I suggest three general axes of variation to help explain the different evaluations of miscegenation that this chapter will address. The first is chronological. The conditions of frontier, as distinct from later colonialism often conduced to the acceptance of interracial liaisons and their offspring. This initially relaxed attitude to interracial sexual relations was partly a matter of sexual pragmatics since white women were usually scarce on the frontier. It could be partly strategic, since liaisons with local women could help white men gain useful knowledge and relationships. The children born of these unions, especially if their fathers or paternal associates cared for them, often became entrepreneurs in the frontier economies.

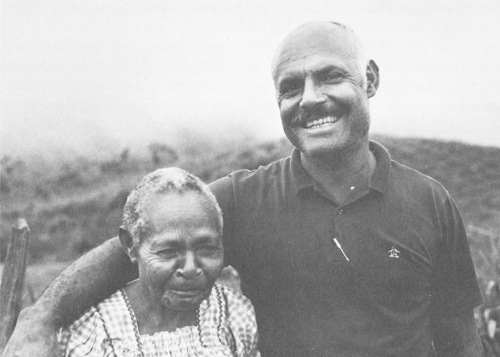

The photographs in Figures 19 and 20 — the first of a white father and the second of an indigenous mother and their son — illustrate certain significant features of frontier miscegenation. The son, Clem Leahy, was one of three mixed-race half-brothers by the same father, Michael Leahy, who led the first European expeditions into the New Guinea highlands during the 1930s and met Clem's mother, Yamka Amp Wenta, in the Mt Hagen area when she was sent to him by her husband. Though Michael Leahy did not acknowledge his children by local women, missionaries targeted his sons. All three were schooled by Christian missions and became successful businessmen.[9]

Photograph. nla.pic-vn4198892. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Photograph. © Robert Connolly and Penguin Group. Photograph B. Douglas.

More fundamentally, the parents in these photographs display the archetypically gendered ancestry of the European half-caste: father white, mother coloured.[12] There were of course cases — usually later — in which the mother was white and the father coloured but this occurrence was relatively rare and such sexual relations aroused hostility in European, especially male European, observers. Fernando Henriques (1974:78-92), in his classic survey of miscegenation beautifully entitled Children of Caliban, explored this antagonism. It was the subject of Amirah Inglis's (1975) examination of the White Women's Protection Ordinance in Papua. Claudia Knapman (1986:113-35) analyzed it in her study of white women in Fiji. Ann McGrath (1987:73) discussed it too in the 'cattle country' of Australia's Northern Territory. The most vivid cameos from my archival research relate to the nineteenth century. In Fiji in 1892, the white widow of a Colonial Sugar Refinery employee was living as wife with a Fijian chief. The administration denied him chiefly honours and the disgust of white officials is almost palpable on the page: 'The case is bad as it is'.[13] Still earlier, an elderly white woman who granted intercourse to Fijians for a small fee caused intense official indignation. She was deported.[14]

The photographs make a further chronological point. In many parts of Melanesia, such as the New Guinea highlands, empire was just beginning at or near the close of the imperial era. A map of Australia by the entomologist turned anthropologist Norman B. Tindale (1900-1993) traces further such examples.[15] During the decades following World War I, Australian frontiers were still advancing in the continent's north and centre and these areas were also the zone of first generation half-castes. But time cannot always be so neatly mapped. Different times may coexist. Elements of the culture of frontier can survive into later periods. As John Owens (1992:53) commented, 'Old New Zealand' — romanticized by some as the 'good old days' of the Pakeha-Maori, a term referring to Pakeha, 'Europeans', who 'went native' — continued in remoter areas. These social survivals combined with persisting values and memories derived from an earlier era to nourish, even to the present, an alternative tradition of race relations in New Zealand. A similar statement could be made for all the countries discussed here.

My second axis of variation is latitudinal. Throughout the colonial era and into the twentieth century, Europeans tried to explain the apparent toxicity, to them, of the tropics where they tended to sicken and die (Curtin 1990:136-8). One theory, not so very far from Alfred Crosby's (1986) classic explanation of the ecological determinants of European expansion, was that Europeans were constitutionally ill-suited to tropical climates. If the tropics were bad for white men, they were believed to be worse for white women. Aside from the usual scarcity of white women in such locations, these beliefs supported arguments in favour of interracial liaisons and also strengthened the case for hybrid progeny. For European enterprise in the tropics, half-castes could inherit from their fathers a loyalty, training, and taste for the activities of empire and from their mother — aside from contacts and local knowledge — acclimatization to their surroundings. These considerations probably influenced the vision splendid of one Wesleyan missionary in the 1840s, Walter Lawry (1739-1859), who looked forward to the day when a proud race of industrious Christians, descended from native mothers and white fathers, would populate the isles of the Pacific (1850:135).[16]

Beliefs in the toxicity of the tropics continued, however, into the interwar era. In Australia, though doctors like Raphael Cilento (1893-1985) — who liked to walk in the tropical sun without a hat — proclaimed that medical conquests, if combined with stringent racial segregation and sanitary discipline, now enabled white settlement of the nation's north, some expert and much popular opinion was less certain.[17] These doubts still supported certain arguments in favour of miscegenation. Thus Cecil Cook (1897-?), from 1927 Chief Medical Officer and Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Northern Territory, buttressed his case for marriage between mixed-race women and white men by saying that their children would derive, through their mothers, biological protection against skin cancer (a condition, incidentally, that plagued Cilento!).[18]

Associated with the idea of the toxicity of the tropics was the common contrast between temperate and tropical forms of colonization. Temperate regions were usually environmentally benign to Europeans and what Crosby (1986) calls their 'portmanteau biota' which included their associated plants and animals. Tropical colonies, however, were ecologically less hospitable to this European package. Broadly, different demographic histories and patterns of race relations correlate with these environmental differences. In the first, precipitous indigenous population decline, due to sickness, dispossession, and violence, was often accompanied by heavy European immigration, conflict over land, and troubled political relations between the indigenous minority and European majority in the subsequent evolution of a new, shared nation. In the second, whether or not the indigenous people were susceptible to introduced diseases, white populations rarely took deep root or abundantly flourished. Typically they amounted to no more than a minority who held managerial positions in administration, business, and the Christian missions. There was no comparable 'demographic takeover' (Crosby 1994:29-31).[19]

My third axis of variation is along a particular line of racial logic that sometimes favoured half-castes and sometimes not. The characterization of half-castes as infertile, prone to illness, lacking vitality, and combining the worst elements of both parental lines was commonplace. But derogatory assessments often coexisted with enthusiastic appraisals.[20] For example, in a lengthy official report into the reasons for the decrease of the indigenous Fijian population, published in 1896 and revived and feted between the wars, negative statements about half-castes can be read alongside arguments strongly in favour of racial mixing. The authors — all civil servants — were for instance keen to import Barbadians to interbreed with Fijians in order to produce a robust new racial hybrid (Stewart et al. 1896:184-7). One of these authors, Basil Thomson (1861‑1939), like innumerable English writers since Defoe, also gloried in the mongrel vigour of the British.[21] How can these apparently divergent assessments of miscegenation be reconciled?

Here the concept of racial distance is pivotal and can be illustrated by reference to animal breeding. The examples of the mule and the racehorse were often invoked. The mule was an age-old symbol of hybridization (and hence the term 'mulatto' for persons of mixed European and Negro ancestry).[22] It supposedly demonstrated the law that strains too far removed from one another mated unnaturally and produced defective offspring. The main defect of the mule was infertility. The racehorse, however, showed that by crossing distinctive but related strains and carefully mating their offspring in ensuing generations, a magnificent new breed could be produced (Pitt-Rivers 1927:6, 97). Of course, we could argue with such evaluations (what about, for instance, the virtues of a mule or the deficiencies of a racehorse?), but the influence of models drawn from animal breeding and horticulture was profound in both lay and specialist thinking about half-castes.[23]

For human miscegenation, the lesson usually drawn was therefore that crosses between races regarded as sufficiently close to one another were likely to prove beneficial while those between races considered too distant would not (e.g., Broca 1864:16-66). The historian Stephen Henry Roberts (1901-1971) clearly applied this principle in a chapter on race mixing in the Pacific (1927:352‑86). He acknowledged the old prejudice that all hybrids invariably combined the worst features of both parents. He acknowledged some experts who condemned even crossing closely related races. He also admitted the great diversity of opinion on all matters relating to race — including the repudiation of race as an entity. But Roberts did nevertheless confidently confirm this rule of racial distance. Thus, on the basis that Polynesians and Micronesians were deemed to be relatively close to Europeans and 'Asiatics', their mixture with European or Asian strains could be approved. Melanesians, however, were too distant from either Europeans or 'Asiatics' in Roberts' racial schema to be profitably combined with either. Roberts made no mention of Aborigines. Since a consensus of both expert and popular opinion had characterized the indigenous people of Australia as among the most primitive on earth,[24] the rule of racial distance did not favour the results of Aboriginal miscegenation with so-called higher races. But, as we shall see, racial distance was elastic.

[9] Connolly and Anderson 1987:242-3.

[10] Leahy [1933‑4].

[11] Connolly and Anderson 1987:278.

[12] Children of mixed but non-European ancestry raise questions that will scarcely be touched here (but see Lukere 1997:211-34; see also McGrath 2003; Shankman 2001; Wareham 2002). To say that the ancestry of the European half-caste is archetypically white on the father's side and coloured on the mother's can, of course, travesty the ancestry of individuals whose parents might both have had European forebears. Half-castes of later generations classified as 'Europeans', however, as a general rule inherited this status, along with a European surname, through a legally recognized patriline.

[13] Resolution 10 Concerning Jese Tagivaitana, Report of the Provincial Council of Tailevu, Nausori, 20 January 1892, in Colony of Fiji 1874-1941c: Resolutions 1892-94, Book No. 1, Tailevu.

[14] Superintendent of Police, Recommendation of the Removal of Mrs Murdock from the Colony, 17 January 1878, in Colony of Fiji 1874-1941a: Colonial Secretary's Office, CSO 78/93.

[15] Tindale 1941:82, figure 4.

[16] Lawry's vision of miscegenation can also be seen in terms of the Christian Evangelical tradition which contained within it creeds opposed to the racial compartmentalization of humanity. See Chapters Six (Gardner) and Seven (Weir), this volume.

[17] Cilento (1959:437) remarked that the Australasian Medical Congress in 1920 had, in opposition to traditionalists, affirmed the feasibility of the white colonization of the tropics. Aside from 'traditionalists' within medical circles, some prominent geographers remained doubtful and, as David Walker (1999:153) observed, 'the stigma of tropicality' persisted until the late 1930s. For a fuller discussion of perduring misgivings, see Anderson 2002:164-74.

[18] Cook, quoted in McGregor 1997:169; Yarwood 1991:54-5.

[19] During the interwar era, Cuba and Puerto Rico were virtually the only colonies within the tropics where people of predominantly European descent comprised the majority (Kiple 1984:7). In New Caledonia and Hawaii, the Pacific Island groups with the largest European populations at that time, whites were — and remain still — a minority (Connell 1987:97; Nordyke 1989:178-9). For these reasons, Cilento (1933:432) stressed Australia's uniqueness: 'we have a greater population, purely white, living in the tropics than any other country in the world can boast'.

[20] For a general discussion of pejorative characterizations of people of mixed race, see Stepan 1985:104-12. See Chapter One (Douglas), this volume, on the key status of racial mixing in scientific debates about the unity or plurality of human species from the mid-eighteenth century and on the racialism of arguments both in favour of and against human hybridity.

[21] Defoe quoted in Dover 1937:99; Thomson 1908:ix; see also Barkan 1992:23.

[22] Ritvo 1996:41; Stepan 1985:106; Young 1995:8.

[23] Paul 1995:110-11; Ritvo 1996:45; Stepan 1985:106, 108; Young 1995:11-12. The question of the infertility or otherwise of hybrids was pivotal in naturalists' debates on the concept of species at least from the mid-eighteenth century. The French anatomist and anthropologist Paul Broca (1824-1880) based his influential short monograph on human hybridity — the first systematic study of the subject, quickly translated into English (1864) — on a thorough study of hybridity in animals. See Chapter One (Douglas), this volume.

[24] See Chapters Two (Douglas), Four (Turnbull), and Five (Anderson), this volume.

![Figure 19: Anon., 'Michael Leahy in the Wahgi Valley, 1934'.Leahy [1933‑4].](../images/fig19.jpg)