For all of the differences between their individual accounts of Malays and Papuans, each of the three authors considered here subscribed to the central importance of a contrast drawn between a pair of putatively pure racial types. Yet all three also moved uneasily between the security of a simple pair of types and the chaos of encounters with a visual and behavioural variability that demanded either a more complex taxonomy or a more sophisticated account of the genesis of that variation.

Crawfurd's thoroughly contrived contrast of 1820 between Papuan and Malay could hardly stand the test of time. In his later works, he sought to incorporate the reports on Papuan physical appearance by the French Restoration voyagers and others.[67] By 1848, at least, he was writing of three 'groups' (1848:330-1): one of 'brown complexion, with lank hair', which encompassed various 'divisions', including the Malays of the western and eastern portions of the archipelago and the inhabitants of what Dumont d'Urville had already labelled 'Micronesia'; a second 'division' of 'sooty complexion, with woolly hair', 'usually called Papua', but which Crawfurd here designated the 'Oriental Negro' or 'Negrito'; and a new, third group 'of brown complexion, with frizzled hair', corresponding to the earlier French descriptions of 'mop-haired Papuans' residing along the coast of New Guinea and its adjacent islands.

Crawfurd's Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands (1856) contains three separate entries for 'Malay', 'Negro' (which included Papuans but referred only to non-African peoples), and 'Negro-Malayan Race'.[68] While he admitted that the category 'Negro' was the source of some confusion — 'there may be as many different races of negros as there are tongues, and in the present state of our knowledge, these are not countable' (1856:295) — Crawfurd claimed that his awkward 'Negro-Malayan Race' was not the result of mixture between the Malay and Negro races to its west and east, respectively. Rather, it was an intermediate race in its own right and one neatly bounded by a 'line of demarcation' on either side. Characterized by the conjunction of brown skin and frizzled hair, Crawfurd's Negro-Malay or 'quasi-negro' was to be found in the islands between New Guinea and Sulawesi — and he expressly identified Gilolo as one of the seats of this race (1848:331).

This theme resurfaced in the mid-1860s in Crawfurd's paper on the 'commixture of races' in which he sought to establish the long-term non-viability of interracial mixtures. Here (1865a:114), he drew a distinction between the 'pygmy Negro of the Malay Peninsula and Philippines' (effectively relocating his original 'puny Negro' off New Guinea's shores) and 'the stalwart Negro … of New Guinea, New Caledonia, and the Fijis'. He insisted, however, that among these 'native races there has been little commixture, and … none to the extent of forming a permanent cross-breed'. Crawfurd's fundamentally polygenist views could not tolerate a systematic 'admixture' of different races to account for this apparent hybridity (1856:296): 'it may be alleged to have arisen from an admixture, in the course of ages, of the Malay and Papuan races … but we do not observe any such admixture in progress,—and from the repugnance of the races it is not likely to have proceeded to any considerable extent'.[69]

While Crawfurd could write seemingly indiscriminately of 'our [human] race', 'the Negro race', and 'two races of negroes', all within the one paper (1848), and later of 'principal' and 'minor' races and even 'hybrid' races,[70] his articulation of the notion of interracial repugnance, which was strategically subscribed to by monogenists and polygenists alike, presumed some form of racial purity and required an increasing proliferation of distinct racial types.[71] Amongst his Negroes of the Orient, Crawfurd (1852:clxv) claimed to be able to detect at least twelve 'varieties' between the Andaman Islands and the Pacific. By the 1860s (1866:238), these different 'varieties' had become 'distinct races', seven of them alone among the Oriental Negroes — of whom it could 'be safely asserted that there is nothing common to them but a black skin, a certain crispness or woolliness of hair, thick lips, and flat features'. Each separate Negro race was considered aboriginal to the island in which it was now found and no common origin for them could possibly be detected. Crawfurd (1866:232) sought to impose a strong sense of order on this seeming chaos of taxonomic elaboration in the form of a hierarchy of relative 'superiority' or 'degree of civilisation', arrived at through a process of deduction that was arbitrary even by his own standards. Thus the African Negro was 'far above all the races of Oriental Negroes' while the Andamanese in turn were superior to Pacific Negroes because the former did not practice cannibalism. Only where Oriental Negroes came into contact with Malays, as at Dorey Bay, had they 'attained a certain measure of civilisation'.

Earl, who wrote of the 'utmost purity' of the two races of the Malay Archipelago, also struggled with the racial grey zone between the heartlands of the pure Malay and Papuan. He offered an explanation in which successive waves of 'Malayu-Polynesians', each differing from the other, had distributed themselves unevenly across the archipelago, thus accounting for pockets of the 'old Polynesian race' in places such as Ceram and Timor. Unencumbered by Crawfurd's commitment to fundamental racial difference, Earl could allow for mixture, though any such mixture necessarily proceeded from an assumption about the existence of pure types from which mixtures were produced. Diametrically opposed to Crawfurd on the significance of variation amongst Oriental Negroes, for Earl 'all the Negro tribes to the eastward of the continent of Asia, belong to one and the same race'.[72]

Not surprisingly, Wallace's approach to questions of race and the origins of human difference was altogether more systematic than those of Crawfurd and Earl. Wallace appears to have selected the Malay Archipelago as a field site precisely because he regarded it as a possible point of origin for human beings; as the seat, according to the then anonymous author of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), of both the 'least perfectly developed' human types, the Negro and the Malay, and 'the highest species of the quadrumana'.[73] Contrary to Crawfurd's taste for a proliferation of racial categories, Wallace's avowed preference — like Cuvier's — was for just:

three great races or divisions of mankind … the black, the brown, and the white, or the Negro, Mongolian, and Caucasian. If we once begin to subdivide beyond these primary divisions, there is no possibility of agreement, and we pass insensibly from the five races of Pritchard [sic] to the fifty or sixty of some modern ethnologists.[74]

Somewhere in the Malay Archipelago, he reasoned, lay the faultline between two of these three 'great races'.

Wallace approached Gilolo fully anticipating that his observations on its indigenous inhabitants would equip him with the material necessary to challenge the prevailing thesis that Papuans were related to and most probably derived from Malays, as two 'classes' of a great Oceanic race; a thesis which was subscribed to by leading monogenist authors such as Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), Prichard, and his successor Latham. For these men, 'transitional' or 'intermediate' forms between adjacent races served as the guarantee for the essential unity of the human race. Latham (1850:211-2), citing Crawfurd, had even specified that a search of the 'parts about Gilolo' would yield evidence for the source of the Papuans in the form of a population 'intermediate' between the Papuan and Malay forms. As Wallace wrote later (1880a:529): 'If these two great races were direct modifications, the one of the other, we should expect to find in the intervening region some homogeneous indigenous race presenting intermediate characters'. In terms of Wallace's developing thesis of distinctly evolved zoological and anthropological domains, it was essential that the population of Gilolo mark a sharp break between Papuan and Malay. Once there, he was 'soon satisfied by the first half dozen I saw that they were of genuine papuan race' with features 'as palpably unmalay as those of the European or the negro'.[75]

John Langdon Brooks (1984:183-4) speculated that Wallace was seeking evidence for the dying out of intermediate forms between the Malay and Papuan in order to demonstrate the ultimate derivation of Papuan forms from an original Malay. Wallace was certainly not entirely averse to the notion of intermediate forms, invoking them to account for the great variety in his Polynesian or Great Oceanic race (1865:212). However, a more plausible explanation is that Wallace's real goal was to establish the antiquity of man more generally by linking Papuans to African Negroes as related members of the great 'Negro' race.[76] The separation of these two Negro populations by the emergence in situ of Malays of the great 'Mongolian' race would then demand a hitherto unsuspected temporal depth for human evolution (1880a:593): 'if these two races [Malay and Papuan] ever had a common origin, it could only have been at a period far more remote than any which has yet been assigned to the antiquity of the human race'. Even where Wallace (1880a:592) allowed for 'mongrelism', in canvassing the possibility that the Polynesians represented an 'intermingling' of Malay and Papuan, he insisted that this must have taken place 'at such a remote epoch, and … so assisted by the continued influence of physical conditions, that it has become a fixed and stable race'. For Wallace, 'the racial differences were primitive. Malays and Papuans hailed from separate continents, like the other fauna in the archipelago. There could be no true "transitional" forms'.[77]

The problem of 'admixture' remained, however, for Wallace's Papuans at Gilolo were evidently not those of New Guinea:

They are scarcely darker than dark Malays & even lighter than most of the coast malays who have some mixture of papuan blood. Neither is their hair frizzly or wooly, but merely crisp or waved … which is very different from the smooth & glossy though coarse tresses, every where found in the unmixed malayan race.[78]

Here, Wallace oscillated between a verdict of relatively recent 'admixture' between Malay and Papuan, congruent with his suggestion that Malays had overrun the natural boundary between the two, and occasional acknowledgement of a possible third, intermediate race which he identified tentatively as 'Alfuru' or 'Alfuro'.[79] In his commitment to the simplicity of a single line dividing just two races, Wallace had elected to ignore the implications of the unevenness of his zoological line and the possibility that the area he assigned to this third race corresponded to the transitional zone between his line and the line to the east later identified by Richard Lydekker (1849-1915).[80]

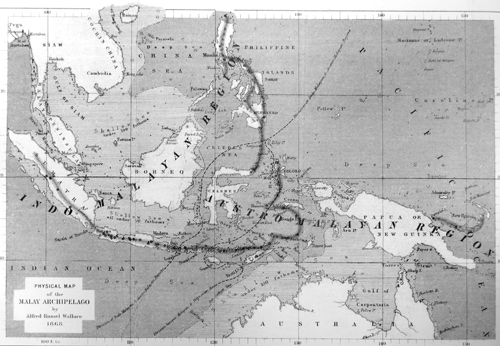

Wallace's insistence on extending the contrast between Malay and Papuan eastwards into the Pacific would ultimately bring his ethnological scheme undone. The primacy that he accorded to the correspondence between zoological and human distributions led Wallace to identify all people east of the line, including Polynesians, as variations on a Papuan theme; indeed, his ethnological line is captioned 'Division between Malayan & Polynesian Races' (Figure 16). In this opinion, Wallace ran sharply counter to the established positions of scholars such as the naturalist and surgeon George Bennett (1804-1893) and Marsden who insisted on the closeness of linguistic, moral, and physical connections between Malays and Polynesians.[81] In order to assert 'the close affinity of the Papuan and Polynesian races, and the radical distinctness of both from the Malay', Wallace toyed initially with geological catastrophism or extensionism.[82] Rejecting the evidence of similarity between Malay and Polynesian vocabularies established and published by Marsden (which he ascribed to recent borrowings) and the oral traditions of Polynesian migration (deemed impossible against the prevailing winds), Wallace sought to bring Polynesians and Papuans together 'as varying forms of one great Oceanic or Polynesian race'.[83] This variation, Wallace argued, could be accounted for by an 'hypothesis … which does not outrage nature, as does that of the recent derivation of the Polynesians from the Malays'; namely, that massive and ancient subsidence across the Pacific had stranded small islands of ancestral Papuans and Polynesians on isolated volcanic peaks and that, 'while man and birds were able to migrate to these, the mammalia dwindled away and finally perished, when the last mountain-top of the old Pacific sank beneath the Ocean'. So much, it would seem, for field observation.

Engraving. Photograph B. Douglas.

[67] Crawfurd's deference to the experience of the French voyagers was not entirely reciprocated, at least by the pharmacist-naturalist René-Primevère Lesson (1794-1849), who dismissed Crawfurd's denial of physical analogies between Papuans and Madagascan Negroes as 'in this case, unsupported by any positive evidence' (1829:202, note 4).

[68] Crawfurd 1856:249-53, 294-7.

[69] Crawfurd here appeared to privilege 'observation' but rather hid behind it, for nowhere did he explain how one might observe 'admixture in progress'. Only in Fiji did he allow for some 'admixture' between Oceanic Negroes and Polynesians (1865a:114).

[70] Crawfurd 1861b:169; 1865a:117.

[71] See Chapter One (Douglas), this volume, for an outline of the tangled logic and emotions of mid-nineteenth-century scientific discourses on racial mixing that formed the broader context for Crawfurd's almost neurotic aversion to the 'commixture of races'.

[72] Earl 1849-50:1, 3, 6, 9, 68, 69-70.

[73] Chambers 1994:296, 308; Moore 1997:298.

[74] Wallace 1905, II:128. See Chapters One and Two (Douglas), this volume, on Cuvier's influential general division of humanity into three major races, 'Caucasic', 'Mongolic', and 'Ethiopic'.

[75] Wallace [1856-61]: entry 127, original emphasis.

[76] Wallace (1864) had already made the case for a greater antiquity for human evolution in the form of an address to the Anthropological Society of London in which he argued that physical differences represented a very early adaptation to different environments and modification from a single homogenous race, after which rapid moral and mental development endowed the different races with varying aptitudes and corresponding historical fates.

[77] Moore 1997:305, fn.10. Hence Wallace's oft-quoted prescription: 'no man can be a good ethnologist who does not travel, and not travel merely, but reside, as I do, months and years with each race, becoming well acquainted with their average physiognomy and their character, so as to be able to detect cross-breeds, which totally mislead a hasty traveller, who thinks they are transitions' (Wallace to George Silk, [1858], in Wallace 1905, I:366, original emphasis).

[78] Wallace [1856-61]: entry 127.

[79] Wallace 1865:207-8; 1880a:588.

[80] Clode and O'Brien 2001:118-19.

[81] Bennett 1832; Marsden 1834.

[82] Wallace 1865:212; 1880a:593. Fichman (1977; 2004:51-3) traces Wallace's gradual rejection of extensionism during the late 1860s and 1870s.

[83] Wallace 1991:47. Wallace was fairly swiftly and heavily criticized for his views on Polynesians by his peers, such as Meinicke (1871), as well as by missionaries who did have the requisite field experience in the region, such as George Brown (1835-1917) and Samuel James Whitmee (1838–1925) (Brown 1887; Whitmee 1873).

[84] Wallace 1880a: following 8.