This shifting emphasis and its accompanying discourse were exemplified in the debates within Australia on the League of Nations mandate over New Guinea. Many Christians accepted the ideals inherent in the League of Nations as a mechanism that would maintain peace and ensure the past war could never be repeated. This vision, most notably connected with the United States President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), aimed to 'vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power' through councils of collective security which would intervene to prevent quarrels escalating.[15] Wilson, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was profoundly motivated by Christian belief and ethics which underpinned his public life. He believed in a covenant between God and human beings within which human beings had the responsibility to strive to give the world structure and order (Mulder 1978:269-77). The Covenant of the League of Nations, with its provision for regular conferences, marked the culmination of that vision — but the failure of the United States to ratify the covenant or take part in conference deliberations undermined the whole system. Grant's (1920:xxx) demand that the 'Nordic' race 'discard altruism' and the 'vain phantom of internationalism', which he believed to be both unscientific and potentially dangerous, resonated with the views of more conservative American politicians. Subsequent judgement on the League of Nations has been harsh but the major powers systematically deprived it of any ability to be effective, mostly by absenting themselves. Yet in Australia and the Pacific Islands, the League of Nations Covenant did have a particular importance, perhaps validating the comment by Norman Davies (1996:950) that the League 'played a major role in the management of minor issues, and a negligible role in the management of major ones'. For under the terms of Article 22 of the Covenant, Australia gained a mandate over the former German New Guinea. While Wilsonian principles generally disapproved of colonialism and supported self-government for smaller states, it was recognized that some peoples were 'not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world'. In such cases their 'well-being and development … form[ed] a sacred trust of civilization', a duty which, in the case of New Guinea, devolved to Australia.[16]

But if Christians accepted the responsibility inherent in such a mandate, much popular and government opinion disagreed with them. In May 1921, the military government of the former German New Guinea was replaced by a civilian administration under the terms of the League of Nations mandate. Exactly what this mandate meant was the source of considerable tension within Australia. Prime Minister William Morris Hughes (1862-1952) saw control of New Guinea as a strategic matter, ensuring that 'the great rampart of islands stretching around the north-east of Australia' would, as he had demanded at Versailles, be 'held by us or by some Power in whom we have absolute confidence'. For Hughes, possession of New Guinea formed a sizeable part of the reparations due to Australia (Hudson 1980:27-30).[17] He rejected Wilsonian idealism and regarded the adoption of the Fourteen Points as 'an error — of judgement if you like'.[18] That was in public. His language in private was much less temperate and his hostility to Wilson unrelenting.[19] Others agreed with him in seeing New Guinea's importance in terms of what it might offer to Australia and not vice versa. The majority (Attlee Hunt and Walter H. Lucas) of the commissioners considering the form of administration for the mandated territory stated that 'the best and most humane principles' should govern the treatment only if this was 'consistent with the promotion of industrial enterprises tending to the benefit of the whole community', which included a large number of returned soldiers to be settled on the ex-German plantations. The 'evolution of the native' would consist in his moving 'from being a mere chattel of an employer to becoming an asset of the State'. The 'sacred trust of civilization' demanded by the mandate could be fulfilled by abolishing flogging.[20]

An alternative view was put by Hubert Murray (1861-1940), the chair but also the minority voice on the Commission. Murray had been Administrator of the Australian colony of Papua since 1906; his mode of government, though subject to both contemporary and modern criticism, was widely seen as taking into serious account the interests and concerns of the indigenous people and he regarded his administration as the obvious model for the newly mandated territory of New Guinea. The demands of Article 22 could not be satisfied if the development of the country was 'solely in the interests of the European settler' and if the 'natural duty of the native' was perceived to be 'to assist the European with his labour'.[21] Hence he advocated maintaining expropriated German plantations as a Government-owned business 'in the public interest'.[22] But Murray's vision did not prevail, and the majority report was accepted.

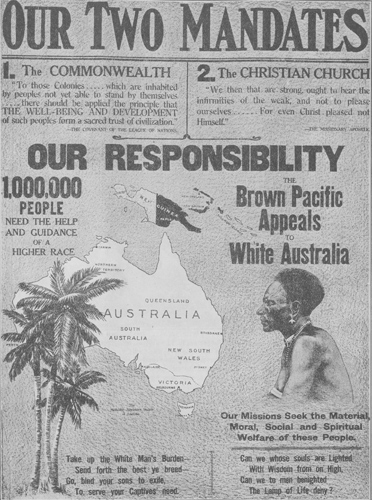

However, there were also strands of public opinion which supported Murray's view that the mandate was a 'sacred trust', expressed by people who, as far as they could, monitored the administration of the mandated territory. In May 1921, the month that the Australians assumed the mandate administration of New Guinea, the Methodist Missionary Review carried a remarkable image, apparently designed as a poster (Figure 18). The creator of the image is not named but it was probably Burton who was actively involved with the Missionary Review in 1921 and formally took over as editor in May 1922. Entitled 'Our Two Mandates', the poster juxtaposes state and Christian responsibilities. The left side carries two texts: the quotation from Article 22 of the League Charter concerning the 'sacred trust' and the first stanza of Kipling's poem 'The White Man's Burden' invoke the responsibilities of the Commonwealth. Balancing these on the right are the same citation from Paul's letter to the Romans earlier used by Paton and part of the missionary hymn by Bishop Heber of Calcutta, 'From Greenland's icy mountains', marking the responsibilities of the Australian churches. The dominant stress is on obligation, both secular and religious, with the implicit assumption that they were complementary. There is no distinction on the map between the mandated territory and Papua; the obligations are assumed to apply to both. Interestingly, the Melanesian figure is not, as in many appeals, that of a child or young woman but an adult male with traditional facial markings and body ornamentation. This could be read as conveying the depth of the need and the difficulty of the endeavour; certainly it is no mere sentimental appeal.

Yet alongside the language of duty and obligation and the reference to modern secular political realities, indeed, immediately below the words of the Covenant of the League of Nations, recourse is had to the ongoing language of social evolution: 'the Brown Pacific' needs the 'help and guidance of a higher race'. The word 'paternalism', with its inherent tensions, sums up this attitude — in both its more usual negative sense and in its appeal to fatherly care. This is made explicit in a lecture Burton gave in 1921 in which he compared humanity to a family with older, stronger members and also young, weak, 'less-equipped and undeveloped members'.

The true objective, if the family is to be perfect in all its relations, is to bring [the weak] into such a position where they might rightfully claim, without danger to themselves or others, the fullest privileges and the highest powers. 'Self-determination' is only latently theirs; and processes of education and training must be devised in order that they may come to full stature, and thus be able to discharge their responsibilities.

This is only possible when the stronger members are prepared to aid, to the utmost of their powers, the weaker and less advantaged members (1921:3).[23]

To perform this task was the reason, and the only reason, why Australia had been granted the mandate over New Guinea. In a striking conjunction of social evolutionism and humanist insight, Burton represented New Guineans as simultaneously 'inferior races' but with 'undeveloped' potential:

The Mandate is over undeveloped races. They have some measure of skill and capacity; but it is the skill of the stone age; the capacity of an untutored savage. We are asking them to perform a stupendous feat. We are proposing to them that in one gigantic leap they spring from the Stone Age, where we found them yesterday, to the Steel Age, where we are today. Consider what mental and social adjustment is required in such a movement! We have only to think back over a modern period in our own history, to provide ourselves with an illustration of the difficulties connected with such a change … What patient help and gracious chivalry then ought we not to extend to these inferior races who are asked to make adjustments far more profound that those we have attempted in our superior life (1921:5).

Poster. JAF 266.7MIS. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

The poster and the lecture, with their blend of evolutionism and the discourse of philanthropic/humanitarian obligation, epitomize the support for a vision of the League of Nations which existed both within the churches and outside. An active League of Nations Union in Melbourne aimed to educate citizens 'to equip themselves to discharge their responsibilities for a National undertaking' (Eggleston 1928: frontispiece). In seminars and 'round tables' about the mandate for New Guinea addressed by both church and secular figures, the desire was expressed to administer New Guinea with greater humanity than had been achieved with Aboriginal people. The League of Nations was seen as the model. Within church circles, enthusiasm was not confined to the Methodists and the claims made for the League of Nations could be effusive. The editor of the Anglican A.B.M. Review saw the Covenant's 'great principles of international brotherhood, co-operation and responsibility' as 'fundamentally Christian principles' and their adoption as 'due to Christian missionary work'.[25] W.N. Lawrence, an LMS missionary writing from Papua, believed that the formation of the League was 'a step towards the realization of the brotherhood of man and the Kingdom of God on the earth' (Chronicle, March 1919:41). The Australian Student Christian Movement backed the League of Nations as 'an institution whose principles were entirely in harmony with Christian ethics', welcomed the New Guinea Mandate, and urged members to use their influence 'to encourage the Federal Government in carrying out the high ideals of Article xxii of the Covenant'. International topics, including the White Australia Policy and policy towards the mandated territories, should be studied by student groups.[26]

In New Guinea, any interference by 'do-gooder anthropologists, missionaries, or presumed agents of the League of Nations' was resented by the new Administration and by European settlers (Nelson 1998). This did not stop continued surveillance by interested Christian and secular parties over the administration of the mandate. In 1928, Burton castigated the military ethos of the administration for 'hasty and dogmatic' decision-making, over-use of the indenture system which took men away from their villages, inadequate attention to preventative health measures, and an unsuitable (that is, too literary) education system; his essay (1928) was published in an academic political science study. Concern about the mandate and issues surrounding its administration meant that Australian Christian voices were now taking part in international debates. The issues of justice, social concern, and international relations which had been discussed within a limited milieu at the 1910 World Missionary Conference were now at the international centre stage and Australians, as citizens of a mandated power, had become major players.

[15] Woodrow Wilson, Speech to the United States Senate, 2 April 1917, cited by Knock (1992:121). In this speech Wilson promulgated his Fourteen Points which became the basis of the League of Nations Covenant.

[16] The text of the League of Nations Covenant is reprinted by Hudson (1980:208-14).

[17] For further discussion of Australian policy and official attitudes towards the mandated territory, see Nelson 1998.

[18] W.M. Hughes, Speech to the House of Representatives, 10 September 1919, Commonwealth of Australia 1919:12173, 12167. On Hughes's attitude to the Peace Conference, see also Offer 1989:371‑6.

[19] See, e.g., Hudson 1980:21-4.

[20] Report by Majority of Commissioners, 29, in Royal Commission on Late German New Guinea 1920.

[21] Report by Chairman, 55, in Royal Commission on Late German New Guinea 1920.

[22] Report by Chairman, 68-9, in Royal Commission on Late German New Guinea 1920.

[23] This lecture was delivered in the Melbourne Town Hall on 21 July 1921 under the auspices of the Victoria Branch of the League of Nations Union but was published by the Australian Student Christian Movement — another example of secular and religious linkage.

[24] Missionary Review, May 1821:7. The population figure of one million given in the image was the estimated population of both territories in 1921; Australians did not know of the existence of the large populations of the highlands region until the 1930s.

[25] A.B.M. Review, September 1920:104. The editor added that the Covenant had only twice been surpassed — by the Ten Commandments and the Sermon on the Mount — and twice equalled — by the Magna Carta and the Constitution of the United States of America.

[26] Report of the Commission to Consider the World Student Christian Federation International Findings, 14 May 1923, in Australian Student Christian Movement 1895-1997: Box 65, Item 3/5. The same report noted the view of the commission that the White Australia Policy could only be justified if 'Australia were to be used to the full by citizens of British stock and traditions'. If such a population did not completely occupy the continent, then other groups should be admitted; anything else was a 'dog-in-the-manger attitude'.