Cunningham's troupe was composed of nine Aborigines from the Palm Islands and Hinchinbrook Island off the coast of North Queensland. We do not know whether they went with him willingly and knowingly but their job was to play the role of wild savages as they toured North America in Barnum's Circus, appearing at fairs and dime museums.[6] They went on to England and Europe where they performed and were displayed at popular venues and were made available to anthropologists for examination and study. When the group arrived in Paris, only four of the nine were still alive — Toby and Jenny who were married, their child little Toby, and another man, Billy. The other five had succumbed to illness and died along the way. While in Paris, the four survivors stayed at the Jardin d'Acclimatation, gardens established to introduce and acclimatize exotic plants and animals. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, a number of such groups from exotic places was temporarily put on display there for the entertainment of the Parisian crowds but the Queensland group actually performed at the Folies-Bergère.[7]

The core of Topinard's 'Présentation de trois Australiens vivants' (1885) is a short report to the audience attending this 'live' demonstration on what he distinguished as the salient anthropological features of the three individuals. It should be noted that Jenny, Billy, and perhaps little Toby were actually present as Topinard spoke to his colleagues.[8] We do not, however, know how the room was set up or what the three subjects did while they were being discussed. Despite their reported linguistic skills, it is unlikely that they had picked up sufficient French during their short stay to enable them to follow the scientific discussion. They were probably addressed in English,[9] a second language for both the Aborigines and the French. Topinard (1885:683-6) began by describing how the presentation came about. The eminent anthropologist Hamy had learned of the troupe's stay in Paris from a colleague. He and Topinard visited them twice at the Jardin d'Acclimatation and also arranged for them to be examined at the laboratory of the Ecole d'Anthropologie. When Topinard and Hamy made their first visit, the fourth surviving member of the group, Jenny's husband Toby, was in hospital suffering from tuberculosis. He died the following day. Topinard said: 'I did all that I could, but to no avail, to have his body sent to the Broca laboratory, to be dissected'. During the anthropologists' second visit, Billy gave a display of his skills with the boomerang, an object of wonder to European scientists.[10]

After a brief account of the Aborigines' world tour, Topinard (1885:686‑7) noted that its members had been measured by other anthropologists. He then described the physical appearance of the man, the woman, and the child. Physical appearance — what could be observed from the outside and measured — was seen as crucial. Their skin colour was a 'deep yellowish chocolate'. The description and classification of their hair proved more problematic. Topinard dismissed previous reports of Aboriginal hair as straight and went into comparative detail about the diameter of the whorls of hair of the 'most favoured negroes' and 'the most inferior', the Bushmen. He maintained that the Australians' hair was closer to the 'woolly' hair of negroes than to the straight hair of the 'yellow races' and concluded that it was 'modified negro hair' formed of 'numerous but rather broad whorls'. He described their faces as follows:

With a full, rounded forehead, bulging and protuberant brow ridges, a deep root of the nose, very pronounced prognathism, particularly in the woman. The nose short vertically, wide at the base, triangular when it is seen face on, massive, with coarse and dilated wings; in brief what is called the Australoid nose (1885:688, original emphasis).

He generalized 'the Australoid nose' as 'Melanesian', by which he collectively meant 'Papuan, New Caledonian, Australian and Tasmanian', and deemed it 'so characteristic that by this feature alone an expert anthropologist can recognise a subject's Melanesian origin at first glance'. For Topinard (1885:688), the nasal index of the living subject — the ratio of maximum width to length of the nose — was of primary importance in classifying human races into the three basic divisions of white, yellow, and black. He found this feature at 'its maximum development' in the Australians.

Topinard (1885:689-90) used the figures obtained by his Belgian colleagues Houzé and Jacques for body measurements despite disagreeing with their figures and methods for the nasal index. He included a table comparing measurements of body height and the length of the head, trunk, leg, arm, hand, and foot for Billy, Jenny, and 'average European men'. He found that the Aboriginal man was shorter and had a smaller head, a longer trunk, a shorter leg, a longer arm, and a smaller hand (although the measurement in the table shows a larger hand) than 'the European', now singularized, but had much the same sized foot. The differences between the Aboriginal man and woman were not exactly 'average' but he cautioned against drawing firm conclusions from individual cases: 'What is typically true of a race is only to be found in its averages'. And yet Topinard's juxtaposition of individual physical measurements for Billy and Jenny with the European male average epitomized the metonymic use of individuals as specimens to stand for a whole race, a practice particularly marked in the raciological photography of this era.

The concluding paragraphs of Topinard's presentation (1885:690-1) focused on the question of Australian Aboriginal racial types, because, as he reminded his colleagues, he had already explored this subject at length in his article 'Sur les races indigènes de l'Australie' (1872), a review of mainly English-language literature about Aboriginal physical anthropology drafted as instructions to travellers to Australia concerning the collection of appropriate material. Topinard had argued there that the indigenous population was composed of two quite different racial types, one tall and handsome, the other small and ill-favoured, which could still be distinguished even though they had now interbred. Now, he provided his audience with a visual demonstration of this thesis in a photograph showing 'King Billy and his three wives' and a fifth individual, of a notably different 'type', who was 'relatively handsome' and 'very reminiscent of the true Ainu type'. He concluded: 'The three Australians here before us would represent the ugly type, the inferior race'.

Topinard's presentation was followed by discussion with contributions from about a dozen members, amongst whom the most prominent were Eugène Dally (1833-1887), Abel Hovelacque (1843-1896), a linguist and founder of the Revue de Linguistique, Hamy, Joseph Deniker (1852-1918), author of Les races et les peuples de la terre (1900), and the embryologist Mathias Duval (1844-1907). The record of the discussion is longer than the text of the presentation. It is immediately striking that all but one of the questions and comments relate not to the anthropometrical data gathered by Topinard and the Belgian anthropologists but to culture — that is, to ethnographic issues. The discussion ranged over the intelligence and dispositions of the Australians, their language, their numeracy, the systems of numeration of Aboriginal languages, scarification, cannibalism, and the Aboriginal sense of time. It concluded with a request from one member that 'the two Australians be made to speak aloud in their own language and also to sing'. It was recorded that 'The man performs with good grace and sings, accompanying himself by beating time with one stick against another' (Topinard 1885:697-8).

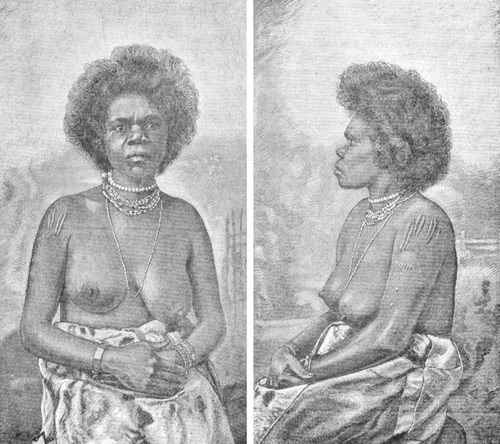

The published report includes two full-page engravings of Jenny after photographs taken by Prince Roland Bonaparte (1858-1924)[11]— a full-face portrait and a profile (Figure 17). In both, the top of Jenny's show dress is folded down to her waist revealing her breasts and her shoulders which are marked by cicatrices. She is wearing a number of bracelets and bead necklaces. She does not look directly at the lens of the camera but slightly off to the side and into the distance. The portraits are arresting because there is so little by way of illustration in the pages of the Bulletins — these are the only visual representations of a person in the seven hundred or so pages of this volume. They are also disturbing because we cannot now simply read her state of mind off the engravings and yet we know that this woman has experienced the deaths of most of her group during the tour and, depending on exactly when these photographs were taken, that her husband is either very ill in hospital or has just died.

Engraved photographs. Photograph: ANU Photography Services.

Curiosity about Indigenous Australians had been awakened in France in the late eighteenth century during the great era of European voyaging in Oceania. In 1793, idyllic encounters were recorded between Tasmanians and members of Joseph Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux's expedition. Nicolas Baudin's expedition of 1800-04 was the first to undertake 'anthropological' fieldwork and reporting and collected significant material about mainland and Tasmanian Aborigines.[13] But following the cessation of French voyaging on a grand scale after 1840, face-to-face interactions between French and Aboriginal people were rare. Henceforth, French scientists and the interested French public alike had to rely mainly on information about Aborigines written in English by British explorers, missionaries, settlers, and officials in the Australian colonies and on sensationalized popular accounts. Very few French anthropological reports about Aborigines, or indeed about non-European people generally, had been based on first-hand familiarity with living indigenous subjects.[14] Anthropologists either discussed the information they had obtained in their laboratories from measuring skulls and skeletons or borrowed ethnographic descriptions from accounts by observers on the spot. Their scientific texts were thus representations of representations. In this context, the visit to Paris of Cunningham's depleted troupe provided a rare opportunity to study Aboriginal people but even my brief synopsis suggests that it was an opportunity manqué because the scientists involved refused to engage with the Aborigines as fellow human beings but objectified them as racial specimens. By returning long after the heyday of raciology to this singular episode, it is possible to read off it some key elements in the intersections of French anthropology and Australian Aborigines, highlighting the ways in which Aborigines figured in the vigorous anthropological debates of the day.

[6] Poignant 2004:16-25, 59-104. There was a public outcry in Australia and questions were raised in parliament about the departure of the group (Poignant 1993:46; Houzé and Jacques 1884-5:97-8).

[7] See Topinard's editorial note in Mondière 1886:313; see also Poignant 2004:115-16, 164.

[8] Despite the title of the report, it is unclear whether little Toby was actually present. He is not mentioned in the presentation or the discussion and reference is made at the end to 'the two Australians'.

[9] Houzé and Jacques had used English in their meetings with the troupe in Belgium.

[10] E.g., Houzé and Jacques (1884-5:134-8) devoted some pages to a description of the dimensions and manipulation of the boomerang. Virchow (1884:417) was equally fascinated, marvelling at the complicated aerodynamics of its movement combined with the simplicity of the tool itself.

[11] Prince Roland Bonaparte was a great traveller, polymath, and generous sponsor of scientific research. He made early use of photography as a means of anthropological recording. Among his anthropological portraits, the photographs he took of the three surviving members of Cunningham's troupe have aroused considerable interest and were the starting point for Poignant's important work in bringing this episode to light (see Poignant 1993:37). These photographs are also discussed in Poignant 1992; 2004:4-7; Maxwell 2000; Anderson 2006.

[12] Topinard 1885:684‑5.

[13] See Anderson 2000 and 2001 for the embryonic ethnographic dimension of the two expeditions and Douglas 2003 for a discussion of the links between voyage ethnography and anthropological thought in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

[14] Exceptions include François Péron's (1983) account of the Aborigines of Maria Island, Van Diemen's Land, based on field observations made in 1802 during Baudin's expedition, and much later memoirs by the naval doctor Charles Cauvin (1882, 1883) who saw several Aborigines when his ship called at Melbourne and Sydney in 1879 but nonetheless concentrated on Australian skulls and skeletons held in French institutions.