanity' (quoted in Keesing 1934:463). 'Europeans' who enjoyed traditional Samoan titles and use of Samoan land through their maternal kin were blocked from converting that land to freehold and were discouraged from exercising the political power associated with their titles. To represent Samoans in the Legislative Council, these 'Europeans' were required to abandon their European legal status and surrender associated rights, which none was keen to do (Meleisea 1987:171). Men of mixed race were also excluded from employment in government service.

Despite and perhaps partly because of New Zealand's zeal to run a model mandate primarily for the benefit of 'pure' Samoans, local Europeans, including prominent half-castes classed as Europeans, ganged up with other leading Samoans against the administration. The resulting mass Samoan movement of non-cooperation, the Mau, disabled New Zealand rule for several years in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The death of high chief Tupua Tamasese Leolofi after he was shot by New Zealand police at a peaceful demonstration of the Mau on 'Black Saturday', 28 December 1929, became a sombre symbol for Samoan nationalists of their people's resistance to colonial domination and their quest for political independence.

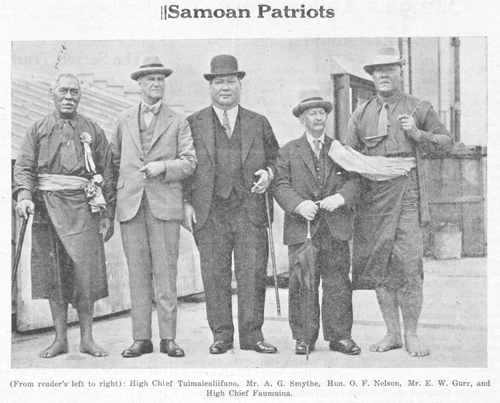

However, many contemporary European observers instead viewed the Mau in terms of the menace of the half-caste. The Mau was often described, especially in the early days, as a half-caste movement that lacked real Samoan support — for Samoans, so officials believed at the outset, did not like half-castes.[53] Demonstrations by the women's Mau were wont to be dismissed by officials as the actions of a rag-bag of half-caste women accompanied by well-known damsels of loose morals.[54] Many saw O.F. Nelson (1883-1944), a mixed-race businessman of girth, wealth, and intellect who also commanded high traditional status among Samoans, as the root cause of the trouble (see Figure 21).[55] When he and others were exiled to New Zealand, supporters of the Mau demanded to know why, if mixed-race men of Maori mothers were accepted as Maori leaders, the government rejected mixed-race men of Samoan mothers as leaders of Samoans (Anon. 1929). The official language vilifying Samoan half-castes — alleging their perfidy and cunning, their desire to oust European officials, their exploitation of naïve indigenous Samoans, the deplorable fact that so little British blood flowed in their veins (Nelson had none while German blood was said to vitiate most Samoan 'Europeans') — and the proposal, before the Mau came to a head, to solve the half-caste problem in the territory by exporting them all to New Zealand, demonstrate a striking difference between New Zealand's domestic and external racial lexicon and manners.[56]

Photograph. JAF Newspaper 079.9614NZS, Canberra: National Library of Australia.

[43] This chapter was first written without the benefit of Toeolesulusulu Salesa's sensitive meditation on half-castes in New Zealand and Western Samoa between the wars. Whereas Salesa (2000:99) at the outset stressed the ways in which the fortunes of half-castes in each context shaped each other, my starting-point has been the disjunctions between these histories.

[44] For a discussion of the legal complexities, however, see Shankman (2001) and Wareham (2002).

[45] See, e.g., Juxon Burton, Minute on Tourists and Fijians, 29 July 1936, in Colony of Fiji 1874-1941b: CF 50/12.

[46] In the context of this volume, Fiji is an interesting case because its native policy was founded on a conscious rejection of the nineteenth-century conviction that races like the Fijians were congenitally doomed (Lukere 1997:29-50).

[47] For a history well attuned to the racial dimensions of Fiji's twentieth century, see Lal 1992.

[48] Andrews 1937:114; Mann 1937:7-8; Scarr 1984:143, 156.

[49] Davidson 1967:76-113; Meleisea 1987:48‑51, 128-30.

[50] A further 959 'Europeans' were Chinese. Under the Samoa Act of 1921, 'A European is any person other than a Samoan' (quoted in McArthur 1967:118). The actual ethnic composition of the 'European' category was therefore difficult to analyze precisely (Keesing 1934:32).

[51] Keesing 1934:37‑40; Wareham 2002:177-178.

[52] Gilson 1970; Salesa 1997; Shankman 2001.

[53] See, e.g., comments by the Military Administrator of Western Samoa: Robert Logan, Report for Governor General on Administration of Samoa, 8 July 1919, in New Zealand Department of Island Territories 1919-40: IT1/10: 32-3.

[54] Stephen S. Allen, Telegram to Department of External Affairs, 3 April 1930, in New Zealand Department of Island Territories 1919-40: IT 1 Ex1/23/8 pt 18.

[55] Ian Campbell's reassessment of the Mau (1999) came close to the contemporary official interpretation of Nelson's involvement and also recognized New Zealand's good intentions under the terms of the mandate.

[56] See Richardson to Sir Frances Bell, 27 December 1926; Richardson to Minister of External Affairs, 13 December 1926; Richardson to Nosworthy, 26 July 1927; G.S. Richardson, Memo to Minister for External Affairs, 24 June 1927; and Bell to Richardson, 29 January 1925, in New Zealand Department of Island Territories 1919-40: IT 1 1/33/1 pt 1; IT 1 Ex1/23/8 pt 2; IT 1 Ex 1/33/1 pt 1. While anti-German feeling had been inflamed by the war and New Zealand officials were, for other reasons, mistrustful of German elements within Western Samoa and acutely sensitive to unfavourable comparisons with the earlier German regime, these anti-German sentiments cannot totally explain the administration's hostility towards half-castes in Samoa, as the parallels with Fiji, where the British did not have a comparable German element or legacy, suggest.

[57] N.Z. Samoa Guardian, 12 December 1929:1.