Péron's proposed socio-physical hierarchy was explicitly racial but the relatively limited geographical span of his voyage made regional racial classification largely irrelevant to his narrative. Indeed — except with respect to New Holland and Van Diemen's Land where Europeans were ensconced after 1788 and 1803, respectively, and Tahiti where missionaries settled in 1797 — the knowledge base readily available for such an enterprise did not grow significantly between Cook's last voyage and the resumption of scientific voyaging by France in 1817 after the long hiatus of Empire and war. Cuvier's (1817a, I:94-100) brief catalogue of the 'varieties of the human species', published that year, was both exiguous and indecisive about the 'handsome' Malays, who included the South Sea Islanders, and the 'frizzy-haired', 'black', 'negroid', 'extremely barbarous' Papous. He complained of insufficient information to identify either with one of his three great races but thought the Papous might be 'negroes who had long ago strayed across the Indian Ocean'.

Péron's successors as naturalists on the French Restoration voyages were all serving naval officers, in keeping with a new policy instituted from 1817 to circumvent the conflicts with civilian scientific personnel that had plagued Baudin's voyage. Henceforth, only naval medical officers instructed in natural history would be formally appointed as naturalists on scientific voyages though other officers also contributed, most notably Dumont d'Urville.[77] Several turned their hand to regional taxonomy of the human populations they had encountered, observed, and studied. The shifts and ambiguities in voyage naturalists' representations and classifications of indigenous Oceanian people after 1817 provide another index of congealing racial presumptions in the science of man. However, the influx of new empirical knowledge only complicated the difficulties of trying to match received theoretical systems with fleeting observations of baffling human variation or ambiguous affinities and the ambivalent experience of unpredictable local behaviour.

The first of the new breed of professional surgeon-naturalists were Quoy and Gaimard who served with Freycinet on the Uranie in 1817-20.[78] They co-produced the official Zoologie volume and plates of the voyage (1824a, 1824b), though Quoy seems to have drafted much of the text. Only eleven of 712 pages and two of 96 plates were devoted to 'Man', in the shape of a brief scientific paper on the 'physical constitution of the Papous'.[79] The authors' primary concern for the skull as 'the bony envelope' for the organs of intelligence recalls Cuvier's earlier instructions to Péron. Though descriptive rather than taxonomic, the paper reveals the uneasy liaison of an a priori racial system and recalcitrant facts. Papou was a vexed and ambiguous category.[80] From the early sixteenth century, Portuguese and Spaniards had extended the local toponym Papua to refer to the 'black' inhabitants of the 'Papuan Islands' and the nearby New Guinea mainland (now in Indonesia); Blumenbach and Cuvier 'generalized' Papus/Papous to denominate 'black' Oceanian people collectively; so did Freycinet, Quoy and Gaimard's commander.[81] But the naturalists themselves limited Papou to certain people they had seen in Waigeo and neighbouring islands and sharpened the term's racial import by differentiating them from the similarly coloured 'race' inhabiting New Guinea itself, said to be 'true Negroes'. The Papous posed a racial conundrum for Quoy and Gaimard who could not work out their 'distinctive characters'. They reasoned that racial 'mixing' in a dense cluster of islands must have produced such a 'multitude of nuances' that it was hard to determine the components: in physiognomy and hair, the Papous seemed 'to occupy the middle ground' between Malays and Negroes; their skull form was close to the Malays; and their facial angle corresponded to that of Europeans.[82]

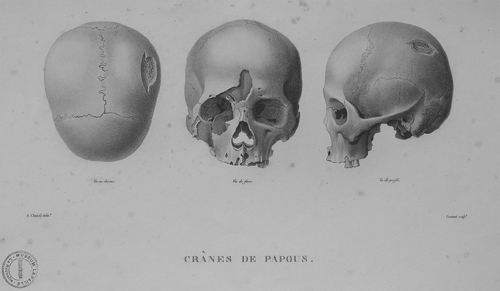

Two engraved plates of skulls of Papous plundered from indigenous graves illustrate Quoy and Gaimard's text (Figure 7). They had submitted them 'for examination' to the German physiologist Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), founder of the science of the cerebral localization of mental faculties known as phrenology. Gall's influence on Quoy and Gaimard's paper clearly outstripped that of their patron Cuvier, a professional enemy of Gall, and drew a sceptical response from the editors of the Nouvelles annales des voyages — one of whom was Malte-Brun — which published the earliest version of the paper in 1823.[83] The authors' confident summary of the 'moral and intellectual faculties' of the Papous shows how readily phrenological terminology could slide into conventional racial essentialism (1824c:9-11): they had innate 'dispositions to theft'; a 'destructive instinct' so strong as to produce a 'penchant for murder' and the presumption of cannibalism; and a 'tendency to superstition'. Yet the paper's optimistic conclusion — entirely missing from the first published version — is a paradoxical reminder that phrenology could offer a radical technology for personal and racial improvement:[84] the Papous were 'wrongly considered by clever naturalists to be close to the Apes';[85] they were 'capable of education'; and they only needed 'to exercise and develop their intellectual faculties in order to hold a distinguished rank among the numerous varieties of the human species'.

Engraving. Photograph B. Douglas.

The racial taxonomy of Oceania gained new momentum from the early 1820s when the recently formed Société de Géographie in Paris offered one of its annual prizes for a memoir on the 'differences and similarities' between the 'various peoples' of the region. Garnot, Lesson, and Dumont d'Urville, who had ranged widely across Oceania with Duperrey on the voyage of the Coquille (1822‑25),[87] all tackled the theme following their return to France but it seems that no entry was actually considered and the prize eventually lapsed in 1830 without award.[88] These works were self-consciously enunciated in the discourse of an emerging professional science of race by men whose primary vocation was medical, or naval, or both, but who aspired to convert their empirical authority into scientific credibility by reading papers to scientific societies and publishing in their journals (Staum 2003). Like Malte-Brun and following Cuvier, all three men used the term race in a modernist biological sense. Their racial pronouncements were at best patronizing, partial, and essentialist and at worst scurrilous. The physicalism and racialism of their scientific agenda are patent in Lesson's (1826:110) published advice to his younger brother — about to sail for Oceania as Dumont d'Urville's assistant surgeon — to try to advance Cuvier's 'wise works in comparative anatomy' by procuring indigenous skeletons: their 'very characteristic facial type' would enable anatomists to draw 'new conclusions from skeletal structure in order to throw light on the races'.

Garnot's first effort (1826-30) was a global classification of 'the human races' along 'simple' Cuvierian lines. In the process, he differentiated an 'Oceanic branch' of the 'yellow race', occupying most of the South Sea Islands, from a generalized Papou branch of the 'black race' located in the western Pacific Islands, New Guinea, Van Diemen's Land, and New Holland. The 'Oceanians' were typified in the 'well-built' Tahitians whose facial angle was 'as open as that of the Europeans'; the Papous were 'in a way a hybrid variety' characterized by a much more oblique facial angle than Tahitians; those inhabiting New Holland had an even narrower facial angle and were 'without doubt the most hideous peoples known'.[89] An expanded version of the memoir published in a dictionary of natural history concludes with six engraved plates, four of which deploy images of Oceanian people to typify the 'Mongolic' and 'Ethiopic' races.[90] In a companion piece on the 'Negro', focussing on 'the Negro of New Holland', Garnot (1837:628-30) abandoned the term Papou and reconstituted the 'black race' of Oceania as a 'frightful'-looking branch of the 'Negro race'. A 'very different' physical organization 'from ours' meant that Negroes in general were 'inferior' to the 'yellow and white races' while some were 'uncivilizable' — notably in New South Wales where their organization was 'closest to the Baboons'.

The pharmacist Lesson, who became chief surgeon when Garnot was forced by illness to quit the voyage at Port Jackson, published a far more elaborate regional racial classification.[91] In contrast to Garnot's broad brush, Lesson proposed a convoluted schema that lauded the 'Hindu-Caucasic' Oceanians (modern Polynesians) as 'superior' to all other South Sea Islanders in 'beauty' and bodily conformation and split the 'black race' into two branches distributed between four varieties: the Papouas or modern Melanesians; the 'Tasmanians' of Van Diemen's Land; the Endamênes of the interior of New Guinea and some large Malay islands; and, at the base of the hierarchy, the 'Australians' of New Holland. He represented all 'these negroes' as intellectually and morally deficient but the 'austral Negroes' of New Holland — whom he had only seen demoralized by disease, expropriation, and alcohol in colonized areas around Port Jackson — as sunk in especially 'profound ignorance, great misery, and a sort of moral brutalization'.[92]

In Lesson's work, as in Quoy and Gaimard's, the anomalous appearance and conformation of certain so-called Papous confounded a presumptive racial system and induced tortuous logic and muddled rhetoric. In his contemporary shipboard journal, Lesson confidently assigned 'the natives' of Buka, north of Bougainville, to the 'race of the Papous' on the basis of the 'characteristic' small facial features and bouffant hairstyles of six men fleetingly encountered at sea (Figure 8). In nearby New Ireland, where the vessel anchored for ten days, he described meeting a 'negro race' with 'woolly' hair worn in braids who closely resembled the Africans of Guinea but 'differ much' from their Papou 'neighbours' in Buka (Figure 9).[93] He restated the case for radical difference in a letter sent from Port Jackson to the editor of an official publication (1825:326): the New Irelanders were of 'negro race' and in physical constitution 'quite opposite' to the Papous.

Pen and wash drawing. SH 356. Vincennes, France: Service historique de la Défense, département Marine. Photograph B. Douglas.

Pen and wash drawing. SH 356. Vincennes, France: Service historique de la Défense, département Marine. Photograph B. Douglas.

Yet Lesson evidently thought better of his initial impression since, in his journal, the phrase 'differ much' is crossed out and replaced with 'differ little'.[96] The confusion is compounded in his formal racial taxonomy by shifts between narrow and more generalized meanings of the term Papous/Papouas (1829:200-7): between Quoy and Gaimard's specialized sense of 'Negro-Malay' hybrids living on the 'frontiers' of the Malay islands and along the northwest coast of New Guinea; and a broader signification to designate 'negroes' inhabiting the New Guinea littoral and the island groups as far east as Fiji — that is, the modern Island Melanesians. Eventually, in a belatedly published narrative of the voyage (1839, II:13, 35, 56), Lesson conflated the once 'opposite' Bukans and New Irelanders as 'Papouas', 'negroes', or 'Papoua negroes'. Yet this usage was less inclusive than Cuvier's and Garnot's blanket labelling of all 'black' Oceanians as Papous since Lesson (1829:200-25) consistently differentiated Papouas from the 'negro' Alfourous or Endamênes supposedly 'aboriginal' to inland New Guinea and to New Holland.

Dumont d'Urville's journal (1822-5) of his voyage as first lieutenant of the Coquille remains unpublished but in the year before he left again for Oceania in 1826, in command of the Astrolabe, he wrote an unfinished manuscript ([1826]) addressing the essay prize questions. In the process, he split the inhabitants of Oceania into 'three great divisions which seem the most natural': first, 'Australians', 'Blacks', or 'Melanians' ('from the dark colour of their skin');[97] second, 'peoples of Tonga', the 'true Polynesians', 'adherents of taboo'; and third, 'Carolines'. The 'Malay race properly speaking' at this stage remained outside the classification but the manuscript anticipated in all but names Dumont d'Urville's classic tripartition of Pacific Islanders into Melanesians, Polynesians, and Micronesians.

Quoy and Gaimard served as naturalists on Dumont d'Urville's expedition which crisscrossed western Oceania in 1826-29 and they again co-produced the Zoologie section (1830-4) of the official voyage publication.[98] Quoy began this work with a short treatise locating man in Oceania 'in his zoological relationships' as first among mammals.[99] Explicitly taxonomic, he lauded Forster's 'natural' divisions of Oceanian people but reconfigured them as 'two pronounced types', 'the black race and the yellow race'. For Quoy, as for Cuvier and most contemporary naturalists, the primary races were ontologically real and 'very distinct': the differences between them were innate and based in physical organization whereas the differences between the varieties of those races were 'only nuances' produced by external 'modifiers' such as climate, soil, and 'habits'. Since the 'two principal types' of Oceanian people were unmistakable, the anthropological task of the anatomically trained naturalist was to 'grasp the varieties'.[100] Accordingly, Quoy devoted the bulk of his chapter 'On Man' to differentiating each race into the varieties known personally to him and Gaimard.[101] This empirical section incorporates long extracts from Quoy's shipboard journal, producing marked tension in the text between his deductive system and circumstantial anecdotes: between a reductive, purportedly objective, but fundamentally racialized theoretical schema and contingent details about the haphazard, idiosyncratic behaviour and appearance of actual human beings.[102]

Though mainly concerned to catalogue the 'physical characters' distinguishing the admired 'yellow race' (the future Polynesians and Micronesians) from the vilified 'blacks' (the future Melanesians and Australians), Quoy discerned 'no less fundamental distinctions' in 'morals' and 'habits'. He dichotomized responses to Europeans in what would become enduring racial stereotypes: the yellow race welcomed voyagers with trade and women whereas the blacks were isolated, warlike, suspicious, and 'excessively jealous of their women'. These 'defining characters' ensured that one race, with European help, would take 'great strides towards civilization' while the other, 'refusing all contact', would 'stagnate'.[103] In manuscript notes for his chapter (n.d.a), Quoy drew an explicit, Cuvierian causal linkage between the physical and the moral by attributing intellect and morality to biology: the 'progress' of the 'negro race', he maintained, was thwarted by an 'obstacle in its organization' which ensured its 'inferiority' and could only be overcome by racial crossing. This grim prognosis is at odds with the catholic optimism of Quoy and Gaimard's earlier text (1824c:2, 11) which allows the Papous the capacity for intellectual advance; attributes the 'miserable' condition of people seen at Shark Bay in western New Holland to 'a soil of the most frightful poverty' which had stymied their 'development and perfection'; and asserts their common humanity, since their 'state' was 'still far' from brutish. In dramatic contrast, Quoy's later chapter represents the New Hollanders as barely human — 'a very distinct and one of the most degraded' varieties of the black race — and as possibly a separate species.[104] This shift in tone and outlook between the 1824 and 1830 texts attests both to a hardening in learned European opinion on human differences in the interval between the voyages and to the authors' more intense and fraught experience of indigenous behaviour on the second.

In 1832, Quoy's commander Dumont d'Urville published a seminal paper synthesizing a quadripartite regional geography and a dual racial classification from the works of his predecessors and his own wide-ranging travels.[105] Spatially, he divided Oceania into four 'principal divisions': Polynesia, Micronesia, Malaysia, and Melanesia. Like Quoy, Dumont d'Urville claimed to be heir to the 'simple and lucid system of the immortal Forster' but appropriated it to serve a starkly racialized anthropology. He reconfigured Forster's labile varieties into two 'truly distinct races': a 'copper-coloured' race of 'conquerors' had come from the west to destroy, expel, or co-exist and intermix with a 'black race' who were 'the true natives' or at least the first occupants of the region. He distributed the copper-coloured race between 'Polynesians' and 'Micronesians'; replaced Melanian with the neologism 'Melanesian' to name 'the black Oceanian race'; and consigned the 'Australians' and the 'Tasmanians' to the 'last degree' of his human hierarchy as 'the primitive and natural state of the Melanesian race' which was 'only a branch of the black race of Africa'. He adjudged Melanesians to be 'hideous' in appearance, 'limited' in languages and institutions, and 'generally very inferior' to the copper-coloured race in dispositions and intelligence, except where they had been improved by frequent communications and racial intermixture with Polynesians, as in Fiji. But he saved his most persistent obloquy for the Australians and Tasmanians who were 'probably the most limited, the most stupid of all beings and those essentially closest to the unreasoning brute'.[106] Not only did Dumont d'Urville (1832:15-20) reinscribe the conjectural narrative of ancient racial migration and displacement proposed by Brosses and Forster but, like Quoy, he reworked it as modern history and colonial necessity: 'organic differences' in the 'intellectual faculties' of races determined a 'law of nature' that the black 'must obey' the others or 'disappear' while the white 'must dominate'.

Dumont d'Urville's racial taxonomy was more concise and economical than his colleagues' long-winded efforts but actual human idiosyncrasy and diversity threatened the integrity of his categories and challenged his racial preconceptions. Again (1832:17-18), the Papous were notable culprits. Like Quoy and Gaimard, he confined them to 'a very small part' of the coasts of west New Guinea and neighbouring islands which he had personally visited and distinguished them from the 'true Melanesians' populating most of New Guinea and the island groups to the east. However, he postulated migration rather than hybridity to solve the mystery of the Papous' affinities and origins: they might be just 'a handsome variety of the Melanesian race' but more likely were relatively 'recent' arrivals from as far afield as Madagascar. A candid passage reveals the aesthetic and discursive power of racial stereotypes, particularly the disagreeable spectre of the Negro and its Oceanic metonym. In Celebes (now Sulawesi in Indonesia), Dumont d'Urville heard that the inhabitants of the interior were Alfourous, a term which 'instantly' brought to mind the blackness, 'frizzy hair', and 'flat nose' of the 'true Melanesians'. 'Astonished' when they turned out in the flesh to resemble figures he had seen in Tahiti, Tonga, and New Zealand, he duly installed Celebes as a likely 'cradle' of the Polynesian race.

Despite such anomalies, Dumont d'Urville's elegant racial classification of Oceania ultimately prevailed and became, with minor modifications, the standard international terminology. Eventually, shorn of his brutally negative caricature of Melanesians — though not of its racial connotations — it was naturalized in modern indigenous usages by Pacific Islanders themselves.

[77] Cuvier 1825:177-82; Hamy 1906:457; Ollivier 1988:45-50; Quoy and Gaimard 1824a:[i]; Staum 2003:105-17.

[78] The Uranie visited New Holland, Timor, Waigeo, the Marianas, the Carolines, and Hawai'i.

[79] Quoy and Gaimard 1824b: plates 1, 2; 1824c. The paper was originally read to the Académie des Sciences on 5 May 1823; a long 'extract' attributed to Gaimard was published in the Nouvelles annales des voyages (1823); a somewhat different version appeared as the chapter 'On Man' in the Zoologie volume of the Voyage (1824c) and was republished with a few changes of wording in the Annales des sciences naturelles (1826).

[80] See Chapter Three (Ballard), this volume.

[81] Blumenbach 1806:72; Cuvier 1817a:99; Freycinet 1825-39, I:521-2, 589-90; Gelpke 1993:326-30.

[82] Quoy and Gaimard 1824c:3-6.

[83] [Quoy and] Gaimard 1823:121-6. The later versions of the paper (1824c:7; 1826:33) refer to Gall as 'this celebrated physiologist' but in 1823 he is 'this ideologue doctor' — perhaps an editorial embellishment. Cuvier was a bitter critic of Gall's 'materialist' conception of the mind-brain relationship and dismissed phrenology as a 'pseudo-science' (Gall and Spurzheim 1809; Rudwick 1997:87).

[84] Quoy and Gaimard 1824c:11; 1826:38; cf. 1823:126. See also Renneville 2000:83-96; Staum 2003:49-52.

[85] This clause appears only in the final version of the text (1826:38).

[86] 'Papuan skulls' (Quoy and Gaimard 1824b: plate 2).

[87] The Coquille visited Tahiti, Borabora, New Ireland, Waigeo, the Moluccas, Port Jackson, New Zealand, the Carolines, west New Guinea, and Java.

[88] Anon. 1825:215; 1830:174.

[89] Garnot 1826-30:509, 511-15, 518-20. This work was published in Lesson and Garnot's two-volume Zoologie of the voyage of the Coquille (1826-30) and subsequently expanded into an entry on 'Man' in the Dictionnaire pittoresque d'histoire naturelle (1836).

[90] Garnot 1836: plates 218-21.

[91] Lesson was a prolific, if repetitive publisher, prompting Quoy (1864-8:140), his senior naval medical officer and sometime patron, to lament his 'too great facility for writing'. Lesson's racial classification cobbled together several mémoires that had been read as scientific papers to the Société d'Histoire naturelle in Paris during 1825 and 1826 under his and Garnot's names. The composite paper was first published in Lesson and Garnot's Zoologie (1826-30, I:31-116) but Lesson claimed sole authorship of all but the final section and republished it as an appendix to his Voyage médical (1829) — the version cited here.

[92] Lesson 1829:157, 164, 168, 203-4, 214, 219. In a footnote (1829:220, note 1), Lesson insisted that his use of the term 'negro' was purely descriptive, referred only to skin colour, and implied no 'analogy' between black Africans and Oceanians (unlike Garnot's usage).

[93] Lesson 1823-4, II:275, 310, 313.

[94] 'Papou of Bougainville Bouca Island' (Le Jeune [1822-5]: folio 74).

[95] 'New Ireland' (Le Jeune [1822‑5]: folio 20).

[96] Lesson 1823–4, II: 310, my emphasis.

[97] Dumont d'Urville borrowed the term Mélanien from the French soldier-biologist Jean-Baptiste-Geneviève-Marcellin Bory de Saint-Vincent (1778-1846) who applied it to the fourteenth and 'penultimate' species in his polygenist classification of the human genus (1827, I:82; II, 104-13).

[98] The Zoologie of the voyage of the Astrolabe in 1826-29 comprises four large volumes and a superb Atlas of 198 engraved plates (Quoy and Gaimard 1833). The expedition visited New Holland, New Zealand, Tongatapu, Fiji, New Ireland, northern New Guinea, the Moluccas, Van Diemen's Land, Vanikoro, Guam, and the Malay Archipelago.

[99] Quoy and Gaimard 1830:18. A manuscript draft of this chapter in Quoy's handwriting is held by the municipal Médiathèque in La Rochelle, France (Quoy n.d.a).

[100] Quoy and Gaimard 1830:16-17, 50-3, original emphasis; see also Cuvier 1817a, I:18-19.

[101] Quoy and Gaimard 1830:18-46.

[102] E.g., Douglas 1999a:86‑7; 1999b:182-9.

[103] Quoy and Gaimard 1830:46-9.

[104] Quoy and Gaimard 1830:29, 40; see below.

[105] The published paper, 'On the Islands of the Great Ocean', is dated 'Paris, 27 December 1831' but was read to the Société de Géographie on 5 January 1832 and appeared in the 1832 volume of its Bulletin.

[106] Dumont d'Urville 1832:2‑6, 11‑15, 18-19.

![Figure 8: Jules-Louis Le Jeune, 'Papou de L'Ile Bougainville Bouca' [1823].'Papou of Bougainville Bouca Island' (Le Jeune [1822-5]: folio 74).](../images/fig08.jpg)

![Figure 9: Jules-Louis Le Jeune, 'nelle Irlande' [1823].'New Ireland' (Le Jeune [1822‑5]: folio 20).](../images/fig09.jpg)